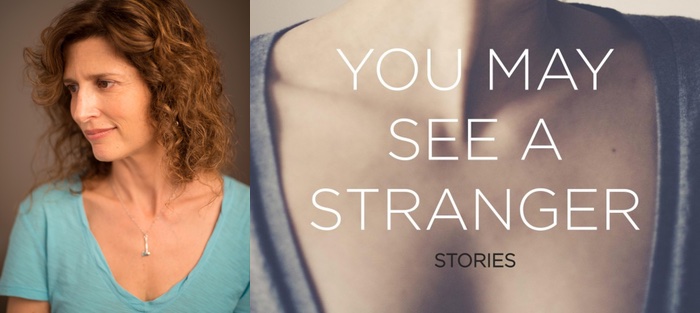

Imagine being introduced to yourself at a bubbling cocktail party. You’re wearing your best suit. You’re on your second drink. Would you immediately recognize you? In You May See a Stranger, Paula Whyman’s debut story collection from TriQuarterly Books, Miranda Weber finds pieces of herself that don’t always seem familiar. She self-sabotages her love life. She’s raw and reeling from break ups, makeups, and sibling struggles. She tries to fix problems with sex. She overthinks her missteps. During a driver’s education course, Miranda Weber’s desire awakens. Following a suicide, her darker thoughts about the true nature of happiness prevail. After an encounter with a crackhead, she understands the daily nature of terror. Through these linked stories, one woman navigates a path to identity. She doesn’t always like what she finds, but her observations are clever, sharp, funny, and always insightful.

Paula Whyman has published stories in Ploughshares, McSweeney’s Quarterly, Virginia Quarterly Review, and other journals. Her work has been supported by fellowships from The MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, The Studios of Key West, and VCCA, and she was awarded a 2014 Tennessee Williams Scholarship in Fiction by the Sewanee Writers Conference. You May See a Stranger is her first book.

Paula and I are both active literary citizens in our D.C. community. We see each other often at readings at Politics and Prose; we toast at book parties; we chat about emerging and established writers we admire at PEN/Faulkner Foundation events. For this interview, we met up for coffee at Paula’s office in Friendship Heights.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: We share a connection with American University. I’ve been teaching College Writing and Creative Writing there for five years. You earned your MFA at AU after eight years in editing. Why did you decide to enroll in an MFA?

Paula Whyman: My background is as an editor—I worked as an editor for different types of publications for eight years before entering the MFA program. I enjoyed being an editor, but I had little time left for my own writing, and after awhile, it became clear that I needed to give myself that time. It was a good decision. In addition to that time, two other elements were crucial: It was very much about developing critical judgment. That was hugely important. I thought I knew when other people’s work needed work or didn’t, but I didn’t really know when my own work was going well. I was hypercritical of my own writing—I suppose I still am!–but I had to learn to be so in a way that was useful to my work. And then finally, it was about finding a community. Not unlike what I discovered later going to artist colonies–the importance of commiseration! Of being around people who are facing similar problems in their creative work and can support each other even as we’re all working in isolation. It can be as simple as recognizing that zoned-out look that artists have when they’re in the middle of a creative project, there but not-there—it’s great to be around people who know what that’s about.

What led to the decision to publish You May See a Stranger with TriQuarterly Books?

My book was making the rounds, but no one had made a solid offer yet. It was a weird sort of coincidence, in that I’d been invited to attend Sewanee as a scholar, and I hoped to meet editors there, like Mike Levine, TriQuarterly’s editor. I knew they had a great reputation and an impressive list. A few weeks before the conference, Mike called me out of the blue after reading my scholar bio on the Sewanee website. My agent sent him the manuscript, and Mike said he’d try to read some of the collection before the conference. Then Mike and I met at Sewanee, at French House one night after the evening’s readings. Over a glass of George Dickel, he told me he wanted to publish my book. He’d only had time to read a few of the stories, but he said the voice was unique and special. I didn’t believe him. Because I’m like that. I said something like, Why don’t you read the rest of the book first, just to make sure? He said he didn’t expect to change his mind. And yeah, obviously, he didn’t…

It’s a gorgeous collection. Let’s talk about what keeps Miranda’s “hot mess” intact, therefore linking each story. There is a linear progression from Miranda’s sexual awakening through her sorting of her own identity. Unreliability and the shifting nature of reality are her norm. In “Self Report,” you write “She had thought that time and experience made one’s impressions more accurate, but in fact what age and experience had taught her was that there were no reliable impressions” (192). If age and experience aren’t reliable, what is?

