It is hard to describe, even for a writer, what a heaven the Sewanee Writers’ Conference is for a literary geek like me: craft talks in the mornings, writing workshops in the afternoons, and readings every evening; sharing meals with your favorite icons of literature during the day, and drinking with them at night; and spending the entirety of this time in an idyllic setting of flagstone courtyards and shady oaks, complete with wandering fawns. It was near the end of this two-week spiritual retreat when we were reminded that poet Andrew Hudgins would deliver a craft lecture that afternoon. I write fiction for the most part, but I am a sort of poetry groupie, as my students are fond of reminding me. When I read a poem for class, no matter how many times I’ve delivered those same lines, I am still able to get teary eyed and lose my voice, an emotional knot forming in my throat when a familiar but favorite image forms in my head. Yet in spite of my appreciation for the art, I don’t usually write poetry. And on occasion I feel uncomfortable teaching it, its complexities of craft still something of a mystery.

Yet here at Sewanee everyone mingled with everyone else—poets with playwrights with fiction writers, famous and not, published and not, emerging or well established. It didn’t matter. You could sit in on Mark Strand’s workshop without even having to ask permission. You just showed up, and there it was, your front row seat to the mind of a poet laureate, and it didn’t even cost you an extra effort in a bouquet of proffered apologies.

Poets and prosers mingle at Sewanee / photo by Will Coley

Therefore, when it was Hudgins’ turn to give a craft lecture, I was one of the first to go, eager to absorb what I could smuggle back to those students in my undergraduate workshop who had more of an ear for poetry than me, their fiction-writing professor. I needed to be at that lecture for professional obligations; I wanted to be there for personal desires. But just as I was beginning to reach towards the trellises of poetic symmetry, grasping for that hanging fruit, I heard Hudgins say, a mocking lilt to his voice, “…and then he became a fiction writer, like all failed poets tend to do.”

I straightened in my chair and looked around the two dozen plus attendees present at that lecture. Many were scholarship recipients and fellows, like me, but I was the only fiction writer in the room, and the only one not to laugh with that wink-wink, nudge-nudge that was spreading with coy smiles from face to face. A curious sense of inferiority prevailed, and I got up, quietly, stuffing my notebook under my arm, tiptoeing out of the lecture hall. Hudgins’ joke, harmless as it was, struck a raw place inside me. What was I doing, anyway, at a writers’ conference that was crawling with some of the most acclaimed prose writers of our decade, spending my limited time in a poetry lecture? Just who did I think I was, deluding myself that I could pass myself off as a poet?

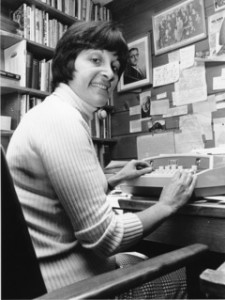

Maxine Kumin (AP Photo)

Back in 2001, when I did my first MFA program at Florida International University, professors shoveled poetry at us fiction writers like it was dirt for a six-foot ditch: it was a requirement of the graduate program that all students, regardless of their specialty, had to take at least one graduate workshop in the genres of fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry. That’s how in my third semester I found myself facing the pointed outrage of formalist Maxine Kumin, whose visiting lectureship had not specified her having to teach, in the same workshop, not only poets, but also several fiction writers who had never even taken an undergraduate poetry workshop before. We frightened three huddled together desk-edge to desk-edge on the right side of the class, eschewing direct visual contact. “It’s like teaching two different courses,” exclaimed the poet laureate, eyeing us fiction writers like a farmer eyes an infected plant. We were certain that her intentions were to eradicate us from the class like so much weed, spraying us with toxic complex syntax structures required of assignments, which, in addition to everything, had to have an exact syllabic count and a rhyme scheme. Somehow we survived through the series of ghazals, sonnets, pantoums, and other exotic sundries of the literary stem, plucking the thorns of meter and line breaks from our bruised attempts at prosody, managing through the course with many apologies to our much superior colleagues and offering them the fruits of our labor—not the preservation of the world’s beauty by capturing its delicacy, but literally “preserving” it like so much jam. These trembling, gelatinous creations we produced by mashing, processing, sterilizing, and canning our mistaken preconceptions of what good poetry should be. We wrote like fictioneers write poetry: attempting to overcome with syrupy descriptions the few insipid banalities we managed to detangle from the prickly brambles of form.

