Creeds

We were noble, forgiving, self-sacrificing. We were messengers riding out front and sometimes, historically, were killed for the news we brought. We were martyrs, marchers, confessants, confessors, a conservative avant-garde. And every year, we staged a crucifixion.

Marked

A weird mix of privilege and oppression colored my grammar school years, the blessing and burden of being singled out as special. At first it was the anointing looks my elders gave, later I felt it inside. They all said I’d grow up to preach. Even my parents’ version of my birth-story took this tack: the doctor’s swat, my deafening howl, and from behind the white mask the diagnosis: “We’ve got a preacher!” (Likely a standard delivery-room quip, yet in my case how helpful an augury it seemed.) Later on, a pious youngster, I had no reason to chafe as grownups all around me invoked this destiny constantly. Their presumption, to my eyes, was discernment in the Apostolic sense (“To one is given through the Spirit the utterance of wisdom…to another the discernment of spirits”). Yes, some Lord-crafted lodestone lay at the seat of my soul — a tugging fate. I was, as Saul Bellow’s Charlie Citrine describes himself in Humboldt’s Gift, “stamped and posted and they were waiting for me to be delivered at an important address.” Evangelical Wunderkind: how could I object? To be a preacher — especially to be meant to be one — was to know your business on earth, to be the guy who got it straight. Sanctification, veneration, a smidgen of fame? Yes, please — all leavened, of course, with Edenic humility: we were, one and all, punted from Paradise long ago and let none forget it.

So I owned my youthful calling, embodying it gladly as I then knew how. By heart, as early as second grade, I had memorized great chunks of the New International Version, chapter and verse. We Cunninghams attended service thrice weekly, and glued to a pew for each of these hour-plus sermons I’d often pluck the small yellow tithing cards from the pew box and, in fields reserved for designating the month’s monetary pledge or submitting prayer requests, would scratch down abbreviated exegeses of the pastor’s message, dropping these into the deep velvet bag that came around during the offertory:

Our faith should be fragrant to people around us, like the oil the woman uses to wash Jesus’ feet.

Zaccheus climbing the tree to see Jesus reminds us that we should rise above our sinful world in our love of the Lord.

Fundamentalist evangelicalism is not without its pseudo-literary pretensions, and a regard for these. That I stagnated in the banal substratum of the children’s Sunday School (a pedagogy of felt boards and popsicle-stick crucifixes), that I moved up early to the ostensibly more sophisticated climes of Youth Group, was widely known. To my peers in Sunday School through all my churchgoing years, I was the go-to man for Biblical reference, commentary, and interpretation.

Weekdays at my public school I behaved as this church reputation demanded, frequently broadcasting my faith in overwrought testimony to friends, or insufferable commentary on their un-Christ-like behavior, less frequently in extra credit reports on the life of Jesus, evidence of the End Times in current events (material cribbed from The 700 Club), or the latest archeological efforts to pinpoint the final dry-dock of Noah’s Ark. I scrutinized all my teachers (was Mrs. Natenkemper a Christian?). At every opportunity I dragged a friend to church. Most significantly, every time my sinful nature got the better of me (that is, daily), I condemned myself. Each instance of lying or lust, each “curse word” or mere taint of doubt in the font of faith would bring out my own private cat-o’-nine-tails. Suitably bloodied, in thrall to the horrors of hellfire, and believing that when the rapture came I was to be deservedly left behind (as the latterly bestselling evangelical thrillers have put it), I prostrated myself before God, awaiting his forgiveness — and fearing his wrath.

Weekdays at my public school I behaved as this church reputation demanded, frequently broadcasting my faith in overwrought testimony to friends, or insufferable commentary on their un-Christ-like behavior, less frequently in extra credit reports on the life of Jesus, evidence of the End Times in current events (material cribbed from The 700 Club), or the latest archeological efforts to pinpoint the final dry-dock of Noah’s Ark. I scrutinized all my teachers (was Mrs. Natenkemper a Christian?). At every opportunity I dragged a friend to church. Most significantly, every time my sinful nature got the better of me (that is, daily), I condemned myself. Each instance of lying or lust, each “curse word” or mere taint of doubt in the font of faith would bring out my own private cat-o’-nine-tails. Suitably bloodied, in thrall to the horrors of hellfire, and believing that when the rapture came I was to be deservedly left behind (as the latterly bestselling evangelical thrillers have put it), I prostrated myself before God, awaiting his forgiveness — and fearing his wrath.

Pageantry

Even more than the frankincense and manger-straw of Christmas, I loved our Easter musical. At the production’s heart was a long, shockingly explicit crucifixion scene. This scene always featured our Youth Pastor, a thirty-something amateur bodybuilder whose biceps could hardly have been circumscribed by my belt at the time, and whom I loved as I could love no other hero.

