Probably the right place to begin this story would be with Evans sharpening his beautiful, bone-handled carving knife, the flashing of the steel, the fine blade capturing the glitter and shiver of the candle flames, of candle light reflected on polished silverware and the wine glasses of the grownups.

Probably.

But I’m no George Garrett—and that’s the first paragraph of his last story, “Thanksgiving,” published in the spring 2008 issue of Blackbird just four weeks before his death—so I’m going to start somewhere else.

Specifically, on a brick walk leading away from the famous lawn that’s central to the University of Virginia. It’s 2004. I’m nervous and excited, because I find myself in the impossible situation of having published my first book, a novel about a strange Alaskan eddy of World War II, and I’m here for the Virginia Festival of the Book.

Here but not here, lost in thought, and so I don’t realize until it’s almost too late that I’m about to cross paths with none other than George Garrett himself. Back then, there were few writers whom I’d more wanted to meet, and here he was, headed straight for me, the man I thought of as “The Source”: Garrett had been the prized mentor to the faculty of my graduate writing program, and one of the founders of AWP, and so, despite not having worked with him myself, I felt in his debt. The thing to do, obviously, was to thank him.

Here but not here, lost in thought, and so I don’t realize until it’s almost too late that I’m about to cross paths with none other than George Garrett himself. Back then, there were few writers whom I’d more wanted to meet, and here he was, headed straight for me, the man I thought of as “The Source”: Garrett had been the prized mentor to the faculty of my graduate writing program, and one of the founders of AWP, and so, despite not having worked with him myself, I felt in his debt. The thing to do, obviously, was to thank him.

It was sunny and warm and Garrett was just a few months away from publishing his tenth and final novel, Double Vision, which would join eight volumes of short stories, seven books of poetry, and more than three dozen other plays, nonfiction works and edited collections. Indeed, Richard Bausch once wrote that there was “no writer on the American scene with a more versatile, more eclectic, or more restless talent than George Garrett.” Kelly Cherry said Garrett was “the best friend every writer who ever knew him had.” All I had to do: say hello. Hello, and thanks.

He smiled. I smiled. We passed. He continued toward the lawn. I toward the parking garage. With each step, the silence grew. I’d like to say that my inability to bridge the gap between us had something to do with my still being rattled by an audience member who’d just asked me, “But what of your book is true?”

Or the fact that, earlier that morning, I’d received an unsettling email—from the protagonist of my novel. (Don’t ask me—yet—how that’s true.)

The truth is, my courage arrived late, and when I finally turned, he was gone. And so my education in narrative distance began.

*

Apart from Bausch and Cherry, I’ve heard Garrett described many times in that most wonderful of awful phrases, or vice versa: a writer’s writer. But I like the term in this case because the tale Garrett tells in his short story “Thanksgiving” is of a writer’s writer—that is, the writer of a writer, a protagonist who is the author of his fellow characters, and consciously so. “See?” Garrett seems to say when we encounter one nested story after another (and another), “here’s what’s really happening.”

I’m happy to be drawn in as close as I can get, because that’s the kind of reading I love to do. Of course, close reading—and this I know, because I work in an English department—is never a guileless exercise. But I’ll be candid about my agenda here. I want to use Garrett’s story to illuminate a tricky aspect of literary craft: narrative distance.

I’m happy to be drawn in as close as I can get, because that’s the kind of reading I love to do. Of course, close reading—and this I know, because I work in an English department—is never a guileless exercise. But I’ll be candid about my agenda here. I want to use Garrett’s story to illuminate a tricky aspect of literary craft: narrative distance.

I also want to use this essay to do something trickier, something more personal, which is to return to that path at UVA, summon up Garrett’s ghost from the bricks, and talk.

*

Let’s walk back to that opening paragraph: “Probably the right place to begin this story would be with Evans sharpening his beautiful, bone-handled carving knife…” Starting with that first word, probably, Garrett sets the tone with a signature move—an act of intimacy that, upon reflection, makes us feel dizzyingly distant from the story. “Probably,” Garrett writes, uncertain, deferential. He’s ready to grant that the story might start better elsewhere, and we readers take this kindness, smugly pocket it and continue, only to realize a few words—a few sentences—later, Well, wait—if this isn’t the right place to begin the story, what is? So we read further, hoping to discover the answer.

And Garrett’s got us: we’re in.