Simultaneous to that experience I took the only form course available that semester, an overview of poetry forms taught by Genius Award recipient Campbell McGrath. If Kumin was plowing and tilling us with form, McGrath was floating us into the deep, high currents of language poetry, abandoning us in those places where sky and water become indistinguishable. I was nostalgic for the solid, rocky coastline of fiction, towards which I paddled during my breaks after fishing a few lines of passable prosody. When after these two classes I presented my mossy prose to my mentor, fiction writer John Dufresne, the results were painful and predictable.

The story I had written was inspired after Louise Glück’s Wild Iris, a collection of poems addressed to flowers wherein the flowers stand in as symbols for poetry itself. I had written my story in first person, and, like Glück, I had attempted to make my narrator address a triple-audience: the reader, fiction writing, and a character in the story—a reluctant lover unwilling to commit or to give up his illicit affair. I was seduced by Glück’s sub textures, the multiple meanings embedded in the lyrical metaphors, the ambiguous nature of the voice and its subject matter. But instead of creating the multi-dimensionality I’d hoped for, my work was simply confusing. Worse, it came across as overly clever.

Dufresne, rightly, was having none of it. He failed to see the elevated double-entendre of the image, and found the idea of two adults making love while a child waits alone in another room distasteful. It was bad, I admit it, the low point of my fiction career. “They’re killing me with poetry,” I cried out after Dufresne finalized his disappointment by flapping the pages in the air and hitting them with the back of his hand, which hurt more than the worst of his verbal criticism. “That should be the title for a short story,” was his appeasing rebuttal, but he was obviously eager to move on. I wanted to explain that poetry was exercising a part of my brain that up to that point could barely hold up a cup of tea—the weak muscles of conceit, rhyme, and invention had atrophied by the over-use of psychological character analysis in fiction—but there was no sympathy to be had. Yes, I had allowed myself to be overtaken by “idea” and lost sight of “story.” But wasn’t there a way to bring poetics to prose? Or is it only the rare individual—Joyce, Ondaatje—who can travel in both worlds?

What I begrudgingly accepted that semester was that forms don’t mix so easily – at least, not for me. I see this in my students all the time: those who do well in prose can do no better than some chopped prose for poetry, and those who wrote clichéd TV re-runs for fiction come alive when they suddenly have to tangle in only a few lines with the complexities of living. With some exceptions, even the professional world reflects this discrepancy: poets will write novels in verse, while fiction writers will write prose poems. (“Add some line breaks!” Campbell would dare us, his edgy tone of voice suggesting we were cowards. “What’s wrong with line breaks? Don’t give me that prose poem stuff; that’s a copout.”) I began to suspect that if fiction and poetry were people, they’d be like a Jew and a Muslim: they may have some things in common, but nobody would ever seat them together at a wedding; nobody would expect them to do anything but argue.

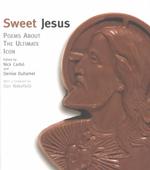

If my prose mentors were unsympathetic, my poetry peers were cryptic: “There is no one way to write a poem,” my friends laconically advised, even in Kumin’s formalist class, where syllabic count, repetition, rhyme and form all appeared to have preset, unchangeable constructs. The structures and rhyme schemes I could recognize easily enough: but it was the images inside the lines that felt ethereal. Poem after poem, I would try to say something useful to my fellow poets, to uncover some code that would crack open the mystery of poetry to me, and that would help me, when I sat down to compose my assignments, identify patterns that would gauge where I was in the poet-growth process. But it was not to be. “Poetry is just poetry,” is what I kept being told; “It’s like asking what makes art.” I kept on seeing this mystery repeated in the wild patterns of my friends’ publication, a golden ratio of success that was as intriguing as the exact geometric patterns of seashells. “A poem could be a joke,” my friend Mark M. Martin apologetically explained in reference to a poem titled “Jesus Plays Super Sega” that he’d managed to publish in an anthology edited by Denise Duhamel. In Martin’s poem, the narrator is shocked by the miraculous presence of Jesus in his living room playing games on his computer, but he cannot get a response from the Messiah beyond a terse “Wait a minute.” Mark could not explain what made his poem publishable other than the fact that it was funny, but the funny thing was that I sort of “got” the poem in the joke. I could see Jesus’ intensity, could feel the Messiah’s bristling frustration at the needy interruption of the narrator… It was an image that revealed something beyond what it said. I could not have explained it then, but I was learning to sense the poem like a kōan, beyond its logic and literal value.