Call him Sid. Garbed in the short white skirt of a Roman soldier, capped by a gold-painted plastic helmet complete with ear-guards and red-bristled centurion mohawk, Sid, heading up a corps of soldiers, lumbered down the aisle of our spot-lit gymnasium-turned-theater lashing a short whip across the back of a staggering, cross-bearing Jesus (an absurdly Anglo churchgoer named Keith). “Move it!” Lash! Lash!

Off in the side-rows I sat, a frightened juvenile baring my orthodontia at the melodrama. I had a passion for that Passion Play — whose horrors, I’m sure, scarred the psyche of many a kid younger than I.

I recall something not vaguely sexual stirring in my boyish limbs during this scene. And for weeks following Easter I would replay the high pornographic drama of Keith’s/Christ’s blood-covered stagger toward Golgotha, recreating the scene with colored felt-tips in the privacy of my bedroom: Christ hunkered under the splintery cross with red globules oozing down face and spine, as though the day rained blood. Some years the play’s carnage was thicker than others — depending, I guess, on the varying pathos of the backstage makeup people. What I see now is a veritable Jackson Pollock of gore from Keith’s shoulder blades to the waistline of his diaper-like loincloth. And there in the blinding spotlight behind him is Sid. “Move it!” Lash!

Heroics

Sid’s magnetism generated from those massive biceps and pecs, fortified regularly with half-cups of powdered amino acids and cheek-reddening bench-presses. He was, as my older brother liked to say, “ripped.” Early every Tuesday before school, I and a few church peers would meet Sid at a local Denny’s for Bible study. Afterward he would drop me at my junior high. What an enviable sight I felt on those mornings, climbing down out of Sid’s sparkling Bronco. “Dude,” I imagined schoolmates murmuring (particularly the tougher boys who shoved me around now and then), “is that his dad? That guy’s ripped!” Unlike the pop stars and pro athletes serving as objects of hero-worship for those kids, Sid was immediate and real.

He was also a walking aggregation of adolescent preoccupations, a fact which had repeatedly landed him in hot water with parents at church. Numerous mothers (mine no exception) scowled at their kids’ reports of Sid’s pranks, which included leading his Christian charges on midnight campaigns toilet-papering pastor Kellogg’s house, staging public spectacles like the “dollar dive” at the local mall (wherein a dollar, planted in plain sight, was rescued with a sliding body-dive across the polished floor a second before a hapless shopper could bend to pick it up), or tormenting the boys of Youth Group with top-floor “snuggies” (better known as “wedgies”).

I found these hijinks inspired, and though I walked then in mortal dread of the snuggie, I still give Sid points for originality. He had, I remember, a fetish for horror movies, and even screened Night of the Living Dead for us during a church all-nighter, only to leap up — in a different kind of horror — during the nude grave-dancing and orgy scene, chuckling as he scrambled to stop the tape, “Whoa, okaaay, time for a different movie.” How refreshingly distinct he was, blunders and all, from the bland — and on occasion excoriating — moralism operative in our congregation. Sid liked fart jokes. He drove fast. He enjoyed a plug of Kodiak or Copenhagen.

Prankster or not, however, Sid was no maverick when it came to theological mores — creed-wise he was as conservative as my mother, and could dish out moral spankings and Biblical shamings like the best of his elders. Still, he was the first nonconformist adult I ever knew. Lively renegade and irrefutable man’s man, he made my kind of Christianity — its prayer groups and Bible flashcards — inarguably cool. I was drawn to him, intoxicated by him. I wanted to be Sid.

Storytelling

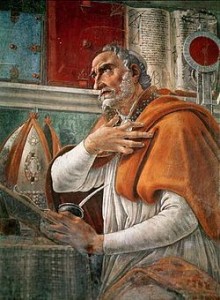

Saint Augustine, in his Confessions, tells the fascinating story of his conversion. Lingering in the courtyard of his mother’s house one day, he heard a disembodied child’s voice imploring him to take up the scriptures and read. Obeying, his eyes fell upon some lines from Saint Paul and immediately, “it was as though the light of confidence flooded into my heart.” He dashed inside to tell his mother he’d been saved.

Saint Augustine, in his Confessions, tells the fascinating story of his conversion. Lingering in the courtyard of his mother’s house one day, he heard a disembodied child’s voice imploring him to take up the scriptures and read. Obeying, his eyes fell upon some lines from Saint Paul and immediately, “it was as though the light of confidence flooded into my heart.” He dashed inside to tell his mother he’d been saved.

