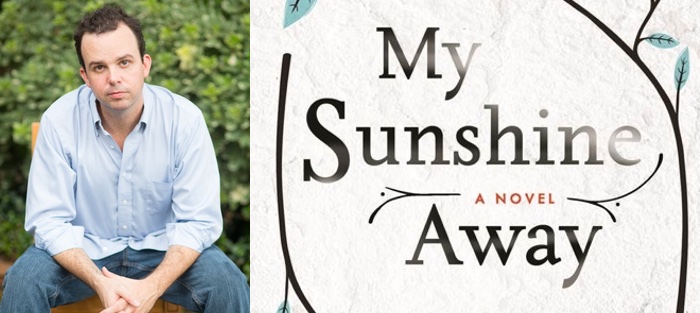

Neal Walsh–you know him as M.O. Walsh–was in the second graduate creative writing workshop I led. He’d come from Baton Rouge via the University of Tennessee and was one of four writers accepted into our brand new MFA program at Ole Miss. He excelled in the program, of course, taking his licks from Barry Hannah, the voice that had drawn him here. While here, he also started our student reading series, serving as emcee for two years before passing that mantle on; the series is now in its twelfth year and flourishing. He also drank in the bars, fished in the lakes, and had great parties. He was an ideal graduate student, generous to his peers, his professors and the town, leaving our program and even Oxford itself better than he found it. Since that workshop, I’ve taught a lot more students. I’ve learned what a lousy teacher I was for Neal. He asked me hard questions I struggled to answer. He pushed me in ways no one had before; he showed me my own weaknesses. And I benefitted from all of the above. I daresay he taught me more, or as much, as I taught him.

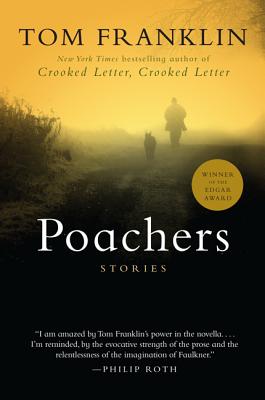

One of the great pleasures of getting older, as a teacher, is seeing one’s students succeed. I had no doubt that Neal would succeed. And when he published his thesis as a collection of stories, as a book, I wasn’t surprised. Just proud. And then he graduated and left town. I’d hear from him, or we’d email, but I didn’t see him as much as I had when he lived here. I knew he was writing a novel, and I was curious, but I had my own novels to write, my children to raise. When I got a copy of My Sunshine Away (G.P. Putnam’s Sons), I was impressed. When I began to read, I was more impressed. The first section ends on a thousand foot cliffhanger, and was wholly unfamiliar to me. This wasn’t the writer who’d published those stories. This was something else. The book had aspects of a crime novel (a rape is central to the plot), a coming-of-age story, a mystery; it’s also a loving look at that under-viewed American city of Baton Rouge and an all-around good story. It’s “literary” in the best ways; that is, its sentences are lovely, but it’s never “lovely” at the expense of plot or pace. It’s my favorite kind of book, where the “commercial” and the “literary” are balanced; it’s the kind of book a John Irving would write, or an Anne Tyler.

But it wasn’t them. It was M.O. Walsh, Neal, my former student. To be honest, it feels funny saying that now, now that he’s a peer, now that he’s one of my favorite writers, now that he’s a teacher himself. I expect to keep reading Neal’s books, and learning from him, for a long time.

Interview:

Tom Franklin: Here we are. Neal has come up from New Orleans, driven almost six hours to be here for this interview. It’s good to see him again. I’m proud of him, and for him, and we’re going to try to interview one another. So, we’ll see how that goes.

M.O. Walsh: That’s right.

One of the first graduate classes I ever taught was at Ole Miss and you were in it, which makes this kind of auspicious.

Yeah, and I remember about that class that you gave us two stories to read on the first day. You said, “Y’all read both of these and tell me which one is good and which one is terrible.” One was “The Birds for Christmas,” by Mark Richard, and one was called something like “Massacre at Christmas.”