Still, I kept seeking to solve the kōan as if it were a Rubic’s cube with a difficult but tangible solution, frequenting poetry readings and becoming the hanger-on of the poet crowd. Another poet friend, Susan Briante, tried to appease my increasing sense of frustration: “You can actually say that there are some right ways and wrong ways of writing a story, but not so with a poem,” she reassured me. Her explanation felt like an absolution: I no longer needed to try and understand poetry; it was the mystery of consciousness manifest, and one could only grasp it through faith. Still, for one misguided moment, I felt less of an artist. I could read a story in a graduate workshop and immediately judge where it was in the developmental process, with a thorough and detailed identification of the how and the why. I could not do this with poetry. Did this make fiction less creative? Why did fiction require so many rules? Were we really sub-artists? Immured in the structures of narrative, like Charles Baxter once decried, unable to break free to leap and swim in the tides of chance?

It was as if I had forgotten how much I myself had struggled with the mastery of prose, how in my first undergraduate workshop long ago I had bitterly complained to a fellow writer: “The only stories Dufresne likes are the ones that don’t follow his own rules.” I had forgotten that knowledge about fiction hadn’t been handed to me with a how to manual; rather I’d had to scrape it off from the surface of story after story, samples sectioned from myriad lines, words, image, each carefully examined and annotated, and compiled into endless theories that sometimes contradicted one another. I had forgotten how it was that cumulative effort had turned my understanding of fiction into body memory, so instinctual that it couldn’t be separated from the physical act of putting words down on paper anymore than a human could be separated from the air she breathes. Still that inferiority complex nagged on. “Your best prose reads like poetry,” some of my most loyal admirers have said of my writing. It had never occurred to me to question that compliment, even with its implicit connotation of the inferiority of my form.

Susan Briante / photo from: http://delirioushem.blogspot.com/2008/12/susan-briante-solstice-so-jet-stream.html

Yet it was impossible not to feel vindicated when neither the brilliant Briante nor any of the other poets whose talents I had secretly envied during Kumin’s and Campbell’s class felt comfortable structuring stories under the heavy heft of realistic characters and ordinary situations during their service in the mandatory fiction workshop. I admit I regressed to childish competition. I wanted to stand up, spittle on my lips, and shout: “You want the fiction? You can’t handle the fiction!” I constructed a working metaphor for myself to better intuit the difference between the forms: fiction was a symphony composed of multiple instruments, each with a melody that complements the others, its artistry relying on harmony and structure, whereas poetry for me was chaotic jazz-fusion, showcasing amazing technical skill and inventiveness, relying more on the individual improvisation and less on the cumulative effect of careful orchestration.

Even this elaborate analogy falls short of the truth, of course. What about the orchestration of forms like the sestina, with such an exacting pattern that I am convinced only a mad mathematician could have invented it? And what about the psychosis-indulging image juxtapositions of William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, or the structure-morphing Moby Dick, or the story in Robert Haas’ poem “A Story About The Body”? Are these symphonies or fusion? As I’m writing this, I revisit my friends’ words: it’s like trying to define what makes art. I cannot say what makes a poem different from a piece of fiction. But I can tell you that fiction, with all its exacting elements, demands that I create curvy well-signaled highways out of angular, mysterious mazes, or, perhaps more accurately, that I build sturdy structures out of the sandy texture of words.

Ironically, it’s this love for the density and intensity of words that began to fuel my interest in poetry. From the time I was introduced to the works of Lynda Hull, Sharon Olds, Gary Soto, Billy Collins, Stephen Dunn, and Pablo Neruda, to name just a few favorites, I began to appreciate the beauty of juxtaposition of abstracts and tangibles, or the humor that could be gleaned out of a single, well-rendered image, or from the heartbreaking insight enveloped in the cellophane of one well chosen word. Still today, I play a word game I invented for my husband. We gift each other with the utterance of a single word, savoring the physical sensations that speaking that word can arouse. “Today, I give you crepuscular,” I tell him. He responds with a “wispy” and I thank him, saying it out loud a few times because wispy feels so good in my ears and on my tongue.