In where? A comfortable home outside Philadelphia, it turns out, at an elaborately laid Thanksgiving table. We’re here because the narrator wants us to hear a story often told at this table by his father-in-law, about a trip to South America in the 1930s to find the source of the Orinoco River. The narrator wants to tell this story, but also comment on it, and, occasionally—get our input? Or so it seems. Because once the narrator has set the stage and hung his frame, he concludes this way: “More than a touch of Norman Rockwell in this opening scene.” Full stop, a declaration. Followed quickly by a question: “Wouldn’t you say?”

We’re only a page or so into the story, so we could dismiss this as nothing more than a feckless, anxious narrator being coy, but then we steal upon the next line, across the section break, which isn’t the narrator’s at all, but rather a headline from the March 29, 1931 New York Times: DICKEY PARTY READY FOR ORINOCO QUEST.

And yes, it’s a real Times article. Indeed, as I trotted off in search of it, the only thing that eased my concern that I was “cheating”—sniffing around for the story behind the story, rather than just reading the story itself—was the growing realization I was doing exactly what Garrett hoped. He didn’t want just readers, but collaborators, people who might become as obsessed with the story as he.That’s me. And my goal wasn’t (and isn’t) to suss out the “real” story, but rather to see how narrative distance itself is the real story. Throughout “Thanksgiving”, the narrator works hard to span two forms of distance. One, between what’s fictional and what’s made real; and two, the distance of time: this is a story of something that happened long ago.

He addresses both types of distance in this odd paragraph, which comes just after that Times headline:

Please note that all of these people, [the narrator says] including Evans and [his wife] and some of the others at the dining room table, are dead and gone now. They live on, if at all, only in the memory of others like myself…. Even though it may sometimes be strictly and factually correct, memory is the source of much fiction. Although much of what follows (and, indeed, much of what has already been said) is as accurate and authentic as I can make it, it is all gleaned from memory, of my own and of others.

Watch how the narrator paradoxically increases intimacy by expanding distance: This happened decades ago; those involved are dead—not just dead, in fact, they’re “dead and gone” (emphasis mine). And: “memory is the source of much fiction.” He says all this, and yet, we’re not put off because these admissions of frailty engender trust.

Kelly Cherry made much the same point in a wonderfully searching appreciation of Garrett that ran in the same issue of Blackbird as “Thanksgiving”: “Memory and imagination are always at play in Garrett’s work,” she wrote. “For him, perhaps, the work is not complete until it contains both memory and imagination. It is the two together that both fuel and unify his work.”

That’s exactly what’s happening here. We’ll soon encounter a flood of facts—down to latitude and longitude—that make this feel very much like every colonial exploration story we’ve ever known: They travel south, to Venezuela. It is hot. They start up river. They find friendly Indians. They travel further. There are flies, mosquitoes, malaria, suffocating heat, dwindling supplies.

The suburban setting in which the story is told, on the other hand, sounds lovely: “As I recall it now, we would sit by this fireplace, firelight dancing, dogs curled up and snoring deeply at our feet, passing a bottle back and forth and telling stories real and imaginary, true and false. To be sure, there were always changes, revisions, additions and omissions, different degrees of emphasis.”

The suburban setting in which the story is told, on the other hand, sounds lovely: “As I recall it now, we would sit by this fireplace, firelight dancing, dogs curled up and snoring deeply at our feet, passing a bottle back and forth and telling stories real and imaginary, true and false. To be sure, there were always changes, revisions, additions and omissions, different degrees of emphasis.”

To be sure. Although, of course, we can’t be. The narrator, after all, mentions they passed the bottle “back and forth.” And, since we’re reading this closely, perhaps the bottle gets passed to us as well, which makes us both a part of the telling and responsible for its inaccuracies.

Collaborative storytelling is a messy business, of course, as actors, screenwriters (Garrett did that, too) and authors who receive emails from people claiming to be characters in their novels know.

But Garrett makes things even messier by breaking a basic rule of adventure stories, which is to leave the outcome in doubt. When he writes, with leatherbound, thumping flourish, “from the outset of the return trip, they were starving. If the malaria didn’t kill them one and all, starvation surely would do the job,” we don’t get too concerned, because we know the storyteller-participant, the narrator’s father-in-law Evans, survived.

So what, precisely, is this narrator up to? How can he say, “starvation surely would do the job,” when he knows—and he knows we know—starvation didn’t?

Somewhere inside us an English major pops up: oh, right, this story began around a Thanksgiving table, groaning under the weight of the food it bore, and here they are in the jungle starving: this is a story about lack and plenty.

Or maybe we think: no, this is a story about truth and lying, and so the use of that “surely” is simply to point out that nothing is ever so sure….