It was “Red Christmas.”

Right, about someone killing Santa or something.

Yeah, well, someone kidnapped Santa Claus.

We were all nervous because we didn’t know what you were up to, it felt like some sort of trick question. Then you came back and let us know that the winner, or would it be loser, of the bad story contest was “Red Christmas,” and that it was actually one of your stories from a long time ago.

It’s a terrible story. It’s full of clichés. Mark Richard’s story is funny and wonderful and does everything well and mine did everything terribly. It’s funny you remember that.

I do. All of us thought it was a really cool move to put yourself out there like that. We all looked up to you, had come to Ole Miss to study with you, and the first thing you did was show us how we’re all in it together, how we can all improve. It really kicked us off. It was great.

I also remember a class we had here at my house. We called it Southern Writers. It was four of you, two of you Southerners and two of you Northerners.

Yeah, I still think about that class all the time. We read Barry Hannah, William Gay, George Singleton, Dale Ray Phillips, Rick Bass’s first book. And Lewis Nordan. That class changed how we thought about writing about the South, and writing in general. For me, reading Nordan’s Music of the Swamp (Algonquin, 1991) was just crucial. It was such a huge shift in my writing life. I hope everybody has a moment where they read someone who just seems to give them permission to do with their own writing what they always thought they might want to do, but didn’t know that they could actually do it.

Yeah.

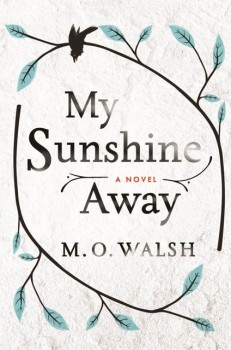

Partly it was Nordan’s style, I guess, that straightforward “There is one more thing to tell” style, but to me it was more about coming out of that Southern tradition where all the white male characters have to be a bad ass rough-and-tumble type of guy. Then, suddenly, Nordan seemed to be coming out of this super sensitive place that felt way more akin to my experience of the South than anything else I’d ever read. I’m actually teaching a similar class right now with two of my grad students, and we’re starting off with Poachers.

Partly it was Nordan’s style, I guess, that straightforward “There is one more thing to tell” style, but to me it was more about coming out of that Southern tradition where all the white male characters have to be a bad ass rough-and-tumble type of guy. Then, suddenly, Nordan seemed to be coming out of this super sensitive place that felt way more akin to my experience of the South than anything else I’d ever read. I’m actually teaching a similar class right now with two of my grad students, and we’re starting off with Poachers.

No kidding?

The idea is to kind of watch the Southern male characters in contemporary literature and see if they are all hitting the same notes, the same get-drunk-and-beat-your-old-lady stereotypes, or if they are evolving at all. And it’s funny, because I’ve been re-reading Poachers, and I guess I’m struck by what a slim book it is, and yet what a great mark it’s left on Southern literature. Is there something you think you did in that book that’s made it last?

I think, or at least I hope, that it had a sort of fresh quality, the way it juxtaposed industry and nature. I love the image of chemical plants on the Tombigbee River. I love the stark manmade beauty of industrial pipes at night. And they are kind of beautiful when you see them at night.

That’s what we see in Louisiana, too, the chemical plants on the water that are actually killing us all. But, at night, when you drive past them, they are like these strange lit-up cities with fires going. It’s complicated. But when you look back at the stories in Poachers now, do you ever see anything you’d want to change, or do you think it’s done? Some people say that stories are never done for the writer but I don’t know if I feel that way.

Honestly, that’s the book I feel best about in terms of it being done. And the reason is this: I worked on those ten stories for about eight years. The story Poachers itself I worked on for over four years. I just went over them each, hundreds of times, so they felt bulletproof. When the editor got the manuscript, he changed one word. In every novel I’ve done, I wish I could have it back because I could totally fix them in places that only I know about. But the stories, no. I might also take out some “was”es. I read one of them recently and I was a little appalled at the wordiness.

That’s crazy. I just re-read them all. They’re not very wordy.

Well, one way that I’ve changed as a writer is I’ve really gotten to where I try not to waste any words. I’ve gotten more economical. I find more beauty in spareness than I ever find in verbosity.

Yeah, but there’s a fine line you have to walk with economy. If you go too spare, to where you have so much pressure on every line, then they can seem to be posing as “meaningful” instead of functional, and that’s just crap.

It can begin to sound precious.

Right. I can remember one time, when I was working on my novel, I got a chance to meet with an editor who had read the first fifty pages of it, and their comment to me was, you need to cut down on all these narrative gestures. What he basically meant was that I had a bunch of one line paragraphs that said something like “It was October and still warm.” He was like, “Big fucking deal. It was October and still warm? Does this need to be an entire paragraph?” And once I saw that one, I saw them everywhere. I was being precious, like everything was so meaningful.

So self aware.

That’s right. But another thing I think about is that a lot of the people that we admire like Cormac McCarthy and William Gay can be pretty verbose.

Yeah, but they aren’t wasting any words. It’s like the Miller Williams quote that I’ll try not to get wrong: “It’s not the unusual word in an unusual way. It’s the usual word in the unusual way.” That’s what has power. Like with McCarthy, “Once there were brook trout in the streams in the mountains. You could see them standing in the amber current…” Standing is such an interesting word there. Standing is not usually associated with fish so it’s specific and strong. Not a lot of adverbs. Like another great McCarthy line, “The dogs were charging them. They were coming very low and very fast.” That’s just understatement.

That’s scary as hell.

It is scary. Because he holds back so much. That’s scarier.

Yeah, and something else I learned from you, that I sometimes find myself telling my students, is that being smart is not the best attribute for a writer.

I couldn’t agree more. I have to believe that because I’m not super smart. Being able to tell a story isn’t being smart. Or even being educated. I think that, for me, storytelling is instinctual and smarts can get in the way of that. I had lunch with a PhD student recently who was taking my class and was thinking of his story the way he thought about his PhD dissertation, applying all these fancy terms to his own work. I said, “You’re not allowed to do that.” Your own writing is different from anything else you read. You’re inside yours. You’re outside of theirs. Just tell your story and don’t worry about what things mean, if the sun’s a symbol for this or that.

That’s a good way to put it.

A question for you. Your stories are very different form your novel in terms of time and style and plot, in terms of even their idea of realism. What happened to you? What shifted? I can remember arguing with you in class. You were writing the strangest stories. So strange that I couldn’t make any sense of them. All the stories in your thesis I could make sense of, but they were not traditional. But your novel is. What brought you from there to here?

I think a couple of things. A lot of my stories are centered around a travelling carnival that went defunct in a small Louisiana town. People who have abilities that are atypical, or people who may be considered freakish. And that kind of predicated a certain weirdness. Plus, before I came to Ole Miss, everything I wrote was very vague and theoretical. I was taking literary theory classes and had Michael Knight as a creative writing teacher who kept saying, “What are you doing? This is the wrong way to approach a story.” I didn’t understand that then. But when I came here, you and Barry quickly showed that to me; that approaching a story theoretically instead from an emotional standpoint is one of the worst things you can do.

That’s true.

Then, once I moved into writing a novel, and had a couple of really oddball novel ideas that didn’t work, I realized it was because I was depending on the wrong things. I was depending on the weirdness rather than the plot or story itself. The far out idea seems great, at first, but it takes a whole lot more than that to sustain a novel.

I think it’s harder to stretch an idea to novel length than it is to short story length. A lot of the more outrageous short story writers have trouble going to novels.

Right. So, part of the problem I’m having now, that I actually want your advice on, is: what do you do after that first novel? I feel torn in a bunch of different directions. After writing My Sunshine Away, not to sound make it sound grandiose or anything, I personally feel kind of emptied out. I feel like I spent all of my energy on it. For seven years, I put everything I had into it. And now the idea that I sit down and start on something else still bothers me. I have a couple of ideas or concepts, sure, but I don’t feel like I’ve found their stories quite yet.