Reading this account today, I realize that all conversion experiences have an essential commonality: one is seized by the sense of one’s own crucial position inside a story — one’s life clicks into place as a facet in a much larger tale, where the world’s salvation hangs in consequence. A moment of profound transformation arrives and one is, for a glorious or gloriously humiliating instant, placed unmistakably center-stage. Implicitly, Augustine’s hot-flash of “confidence” at the moment of conversion is an awakening to, a confidence in, narrative — the authentic, life-changing power of story.

The evangelical emphasis upon personal Testimony — and I can’t say how many testimonies, stirring and convulsive, I heard in church — exemplifies the enduring importance of stories and storytelling to a spiritual life, and to the life of the church in which I grew up. “And from that moment forward I renounced my old ways,” et cetera. “I became part of The Story.”

To belong, it turns out, always means to belong within a narrative.

Iconography

Having executed my detailed crucifixion drawings, I would carefully destroy them. What would my mother have thought to find them? Or would the weird intermingling of evangelical zeal and proto-sexual perversion have occurred to her? It was a kind of highly protestant self-pollution, enacted in the locked sacrarium of my bedroom, followed by a quick disposal of evidence — but maybe Mom would not have punished me as she would were she to find me in the grips of a pornography purely secular.

In retrospect I think I was suffering some psychological mix-up, a sort of erotic transference relating to my idolatry of Sid and his casting as Christ-torturer. Involuntarily I became a Christ-torturer myself. That I felt no keen guilt — only momentary pangs — seems strange to me now. At the time, I guess, it was all in the spirit of the Pageant. (And was I so different from, say, those icon painters of seventeenth century northern Europe, whose dying Christs resemble horrid dinner delicacies cooked rare?)

The elaborateness of our Easter Pageant might surprise anyone unfamiliar with the fundamentalist Christian style, but I’ve only grazed the iceberg. Earlier in the play Jesus rode up the aisle astride a live donkey, hailed by an uproarious Jerusalem of smiling children by the hundredfold, each waving a palm branch. Utterly innocent of liturgical foundations or efficacious ritual, the evangelical spirit is nonetheless obsessed with the theatrically ornate. It wants spiritual pyrotechnics, gratuitous public confession, ticklishly unnerving reports of things apocalyptic or Satanic. It wants tearful testimonies of the once-demon-possessed; the soft-spoken come-clean of a former pedophile; the open repentance of a saved homosexual (one unforgettable Sunday night in seventh-grade, I witnessed this last).

Were we hateful? No, not outright. Prurient? Sure, if inadvertently. Clueless? Yes, in our way. Bigoted too — though never militant, never even particularly aggressive. Beyond casting the always conservative vote, campaigning on the matter of prayer in school, and being staunchly “pro-life,” we were basically apolitical (the amped-up lust for public office of the Christian Right over the last eleven or twelve years still surprises me). Naturally, we didn’t see ourselves as fundamentalist; most of us were happily “non-denominational,” floating from Baptist to Methodist to Nazarene. We went wherever the Spirit was felt.

Absence

To write of these things now is tricky, a bit like trying to extract from an old photograph the substance of a much younger self, to snap figure from background in order to prop it up in three dimensions — “There, gotcha!” But for all the self-violence, sanctimony, and other vinegary psychology of those formative years, they amount, almost despite themselves, to something more meaningful than mindfuck. I now disown the institution of the church entirely, and yet when I’m honest I recognize that never in later life have I felt so warm, deep, and validating a sense of inclusion within a community, a total involvement, an enveloping familial belongingness.

My ultimate defection from “The Story,” and thus from its belongingness, became a crucial contour in the narrative of my life — the absent communal warmth defines me as much as did its presence. I grew up to be a writer. If I now live outside “The Story,” it’s for the sake of stories in general, my own life being but one among many. “Never again,” says John Berger in his novel G., “will a single story be told as though it were the only one.”

I can never go back to that particular narrative, alluringly warm in memory but frightfully narrow in truth, because I belong, in a sense, to all stories — or anyway, some involuntary force has dedicated me to the ideal of such belonging. John Keats meant something similar, didn’t he, in calling the poet “the most unpoetical of anything in existence; because he has no identity — he is continually in for — and filling some other Body.”

Iconoclasm

Sid self-destructed. His disapproving elders may have seen this coming from miles away, but it was the horror of my youth. One Saturday we learned he’d been arrested at home by — preposterous! — FBI agents on charges of Grand Theft. He was suspected of stealing binders full of vintage baseball cards from a shop run by a kid in Youth Group. Oh pathos! Oh betrayal! Sid admitted guilt right away. He was arraigned and carted to prison within days.

Sid self-destructed. His disapproving elders may have seen this coming from miles away, but it was the horror of my youth. One Saturday we learned he’d been arrested at home by — preposterous! — FBI agents on charges of Grand Theft. He was suspected of stealing binders full of vintage baseball cards from a shop run by a kid in Youth Group. Oh pathos! Oh betrayal! Sid admitted guilt right away. He was arraigned and carted to prison within days.

