Quotes and Notes is a monthly craft essay series by Steven Wingate. Steven teaches at the University of Colorado. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008.

Quotes and Notes is a monthly craft essay series by Steven Wingate. Steven teaches at the University of Colorado. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008.

“Always give your characters their best shot.”– Stuart M. Kaminsky

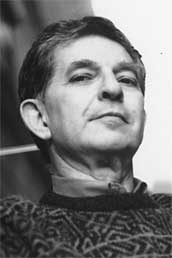

Stuart M. Kaminsky / photo by Jean-Luc Vallet

As a graduate student in screenwriting at Florida State University’s brand-new Film School (circa 1990), I regularly stalked the halls lurking after our MFA program director: the mystery writer Stuart Kaminsky, who just died this past October at the age of seventy-five. In two years of running into him “by chance” in this manner, I never knew Stuart to be anything but all business. The closest he came to letting his guard down was admitting that he liked to write while listening to the music of the Pointer Sisters, which apparently got him in the mood to pen novels such as the Edgar Award-winning A Cold Red Sunrise—part of a body of work that led the Mystery Writers of America to give him their Grand Master Award for lifetime achievement.

“Do you have two minutes?” I’d ask when I waylaid Stuart to ask what he thought of the work I’d given him for commentary. Then he’d look at his watch.

“Thirty seconds,” he’d respond. I had to ask him my question point blank, without beating around the bush, then be prepared for Stuart to do the same with his response. He liked to tell me that I had no discipline, either in my work habits or in the stories I created, and this surprised me because every writing teacher I’d encountered until then had praised me for me discipline. Stuart simply had higher standards for what discipline meant—especially story discipline, the ability to keep your words on the page focused on the core of your story. My time with him as mentor revolved around learning exactly that, particularly when it came to fleshing out character.

“Thirty seconds,” he’d respond. I had to ask him my question point blank, without beating around the bush, then be prepared for Stuart to do the same with his response. He liked to tell me that I had no discipline, either in my work habits or in the stories I created, and this surprised me because every writing teacher I’d encountered until then had praised me for me discipline. Stuart simply had higher standards for what discipline meant—especially story discipline, the ability to keep your words on the page focused on the core of your story. My time with him as mentor revolved around learning exactly that, particularly when it came to fleshing out character.

“Get to know me,”f he often remarked in my margins (quoting Jon Lovitz from Saturday Night Live), with a circle around a given character’s name. Stuart complained that although my characters had plenty of surface texture to them, I never let them act like real human beings on the page. They served functions in my narratives, and when I needed to change the narrative, I could simply tinker with the identity of my characters in order to make them fit the arc better. That made sense to me then—I was young and fantasized about making millions on screenplays. Why pay attention to real characters when they weren’t showing up in the movies around me?

It took a while for Stuart’s approach to sink in, with his “Get to know me” comments and his frequent suggestions to “Always give your characters their best shot.” I took his advice so much to heart that I stopped writing screenplays a few years after grad school and gravitated toward fiction instead, since it gave me more chances to learn about my characters on the page. Though there’s no way to tell exactly what Stuart meant by giving characters their best shot (and he’s not alive anymore to talk about it) I’d like to lay out here what it has meant to me.

When we talk about narrative characters, we mostly talk about objectives and description: what does the character want and what is the character like? Plenty of writing books discuss getting to know characters through the externals: what’s in their trunk, what’s in their medicine cabinet, which friend they would call from jail, etc. It becomes a personality inventory, a list of attributes. I suspect that most writers who have taken a beginning fiction class or worked their way through a how-to book have run into this kind of exercise. The idea is that if we know many, many details about a person, we’ll be able able to make him or her convincing for our audience.

Pinocchio by Enrico Mazzanti

And this may be true. Knowing that Eliza would like to be a pediatric endocrinologist and that she still wears a patch of her old security blanket on her favorite pajamas gives us some understanding of her. She becomes more real to us when we know that she’s still driving a 1976 Ford Maverick because it used to belong to her estranged brother—and still more real if she doesn’t know her own motivation for keeping it. We could add on and on to the external details of the character, trying to make that person real in the way that Pinocchio hopes to become so. Theoretically, we might be able to acquire enough details in a personality inventory for our readers to accept our characters as convincing.

But ultimately, as Stuart Kaminsky knew, this way of creating character doesn’t work because it’s the subtext of our characters’ lives that make them real. Using the “inventory” process to get to know them is fundamentally flawed because it makes us lazy. Robert Boswell, in the title chapter from his excellent book on the fiction craft, The Half-Known World, speaks eloquently against the “inventory” approach that asks such questions as “What is the birthday of the main character” and “What does your character do with his or her free time?” Boswell writes:

The listing of characteristics in advance of real narrative exploration tends to cut a character off at the knees. Such a character may be complicated, but he is rarely complex. Moreover, such characters tend to become narrower as the narrative progresses. A writer who has typed in the answers to the preceding questions may feel knowing, possessively fond, and calmly confident; but he may find it difficult to let the character break out of these imaginative restraints.

Giving characters their “best shot” means, more than anything, encountering those characters as fully developed human beings who can’t be understood—half-known, in Boswell’s terminology—precisely because they are not limited by their attributes. We can’t successfully “plant” the kind of multiple motivations, ambiguities, ambivalences, and revealing self-contradictions that drive our characters; they have to arise out of the situation the characters are in, and the only way we can explore that is on the page.

As writers, we know this. We’re taught this over and over again, but the temptation to make the shortcut is always there. And by shortcut, I don’t mean using a stereotype; I mean going halfway through the process of knowing our characters and being satisfied with letting their surface attributes stand in for their identities. This kind of shorthand happens all the time—for instance, the idea that all characters need “redeeming qualities.” We see this idea in TV and movies all the time, with assassins who donate money to pet shelters or teach the kid across the hallway how to read. This is merely a perversion of true character development, whether it happens with protagonists or bit characters.

“But this person only shows up for two pages,” I’ve heard writers say in workshops. “Does she really have to be developed?” The answer is yes, unless we want to fall into the habit of taking shortcuts. Most of the time when we take those shortcuts, we do it on the mistaken belief that making characters convincing for readers is sufficient. Readers come to fiction not merely to understand who characters are, but to participate in their full, complex, messy lives. When a character steps into our narratives, even for a moment, we owe ourselves and our readers the feeling of a full life entering into the story—of someone entering fully formed, bearing an agenda that is not determined by the course of our narrative or the needs of other characters.

Unfortunately, the person who gets cheated most when an author takes shortcuts and work from a character inventory is the author in question. If our characters don’t have a fully formed life beyond the narrative, our hands will be tied by the function of the character within that narrative and we’ll never be free to really know them. I’ve often wished that Stuart were around to circle a character’s name in my early draft fiction manuscripts and remind me—the way he did with my youthful screenplays—to get to know them better the hard way.

P.S.: Stuart would also tell me, whenever he saw me walking around the FSU Film School with my inevitable mug of coffee, “That stuff will kill you.” I’m proud to say that I’ve now been coffee-free for a full month now—a new record for me. Thanks for the many forms of sage advice, Stuart, and R.I.P.

Further Resources

– If you’re interested in purchasing a book by Stuart M. Kaminsky, remember your local indie bookseller.

– Read an excerpt from Robert Boswell’s latest story collection, The Heyday of Insensitive Bastards, also available at most indie bookstores.

– In this video for Fora TV, Joyce Carol Oates talks about the process of developing realistic characters, using examples from The Gravedigger’s Daughter. To see the full interview, click here–or watch an excerpt below: