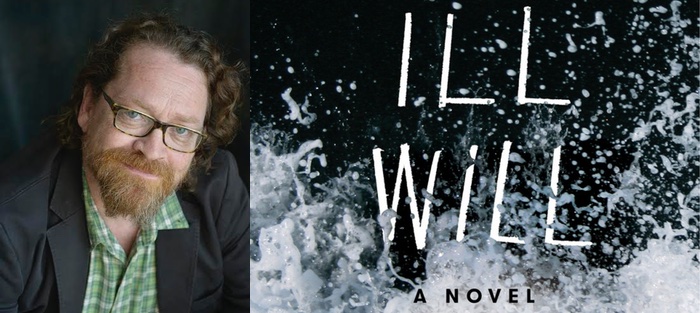

Near the end of graduate school, one of my instructors said, “You’re great with character, but you don’t know anything about structure.” That was the first time I remember hearing the word in two years. Many people had said it, no doubt, or its sister words (i.e., shape, order, form), but I hadn’t heard it. Or I hadn’t understood its significance. This is the power of being told you are bad at something: Finally, I paid attention. Since graduating, I’ve been on a mission to figure out structure, and one of my great teachers has been Dan Chaon.

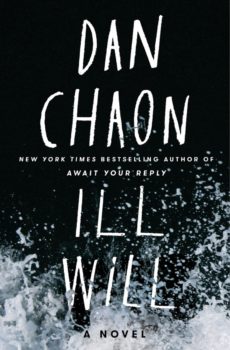

It didn’t surprise me to come across Celeste Ng describing Chaon’s new novel, Ill Will, out this month from Random House, as a “dark Mobius strip of a thriller,” or Publishers Weekly saying, “With impressive skill, across multiple narratives that twine, fracture, and reset, Chaon expertly realizes his singular vision of American dread.” He edged into the territory of literary thriller with his first novel, You Remind Me of Me, and fully claimed it with his second, Await Your Reply. In both, Chaon wove multiple storylines together to create page-turners with emotional depth and complexity, but what truly sets his work apart is the way he defies chronology. Because we live our lives forward, in chronological order, we think of our emotions as being a product of this cause and effect, but Chaon somehow upends all of that, and in doing so creates devastating emotional resonance. The manipulation of time in both novels engages his readers in a journey that is at once both more deeply connected to and completely different from the characters’ journeys. As I read, the word “patchwork” came to mind, and when I spoke to him about the structure of his books, he offered “hopscotch” as another metaphor.

In addition to his novels, Chaon has published three story collections, including Stay Awake (2012), a finalist for the Story Prize, and Among the Missing, a finalist for the National Book Award. He has also been the recipient of an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a finalist for both the National Magazine Award in Fiction and the Shirley Jackson Award. His fiction has been reprinted in The Best American Short Stories, The Pushcart Prize anthologies, and The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories. Chaon teaches at Oberlin College in Ohio and was gracious enough to give me hours of his time via video chat from his writing attic in Cleveland.

Interview:

Amy Gustine: In reviews of your work people talk about it being dark, but that’s not what I walk away with. I walk away with the incredible honesty and authenticity of the characters’ emotions.

Dan Chaon: Part of it has to do with people’s concept of what constitutes a happy ending. That has something to do with how time works in the novels because in a lot of cases things end in a place where you kind of know that things aren’t going to turn out as well for the person as they’d hoped. I think of the end of You Remind Me of Me because you end with Nora being hopeful and you’re like, “Oh, this is so sad.” It’s important to remember that we’re in this continuum.

How did you decide to present Nora’s events in the order that you did? Did you lay that out ahead of time, or did you feel your way through it?

I don’t really lay things out ahead of time, but with both novels I knew I was going to do a hopscotch pattern in the way that I dealt with the individual sections, and once I figured out how to do that, it was a way for me to plot the novel. As short story writers I think a lot of us really don’t have any idea what a novel is going to be like, and I had written two short story collections before I started that novel, and my first draft was disorganized, lots of summary, very little scene, and my editor said this doesn’t resemble your stories at all. I went back and thought, I’m going to try to do these chapters like they’re individual stories. That was the thing that helped me figure out how to write a novel, this idea that I could do chapters like a series of interconnected stories. Then trying to figure out how to balance those multiple points of view was really a way to figure out what’s going to happen next, so Nora became one of the points of view. As I was going along I was learning her story and it became the counterpoint to the other stories. The way that I write I really don’t know a lot when I start out.

I don’t really lay things out ahead of time, but with both novels I knew I was going to do a hopscotch pattern in the way that I dealt with the individual sections, and once I figured out how to do that, it was a way for me to plot the novel. As short story writers I think a lot of us really don’t have any idea what a novel is going to be like, and I had written two short story collections before I started that novel, and my first draft was disorganized, lots of summary, very little scene, and my editor said this doesn’t resemble your stories at all. I went back and thought, I’m going to try to do these chapters like they’re individual stories. That was the thing that helped me figure out how to write a novel, this idea that I could do chapters like a series of interconnected stories. Then trying to figure out how to balance those multiple points of view was really a way to figure out what’s going to happen next, so Nora became one of the points of view. As I was going along I was learning her story and it became the counterpoint to the other stories. The way that I write I really don’t know a lot when I start out.