Surely, but the more striking realization we should come to at this point is that we’ve traveled a great distance from the putative subject of this story: old man Evans in front of the fire. But it’s been ages since he last spoke; the narrator has chosen to summarize Evans rather than quote him. And time’s running out: the jungle expedition is almost over.

“And here,” the narrator interrupts, “is the place where Evans would begin to tell us his favorite story about the expedition.” Just like that, we’re drawn back in—literally, with the help of that “us”, and of course, rhetorically, since we go straight into an Evans monologue. Look how the story’s tension derives entirely from the form of its telling. The heat, the jungle, the Indians—all feint. We are reading not to find out how it ends, but whom it ends. Turns out we’ve stumbled into a Garrett master class on character, and there’s a seat open just to his right.

To his left there is old Evans, he of the knives, and sure enough, Evans has finally started to tell us how, on the brink of starvation, he and a companion leave the struggling party to discover the source of some far-off smoke. They find a village—mysteriously empty but for a giant kettle of soup. They bear it back to the exploration party; everyone is restored. As thanks or payment, they return the empty soup vessel with all their remaining trading trinkets, including a case of machetes. Then it’s back into the boat, down the river, civilization.

And now, the narrator quietly steps back into the text.

Evans usually elected to end the story there, coming to closure with the unanswered and probably unanswerable question: What on earth did these people, whoever they might be, in a lost and gone little jungle camp or village, believe had happened to them? Best guess was that they were Stone Age people. Suddenly strangers, alien to them in every imaginable way, arrived, took their food and left behind, like a gift of the gods, a dozen steel machetes. How that strange gift must have changed their lives (for the better?) ever after. It gave Evans a sense of satisfaction.

And, even if we don’t like to admit it, it probably gives us satisfaction, too. They did make it safely back, after all. They didn’t die, and we knew they weren’t going to die—surely we knew—but we were probably nervous anyway. Because that’s the anxiety of fiction, even historical fiction—not only of reading it, but writing it. The outcome is not in doubt, but for the fact that, since it’s a novelist at work and not a historian, it is in doubt.

When I wrote my historical novel, I mistakenly thought my most important job was to get the facts right. Facts are important. But, as I learned when my protagonist sent that e-mail, there’s more to the truth than the truth.

Garrett makes this point himself at the close of his story. He twists the telescope again so that we are, once again, quite far from the story. Where once we were intimate with the narrator—we were seated close enough to the turkey to taste it—now we realize that the person we’ve spent the most time closest to, the narrator, is the person we know the least.

Thus the narrator springs his trap. He’s gotten Evans to tell his tale, waited patiently through all the colonial flourish and bravado, and now he responds. He tells Evans he read an article not long ago that examined the history of these same “lost tribes”: apparently, they knew a precarious peace, until one day, a case of machetes mysteriously fell into the hands of one tribe, who went on to butcher and enslave all the others. This tribe came to be known as the “Long Knives.”

Thus the narrator springs his trap. He’s gotten Evans to tell his tale, waited patiently through all the colonial flourish and bravado, and now he responds. He tells Evans he read an article not long ago that examined the history of these same “lost tribes”: apparently, they knew a precarious peace, until one day, a case of machetes mysteriously fell into the hands of one tribe, who went on to butcher and enslave all the others. This tribe came to be known as the “Long Knives.”

And we think of those machetes Evans left behind.

And we think of those knives at the beginning, flashing around the table.

And we think—what is this narrator doing to Evans? To us?

And we realize: George Garrett has just shown us how to go out on top. A month from his death, he publishes one of the best stories of his 50-odd years in letters, securing his position not only as one of the 20th century’s great American authors, but also a man who’d written one of the best stories of 21st to date. (If only he’d lived until the New Yorker did an “80 under 80” list).

*

“Maybe I should write my own ending,” the narrator says at the conclusion of Garrett’s story. “I owe him that much.”

Maybe you should tell me what happened, my novel’s narrator e-mailed me that morning in 2004. I’m owed that.

“Invisible,” Garrett writes at the end, “I join them, the five survivors, five ghosts now, standing at the handrail of that ghosted and ghostly Mississippi paddle wheel steamer” as they leave the Orinoco behind: “The men and Mrs. Dickey stand at the rail watching the continent disintegrate into the delta. They are patiently watching and, by now, beyond speaking.” They are drinking, he says, and

they pass the bottle, and its dwindling contents, back and forth until there is not more than a big swallow left and the bottle is in the hands of Evans Dunn. Who shakes it and tips it up and drinks it empty, then tosses it high, wide and handsome, all aglitter in the late afternoon sunlight, to splash in the water and vanish for as long as forever may be.