You also had all the time in the world to write the first one. Nobody was waiting on it.

Right. I feel like it’s different, not because I’m worried about the next thing being commercially viable, but because I feel like, “Oh god, now my parents expect it to be good!” Now I realize there is an end result to the process and that people might actually read it and care about it whereas before it was all just me against me. How do you confront that?

I’ll let you know when I figure it out. I’ve not been necessarily smart in the order of books that I write. Poachers (William Morrow, 1999) came out and did well for a collection, then Hell at the Breech (William Morrow) came out five years later, when people had forgotten Poachers. One thing I could have done to help myself is publish it quicker. But I didn’t. And then I published Smonk (William Morrow, 2006), which was a lot weirder and a lot darker, which had a very small readership. And my agent even recommend that I wait to publish it. So, I don’t have a very good track record. But what I found out with Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter (William Morrow, 2010), that is sort of horrifying to me now, and I might be overcompensating somewhat, but what I found out with Crooked Letter is that people respond to characters that they like or can root for, like Vonnegut says. And I had finally written two characters in Crooked Letter who were not wild animals or sociopaths or madmen. And the two people in that book, although you consider that they both may be guilty, are people you can root for, and suddenly that book sold in a way that the others hadn’t. I noticed that. I mean, my father liked Crooked Letter. Normal people liked it. Not just literary people. So, for my next novel, I’m very aware of the fact that I need to deliver characters that people can root for. My instinct is to make them bad, which will somehow make the book more literary, as if my giving you a harder job to like the characters makes me a better writer. But that’s just silly.

Well, anyone that looked at your career from the outside what definitely consider it a success. What would you consider a successful career for a writer?

Well, anyone that looked at your career from the outside what definitely consider it a success. What would you consider a successful career for a writer?

This is going to sound sappy, but I think that if you are happy at it then you are a success. Because it’s so hard to be happy at anything. As a little kid in in 1978, pecking on a portable typewriter, if someone would have told me that one day I’d be making money as a writer and as a professor teaching writing, I wouldn’t have believed them. But, every little comma and semicolon I type back then helped get me here.

I’ve come around to thinking that if a person writes one good book, they’ve done it. Maybe even one great story. If Lewis Nordan had written nothing else but Music of the Swamp, I would have said, “He’s done it. He’s a total success.” Dale Ray Phillips, with My People’s Waltz (W.W. Norton & Co., 1999), is another example. If he never writes anything else, I will always call him a great writer. And I guess what I’ve noticed lately is that the publishing industry thinks, “Well why in the world would someone talented only write one book? Why don’t you keep doing this?” So, I have a hard time squaring that up with the idea that writers can’t just force it. Great books come from some different place.

For me, the ability to approach a new novel, most of it is knowing that I’ve done it before. That it’s possible to do.

See, that’s giving me no peace at all right now. I know I’ve done it, but I don’t necessarily trust that I can do it again.

But you’re in the strange spot of having a successful one behind you. Success may be the worst thing for you. Poachers did well, got me a job and won an award, and they gave me a year to write my next one. But it took me five years to write it because I kind of froze. And, in that five years, I began to collect a list of writers who had a first collection come out and had a novel waiting to be delivered, and that list was long. And so I feel for those people. It’s almost “easy” to spend seven years on a book. Can you be great in two years?

[Laughter.] Right.

I just feel like I am rumbling through the brush with a flashlight and looking for the road. And, I make a lot of wrong turns. But that’s where professionalism comes in. Being professional manifests itself in different ways. You have to be professional and finish a draft. We know a lot of people who are not doing that. People who call themselves writers but never finish anything. Professionals finish the damn book. And professionalism, at the place you are now, means putting all the outside voices aside, any sort of expectation, and doing the work anyway.