Pastor Kellogg brought in counselors for us distraught kids in Youth Group. I remember the counselors’ chart delineating the stages of grief. It seems to me, even now, an apt approach to our trauma. This was the first grievous loss of my life.

Before the close of my seventh grade year some months later, we heard that Sid, released on bail, had promptly robbed a women’s clothing store in broad daylight, telling the clerk there was a man outside with a gun. Back to jail it was.

I understood then that I’d never see him again.

Reverse Augustine

Early on I hurried, seeing the light, hurdling to rise. There was so much to learn, to internalize, to testify, so much sinfulness to shed, only for this dogmatism to be abandoned and mostly forgotten. There’s no pocketing enlightenment. It gets lost in the wash or goes the way of pennies and pens down the back of the couch. The guys at the Quickie Lube find it dried to a crust under the driver’s seat. Or maybe that’s putting it too cynically. I’m more of a mind with T.S. Eliot: “There is only the fight to recover what has been lost / And found and lost again and again.”

In the shock-wave of Sid’s sudden absence, I experienced the harsh clarity of an examined life. Well-meaning adults, some of them Sid’s erstwhile detractors, filled his place in Youth Group. How could they be anything but pale, lifeless, hypocritical? It was as if I suddenly stood outside looking in, seeing what I and those around me had always glaringly been, what I’d never realized we were, what I could never fully be again. This state of helpless criticism brought me zero intellectual pleasure (not for nothing does the word criticism derive from crisis). I was tearing away, experiencing the agony of having my narrative, the only one I’d ever known, cauterized.

Compared to the belongingness of my upbringing, my “churchless” life — two decades now — looks like pure post-modern alienation. In many respects it has been an outsider’s existence, marked frequently by the disturbed sense of an atomized modern life, of adults adrift in a proximity everywhere only vaguely defined (neighbor, co-worker, merchant/customer), of mere politeness and civility — and yes, occasional anomie — underlying a pandemic of spiritual isolation.

We like to believe in the “autonomous self existing independently, entirely outside any tradition and community,” suggest the authors of the seminal cultural study Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (1985). But they go on to note that the self as tabula rasa is a “powerful cultural fiction.” The soul, always formed by community, needs community in whatever form, needs in some way to belong.

But I also agree with James Baldwin where he writes, “Art is here to prove, and to help one bear, the fact that all safety is an illusion. In this sense, all artists are divorced from and even necessarily opposed to any system whatever.” The writer, whom the work of imagination renders at once honoree and outcast, is everywhere and nowhere at home — and that in itself is belongingness of kinds.

From the Biblical gospel of my youth I would graduate, eventually, to the gospel of American transcendentalism as penned by Thoreau and Emerson, then on into wider literary/aesthetic realms. My devotion today is the muddled life of the creative mind, complete with chronic ambivalence, allergies to dogma, and those inchwise flights of elation won at the price of weeks — more often months, still more often years — of thematic, syntactical, and lexical agony. I’ve always held that embracing my literary yen was the more wholly authentic means of living up to my cosmically postage-paid sense of self, that prior I’d been mistaken if not misled in my felt destiny of preacher-to-be, and that all the time I was headed for an unavoidable appointment with my own self-development, my inevitable awakening id. To a degree, all that is true. Yet while I do find the life of writer most suitable for me — even “fated” — how much do I owe to that profound, incalculably formative touch of consecration bestowed by the church, back in the years when I first came to know what a “calling” felt like?

And what do I owe Sid? To what deep degree did his rebel tendencies provide me a taste of an entirely different, free-thinking life? Maybe Thoreau and Emerson clicked perfectly into the niche Sid first carved.

My early belonging, though I renounced it, formed me in some incontrovertible way — formed me even by virtue of renunciation. For all the delusions and agonies, I cannot unweave that piece of my history from the whole. “The Story” shaped how I see the world.

I’m grateful.

Links & Resources

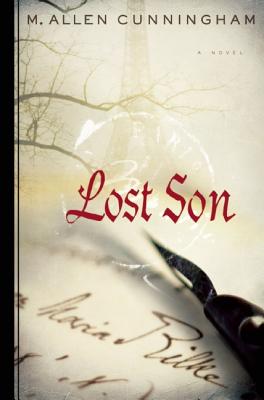

- For more on M. Allen Cunningham’s work, please visit the author’s website.

- Follow M. Allen Cunningham on his blog.

- Here is a 2005 interview with Cunningham on the release of his debut novel, The Green Age of Asher Witherow, a gothic coming-of-age tale set during the boom and bust years of an immigrant coal-mining town in nineteenth-century California.