In Await Your Reply, what made you write about George and Hayden in the first place? Were you originally energized by this idea of identity theft in general?

I originally thought they were much more separate but that they were connected by mood. I originally though that I was going to create a scheme that connected all of [the characters], that there was going to be some sort of Hitchcockian MacGuffin that brought them all together. One of the things that makes me write is the stress of needing to figure out how things are connected and I trust my subconscious that it’s eventually going to come out, which can be very, very scary. It requires a lot of rewriting in the second draft. I’m very much a second draft person. Await Your Reply and You Remind Me of Me were both pretty messy in the first draft form and a lot of the tightness and the organization came in the second draft.

In Await Your Reply you open up with Ryan on the way to the hospital and he’s already lost his hand. The next time we see Ryan, however, it’s prior to his hand being cut off. At one point did you arrive at that presentation?

That actually was the first thing that I wrote. I had this image that I wanted to write about which was a dad and his son driving to the hospital and his hand in the cooler between them and then a lot of the novel was trying to figure out how did that happen and how do I get back there.

That actually was the first thing that I wrote. I had this image that I wanted to write about which was a dad and his son driving to the hospital and his hand in the cooler between them and then a lot of the novel was trying to figure out how did that happen and how do I get back there.

In You Remind Me of Me, Nora’s last chapter takes place at a time that’s earlier than much of the other events we hear about from her point of view. Did you write Nora’s story in the sequence we read it or in the order Nora would have experienced it?

No, that chapter was actually the last thing I wrote. I guess I knew that the book would start with Jonah’s death and end with his birth. I knew that Await Your Reply would start with the hand getting chopped off and wrap back around to how that happened. I knew that was the structure. With the Nora section I knew that all the emotion of the book was centralized there and that’s when that chapter came out. It was like the end of a short story—you kind of know there’s going to be this lift, the music will start to swell and there’ll be this thematic thing that rises up in you and it’s the same sort of feeling that happens in writing a novel.

In The New York Times review of You Remind Me of Me Sara Mosle said: “Adult knowledge shades in the outlines of limited youthful understandings, adding depth perception in a kind of narrative foreshortening. Chaon’s previous writing had this backward-glancing quality, but in You Remind Me of Me he dispenses with sequential time altogether, introducing his characters as adolescents or even adults before we see them as children and connecting seemingly disparate moments in an unerring emotional chronology.” I started thinking it’s not the characters’ emotional chronology because they don’t experience things in the order we do. It’s the readers’ emotional chronology that you’re doing there.

And the writer’s too. There’s an interview with Alice Munro in which she talks about her stories being like a house with a lot of rooms you can wander through, that she’s building stories as architecture and that really stuck with me, the idea that when you’re building a story or character, chronology isn’t the only or main way we experience the world. If you want to put somebody’s life together starting with birth and ending with death it is not necessarily the best way to describe who they were.

But it seems to me you’d have to proceed with a kind of faith and instinct on these things and, as you say, look at what you produce and be open to rearranging it. That’s why I was curious what order you write things in.

Part of it’s intuitive and that may be because I’m intuitive and I think story writing tends to be intuitive. I’ve never outlined a story before and I’ve never outlined a novel until the second draft. You’re kind of trusting that you’ve got this structure and I’m going to write Jonah, then Troy, then Nora and I’ve got to go back to Jonah again so where am I going to land in his life? Or what am I curious about? That was really the structure of the writing of it and it tended to stay the same once I was doing the second drafthings tended to stay where they were when I first wrote them. There were places where I just had a place marker. That was especially true in Await Your Reply, where I had to go back, say, to Lucy, but I’m just going to leave that chapter blank and go on because I don’t know what happens there. I guess I do have an outline in that I have this blank structure to fill in. Which is kind of like a game, but I really like working that way.

I like the way that approach allows you to dip into these important moments and not spend time getting us from one important moment to another.

Again, that’s very much a short story writer’s trick. I don’t feel like I could really write David Copperfield. That’s beyond what I would ever want to take on. The other thing about that kind of structure is that it can give you a certain rhythm. Pacing is important to me, the way things move from moment to moment. You asked me about chapter lengths.

That and section breaks. In the beginning of hapter six in Await Your Reply you’ve got a three-sentence section.

I think it has to do with creating a certain kind of rhythm, or momentum. In some ways it has to do with the fact that I was a filmmaker and I feel like some of the rhythm stuff is influenced by film and TV. I think Await Your Reply was particularly influenced by serial television like The Sopranos and Six Feet Under where there is this jump between characters and these very short moments, and we’ll later get back to them.

Which is something you’ve seen a lot more in modern literature. If you go back to an Edith Wharton or George Eliot you don’t see that.