The tug of the camera pulling back is visceral. And so, too, the language pulling us in—they are “beyond speaking”; Evans retrieves his full name, “Evans Dunn”; the alcoholism we’re told would later kill him is, via that bottle, sent sailing “high, wide and handsome.” If it takes me 80 years and as many books just to come up with three adjectives as unexpected and as perfect, then it will have been a life well lived.

Because what Garrett has done here is both simple and astonishing. He not only dares to have his characters ride off into the sunset, but he sends the story sailing, too. With this final, very real, very physical (and, of course, very fictional) break—that bottle gets tossed, and note that, like so many bottles tossed into the sea, this one is ostensibly empty, no message inside—Garrett finally gives the reader the distance from the narrative necessary to truly appreciate the narrative: this was not a story of score-settling among in-laws or indigenous tribes, but, rather, a story about precisely what Garrett said at the outset, Thanksgiving.

My narrator thanked me when I finally wrote him in reply. He’d just been curious, he said, when he’d gone online for the first time in his nursing home library in Texas, and, Googling, had found that someone had written a book about him. Me. My narrator’s name was Louis Belk, and so was his. My Belk was a WWII Army Air Corps veteran, and so was he. My book was (in part) about bomb disposal, and so was his career.

What was the source of your story, he wanted to know? I could have said history. I could have said imagination. I said both. I’d never heard of him before, that much I knew. And so I cited the disclaimer on the copyright page: Any resemblance to persons living or dead…

This much is true. Deep in the Duke University archives, in the first box of the last year of the Garrett papers deposited there, a stack of drafts, notes and research 14.4 inches high—including two issues of National Geographic from the 1930s and some Venezuelan flags—attests to how much time and effort Garrett spent on this final story. It also reveals something else: that he originally titled the story “The Source.” Which makes sense—they were in search of the source of the Orinoco, and we readers were constantly in search of the source of the story.

Garrett’s final choice, “Thanksgiving,” rings better for me, though. Because I’m thankful for his story showing me how controlling narrative distance controls narrative. And thankful for the insight that our characters are always writing us even as we write them. But thankful most of all that, six years after passing him, and two years after his passing, we finally got to talk.

Further Links and Resources:

This essay was adapted from a talk originally delivered at the 2009 AWP Writers Conference in Chicago as part of the panel “Don’t Stand So Close to Me: Controlling Narrative Distance.” Joining Callanan were Peter Turchi, Antonya Nelson, and Christopher Castellani.

Kelly Cherry’s piece, “The Achievement of George Garrett,” is thorough and thoroughly glorious; if you don’t know him, it’s a great place to start.

Cherry was a student of Garrett’s, though she once had to drop out of a class he was teaching. A fellow student then wrote a story about her; then Garrett decided the whole class would; and eventually, one thing led to another and that led to a wonderfully eclectic anthology, The Girl in the Black Raincoat, which features not only that first student’s story, but also one by the girl in the black raincoat herself, and a startling variety of other writers ranging from May Sarton to Mark Strand to Shelby Foote and Leslie Fiedler. As Garrett writes in his introduction, the rules were “simple. All you have to do is have a girl in a black raincoat in your story or poem.” And as Cherry writes elsewhere, “the original black raincoat was a trench coat my mother had found for me in a department store. She certainly never imagined it would end up in a book but was rather pleased to see it.”

The other folks on my historical fiction panel with me that day at UVA were Thomas Mallon, then promoting his book Bandbox, and Robert Kaplow, then promoting his book Me and Orson Welles. I immediately bought both and suggest you do the same.

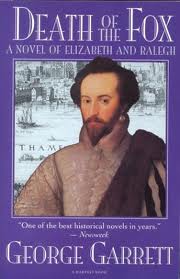

Of course, some people know Garrett best for his historical fiction — in his famed Elizabethan trilogy, Death of the Fox, The Succession, and Entered from the Sun, it’s not just the depth of his research that amazes, but the inventive style in which he presents it.

Of course, some people know Garrett best for his historical fiction — in his famed Elizabethan trilogy, Death of the Fox, The Succession, and Entered from the Sun, it’s not just the depth of his research that amazes, but the inventive style in which he presents it.

And still others know him best as a champion end-of-the-night storyteller. With Garrett gone, that experience is gone, too, but essay collections like Whistling in the Dark come close: pour yourself a drink, pull up a chair, and listen in as he tells decades’ worth of sometimes harrowing, often hilarious adventures in literature.