Ouch. I know you’re right. Ok, so the question this leads me to is: Now that you are going from one book to another, is your joy from the writing process changing? Is the hunger different?

Every answer is cliché. It’s a different kind of hunger for me now. Back then it was a hunger to get in the game, to make the major leagues. Then it becomes a hunger for different things.

To push that metaphor, now that you’re in the major leagues, do you want the biggest contract on a given year, or do you want the hall of fame?

You want both. But, you know, you may not get either.

But you want both.

Yes.

When I was writing stories in college, I got the biggest kick out of staying up all night and just making shit up. Now, though, I get zero pleasure out of the blank page, out of that first draft. I get a huge thrill out of revising, though. I’d much rather go to three sloppy paragraphs and tinker with them then I would write three new sloppy paragraphs. So, I guess my question is: Am I doomed?

No. I find joy in exactly that same place. I do find new pages harder than I used to. But once I’ve got something down, I can handle it.

I think writing a new novel sounds terrifying because I’ve realized what a long process it is and how everything I put down needs to be good not only now, but three years from now when I’m later dealing with it in the plot.

Because if you screw something up in a novel, you might have to redo the whole thing.

I guess there’s nothing I would rather do than have two lives. One in which I write a horrible first draft in my dreaming life, and then another real life where I can wake up and fix it.

Well, where professionalism comes in is writing a lot of bad shit.

I heard Mark Richard at a conference one time, where he said, “An amateur writer has a hundred pages of the most beautiful novel ever written sitting unfinished in their drawer. A professional has total piece of shit that is finished and they are willing to make it better.” That really stuck with me because, at that time, I had a hundred and fifty pages of a novel sitting unfinished on my computer. [Laughter.] That leads me to another question: Who is working now that you are truly excited about the next thing they finish? Who are you like, “I cannot wait to see the next thing they do.”

Stephen King.

That’s amazing

I love his books. I read them all. He’s just getting better.

That’s actually who got me reading in the first place.

Also Richard Flanagan. Two totally different reading experiences (King and Flanagan) but both totally enjoyable. One is like a fine and prim meal, and one’s like gobbling fast food. I love them both. And, honestly, I’m excited to see what my students do; like you and Sean Ennis and Jacob Rubin and Alex Taylor. And I’ll say this to you, not just kissing your ass for this interview, but I read your novel with more excitement than anything I’ve read in a long time because it was you, but then because it wasn’t you. I kept forgetting that I knew you and kept getting lost in the spirit of that novel and the voice. And that’s a really cool thing. It gives me chills. See? [Leans over to show goosebumps on his arms.] To forget that it’s my friend that wrote it; that it’s instead something new. But, yeah, seeing my students publish well. It’s a really cool set of emotions.

Thanks, man. OK. Another question. Teaching workshops sometimes makes me feel like a machine gun of advice. I feel like I’m supposed to have answers for every problem that comes up in a person’s story, and I obviously don’t have that. So, I guess what I’d want to ask you is, out of all the million pieces of writing advice that you’ve heard, what really sticks with you?

Yeah, one teacher whose advice really stuck with me was Bill Harrison. He wrote Rollerball (Warner Books, 1975), which turned into that great movie. Bill has a lot of soundbytes that really got to me. He’d say things like, “Only write in first person if the voice demands to be heard.” He’d say, “Every opening of a novel or a story is a contract between the writer and the reader.” He said these things that were memorable one liners that I truly believe now. He’s always in my head. And then I also saw the way Donald “Skip” Hayes worked with stories. He dispensed really practical advice about how to fix workshop stories in ways that everyone could use in their own stories, too. That’s what I think the ideal is, to be able to make every workshop a craft lesson.

One thing that sticks with me is a piece of ridiculous advice that Barry Hannah gave us, which is not even really advice, but he said, “Writing is easy. All you have to do is have something really exciting on every page.” [Laughter.] That haunts me because I know I’m not doing that, but he found ways to do it in the language, especially in his stories. He always had something exciting around every turn.