I think that readers who aren’t familiar with that device, readers who have been reading more traditional structures, are really confused by it.

I think that readers who aren’t familiar with that device, readers who have been reading more traditional structures, are really confused by it.

I found that I was never confused. As a writer, I’m looking at it like—that’s interesting, how did that affect me? Sometimes it’s obvious: It was a brilliant way to shift the tone or place. Sometimes I think it’s the way it puts stress on the last sentence in the section when you break it.

That’s again a short story trick and a poetry trick, where you put this kind of stress on the last moment in a chapter that gives it a certain kind of resonance that will carry through. Some writers, particularly pulpy writers, will use those chapter endings as cliffhangers. That can be really useful. You look at the Harry Potter books or Dan Brown and they are pretty short chapters that almost all end with cliffhangers. That can be a super effective device.

Can you think of anyone else who uses achronology, this “hopscotch,” quite like you do?

I think A Visit rom the Goon Squad uses achronology quite radically. Some of the David Mitchell stuff, but that’s a little bit more out there. Cloud Atlas, Ghostwritten, The Bone Clocks. Cortzar’s Hopscotch. Cortzar’s a super big influence on me. I want to say The Counterfeiters does that, the André Gide book.

Your tone is different to me.

Oh yeah, very different. I tend to be doing these things that are broad in their structure but they’re more intimate in their approach to character.

I feel you have a kind of intimacy and closeness with these people as real people.

Yeah, even though the structures tend to be very artificial.

And yet I never felt that it overpowered the intimacy. Sometimes when you use a nontraditional chronology it starts to call so much attention to itself as artificial that it takes away from the emotion.

That’s kind of the effect that you get from Gone Girl. The Lauren Groff book, Fates and Furies, kind of does the same thing, but it feels a little less calculated.

There’s something about the language. She glosses kind of raw, nasty emotions in an elegant style. I like your more raw style. Hers didn’t feel as much of a realistic character portrayal as yours does.

Groff? It depends on what kind of emotional effect you’re after. For me one of the things that I’ve always been after and always been curious about is taking extreme emotions and people who are not traditionally heroic and finding what’s human about them. I think it requires a different kind of approach to character. I don’t feel like that’s what Groff is after. She’s sort of after the opposite. She’s taking ordinary nice people and finding what’s awful about them.

That’s a great way to think about it! Let’s talk a little bit about your verb tense. In You Remind Me of Me some of the chapters are written present tense and some are in past. And it’s not consistent. It’s not that Troy is always past tense and Jonah is always present. It varies. I was curious if you could speak to that a little bit.

I’m not doing this in a grammatically correct way at all and I had to wrestle with the copyeditor when it came time to figure this out. It has to do with how filmic I imagined the scene would be. Is the scene being recalled from a distance or are we watching it as it’s happening? I’ve always been aware of when people switch tenses when they’re telling stories. There’s a big difference between someone saying, “I was walking to the store yesterday” versus “Okay, so I’m walking to the story yesterday.” It’s just a difference in the way you engage with the moment. I’m really interested in that as a storytelling effect. Sometimes it’s important to have the story being recalled and some times it’s important for it to be in the moment. My editor for You Remind Me of Me, Dan Smetenka, really helped me with that. When I first wrote the beginning of You Remind Me of Me I’d mentioned that Jonah had these scars and that he’d been attacked by a dog, but the first chapter didn’t exist for quite a while.

Which has to be one of the most harrowing chapters I’ve ever read and one of the finest descriptions of a dog, just physically of the dog. I mean, it’s fantastic!

Dan was like, “We need to see this dog attack,” and that ended up being the first chapter.

I remember specifically when Troy is arrested—he’s already been arrested and you’re learning about the arrest in the past tense. I just loved the switching of verb tenses there, but I didn’t notice it until I sat down to analyze the book.

I’m glad. You shouldn’t.

Can you give us a little hint about the new novel?

It’s another multiple point of view book. It starts out with a guy whose family was murdered when he was a kid and his older brother went to prison for the murder and then at the beginning of the novel, twenty years later, the older brother is released based on DNA evidence that proves he didn’t do it. So it’s a thriller about what really happened and about how the changes in the past and the changes in what’s true and what’s not have destroyed everybody in the present.

Tell me a little bit about this whole flashback vs. achronology. It’s sort of hard to explain…it’s a subtle textual thing.

When you are doing a flashback, you are contextualizing it in a moment. Usually what happens is that you create an occasion for it, like someone standing looking out a window and as they look out the window they remember, so there’s that actual sense of plunging. But also I think flashback has more subjectivity to it, that it’s more unreliable than when you’re putting it in a filmic present moment because flashback is always filtered. You always have that dual point of view.

And even if you aren’t dealing with an unreliable narrator, there’s a sense that this is a memory and memories are slightly unreliable by their very nature.

Right, I think it does and particularly in my work where so much of it is concerned with unreliability and lying and self-deception. Maybe a distinction between those two things is very important.