It would seem that this attention to language would be integral to any writer’s work, regardless of genre. Yet, there are schisms between poets and fiction writers. That semester of poetry in Florida had certainly made me feel like a convert, somewhat clandestine and apologetic, and this feeling of being an outsider to the art of poetry got worse when I attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where years later I went for a second MFA. There, poets and writers of fiction could not take each others’ classes and were scheduled on different days of the week, so that a poet sighting became a rare thing if you were a fiction writer. This sectarianism seldom went unchallenged, in spite of a faint sense of wrongness on which we’d casually comment from time to time; we simply accepted, as our professors did before us, that the two forms belonged to what amounted to entirely separate programs.

I was curious, though, allured by the promise of something different and mysterious, an almost sexual quality to my intransigent forays into poetry. During my MFA at Iowa, I instituted what I called breakfast with a poet. In the mornings when I didn’t have workshop, I would go to the local bookstore and grab two or three titles by the same poet. I’d buy myself a latte, and read the books while nibbling at a muffin. After I was finished, I felt that I had become intimate with the details of the poet’s life. In this way I made up for the relationships I could not have in person with the poets in my program.

Cristina Garcia / photo by Norma Quintana

It turns out this illicit attraction to the other genre is not original with me. At a reading in Miami, while on tour for her book Monkey Hunting, novelist Cristina Garcia attributed the success of her lush prose to the fact that she starts every writing session by first reading a book of poetry. A teacher of mine at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Chris Offutt, said he never sat down to write fiction without first reading at least one poem. And during my teaching demonstration while applying for my current job at Georgia Southern, where I now teach both budding poets and fiction writers, I asked the class if anyone had ever tried reading poetry to get inspiration for fiction. “I read at least a few poems before I start writing,” I explained: “It helps me to orient myself emotionally for a story. Has anyone ever tried that?” The first hand to shoot up was that of Peter Christopher, a Pushcart nominated, NEA recipient, and a much beloved and admired fiction writer.

Maybe Andrew Hudgins was right: so many of us fiction writers are, after all, closet poets; or perhaps some of us seek the fluidity of poetry as the necessary contrast to the solidity of prose: a man may live on a mountain and know how to climb steep heights, yet despite being unable to change a sail or throw a net, from time to time this cold-weather man may like to leave the stolid beauty of the mountains for the pleasure of a creaking sailboat, for the gentle slap of the waves on the hull and the salt of the sea on his white, sunless skin. Not only for the time on the water, but also so that on his return he might better appreciate the hard-edged clarity of a snowy mountain peak.

That day at Sewanee, after I’d left the talk and began wending my way back across campus to my room, still mulling over Hudgins’ joke, I saw two fiction fellows heading towards the lecture hall. They waved and beckoned me over to their shady side of the street. “We’re going to see Hudgins,” they announced with welcoming smiles. “I just came from there,” I told them, gently declining their unspoken invitation by keeping on my side of the road. The two fiction writers looked worriedly at me and slowed to a halt. “Well, is it any good?” they asked me, their bodies already poised to flee. I paused, reconsidering my emotional reaction to Hudgins’ joke. What is poetry, after all? A mystery I can access but cannot entirely understand. Yet one that feeds my interest and search for perfection as a writer, nevertheless. With this realization, I could then be grateful for the elusive mystery that will forever illuminate my love of writing, whether it comes from a form whose theories I’ve learned or one that remains a dream of magic. Mystery is what keeps us interested in discovery; mystery is the basic element of self-awareness.

I smiled at my fiction friends then. “Oh yeah,” I replied, encouraging them to go, perhaps recognizing something in them as fellow truth-seekers. “But, you know,” I confessed; “it’s all poetry to me.”

About the Author

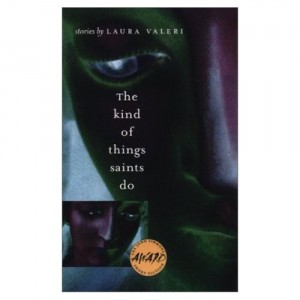

Laura Valeri is the author of the collection The Kinds of Things Saints Do, winner of the Iowa/John Simmons Award in 2002 and the Binghamton University John Gardner Award in 2003. She was a Sewanee Walter E Dakins Fellow in Fiction in 2008 and earned her two MFA’s from Florida International University and from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her work appears in Glimmer Train, Gulf Stream, Big Bridge, Waccamaw, Inkwell/Literary Potpourri and a collection of essays by Italian Americans published by Creative Nonfiction and Otherpress, titled Our Roots Are Deep With Passion. She is at work on a novel, a screenplay, and a collection of linked short stories.