No kidding. His stories are sprints. He’s writing like hell. It’s hard to do that in a novel, though. Padgett Powell comes close with The Interrogative Mood (Ecco, 2009), I think. What an insane idea for a novel.

I guess I also think about that advice about “being exciting” when it comes to the hard part about writing a novel, which is doing all the necessary grunt work of having people walk into a room or drive to a store in order to get them to the next plot point, but to also make that sort of mundane stuff engaging and interesting and clear through the language. That’s key. You can’t take those scenes off. You have to find a way to make them interesting.

One thing I’ve found about novels versus stories is that stories are easy to start and hard to finish and novels are harder to start and easier to finish.

Yeah, once I figured out my novel, I started running toward the end. That felt like joy.

E.L. Doctorow says writing a novel is like driving at night with your headlights on. You can only see what’s right in front of you. You make your way as an act of faith.

Damn, that’s a good analogy.

I know. Part of my problem is that I can’t imagine the events of a novel beforehand. They have to unfold before me. Most of my action comes to me as I’m pecking on the computer. With Crooked Letter, I didn’t even know the major thing until very late in the process. I didn’t know who the damn killer was. If you were tracking it like an A to Z line, I was probably at W before I realized who had done it.

That’s insane.

I know. But I learned from it. I do think with every novel we learn something that we can use as we move forward.

One thing I hope I learned from my book is the importance of chapter endings; that the end of chapter has to make you desperate to read the next chapter. That is its primary function. Even if you are going for a nice internal moment or emotion, the chapter has to make you hunger for the next one and harken the reader back to the entire reason they are reading the book in the first place.

I agree. Not enough books do that.

OK. So, in terms of writing about the South; lately, I’ve become obsessed with the sort of fine line between a genuine interest in the South and some sort of fetishism or cute study of it. I’ll read some books about the South that I don’t like at all, because I feel like they are lampooning it, yet they are equally as praised as other books that I think are doing it justice. Some of them feel like they are making fun of their characters or playing on stereotypes and others are just observing their characters. Yet I don’t see a great difference in the critical responses to what seems, to me, like two very different attitudes about the South. One is “above” it and the other is “from” it. Does that make sense?

Tony Earley has a great essay about how “Why I Live at the P.O.” by Eudora Welty ruined Southern literature. It’s about how all her characters appear on the surface just to be eccentric and strange, although there’s a lot more going on in that story than it gets credit for. But Earley says that Welty makes it looks so easy that now we are all writing stereotypical characters, and that, basically, we should be ashamed of ourselves. And I see that, too. I get real tired of all the “maw maw” and “daddy’s” I see in Southern lit. I take his point.

I feel very conscious of that. There’s so many clichés in Southern Lit. That could be another interview in itself. So, I wonder, where does Southern Lit have to go? Where do you see us moving?

It seems that a lot of us move back in history. McCarthy does that a lot. William Gay does it.

Is that just because they are afraid of the smart phone? [Laughter.]

The smart phone has definitely changed things. It’s changed plotting. Because nowadays a character can always make a call. So, you have to put them in a dead zone.

Or the phone has to fall out of the car and get lost or something.

Right. But that’s getting harder to do. I recently read a story where a person left their phone at a hotel and I didn’t buy it. Nobody leaves their phone anymore.

Do you feel that technology is, in some ways, a danger to traditional narration?

No. Of course not. Good writers find a way to incorporate everything naturally. Stephen King has no problem with it. He has characters that use Google to find things and he does it beautifully. But, you know, if it’s a problem, you could always set something in 1998.

I do wonder if we’ll see even more historical fiction coming out, though, as a way to get around these things.

Yeah. Or people go to the ruined future, where all the satellites are down and the world is covered in ash.

Is that maybe what all fiction is? Are people just trying to find a way out of where they actually are?

Probably. Things are pretty fucking miserable now. Let’s look forward or back. Let’s get the hell out. Any place but here.

Any place but here.

There’s a title for the interview. I think there’s the ending.

I think so.