I think Miranda, as she ages, is realizing that people are far more complicated than she thought when she was younger, that objectivity is hard to come by, and she’s not where she thought she’d be in her life. Maybe she wonders if it’s like that for everyone. The problem at hand in this story is highlighting her own dissatisfaction. As a teenager, perhaps Miranda had thought, as many of us did, that adulthood would bring some sort of secret knowledge. Well, at least for her, the secret knowledge is that people are often unpredictable, unfathomable–not least, perhaps, her own behavior.

I think Miranda, as she ages, is realizing that people are far more complicated than she thought when she was younger, that objectivity is hard to come by, and she’s not where she thought she’d be in her life. Maybe she wonders if it’s like that for everyone. The problem at hand in this story is highlighting her own dissatisfaction. As a teenager, perhaps Miranda had thought, as many of us did, that adulthood would bring some sort of secret knowledge. Well, at least for her, the secret knowledge is that people are often unpredictable, unfathomable–not least, perhaps, her own behavior.

The narrative observations are most acute when Miranda is reflecting on her complicated relationship with Donna, her disabled sister. Sometimes Miranda feels sympathetic, mostly she’s annoyed, and she’s always obligated. Did you struggle with this characterization?

I was worried about making Miranda unlikable in the way she behaves with her sister at times, the way she feels about her. But I think these are real feelings, and she would have the whole range of feelings in this situation—the anger, the lack of control of her future—Will she be responsible for caring for her sister? The guilt about feeling this way, and with all of that, the deep love for her sister. Anyone who has grown up with a sibling who is in some way disabled knows what this feels like. A wonderful novel dealing with this complicated sibling relationship is Akhil Sharma’s Family Life, in which the protagonist’s older brother has a life-changing accident that renders him unable to care for himself. I read the book recently, and I felt that Sharma captured everything about that relationship perfectly.

Really? I was hoping we’d finally moved on from needing female characters to be likeable. Damn it. I enjoyed her edges. She’s real. Brutally honest.

I’m glad to hear you say that. Whether Miranda is, at times, “unlikeable”—it wasn’t even conscious, really, it was just, this is who she is. What do we even mean by likeable? It’s a subjective judgment. As a reader, I prefer a protagonist with some edges, as you say. I love to read characters I think of as interesting train wrecks. What’s important to me is that the humanity of the character comes across. And of course it bugs me that people mostly seem to ask this question about female characters. Why? That ingrained notion that girls are supposed to be “nice”? Even if it’s unconscious, that bias still seems to be with us. Thinking of the male protagonists I’m drawn to, they’re not likeable—I mean—Portnoy? But how many people say, ‘Portnoy isn’t likeable, why would I read that?’ Maybe they say that about Mickey Sabbath, but I disagree—I find him sadly sympathetic, very human. I think especially of Roth’s protags, I suppose. But for god’s sake, is Olive Kitteridge likeable? Jeez, who cares. She’s complicated and fascinating. One of the most fascinating protags in contemporary fiction, IMO. Is unlikeable also unsympathetic? I don’t think so. I think we have to feel something for the protag in order to keep reading—and it can be shock or disgust but also some fellow feeling, which we may initially resist. I’m also thinking of the Patrick Melrose books by Edward St. Aubyn. I’ve read the first two so far, and the second one challenges the reader’s sympathies for Patrick, but it’s his humanity, our understanding of his past and the basis for his bad behavior, that breaks through any resistance.

All of that said, when a couple of these stories first appeared in journals, I did make a few edits to tone Miranda down, in response to editorial feedback—from women, which was interesting to me.

In “Just Sex” Miranda is ambivalent about many of the facets of being a woman, specifically about motherhood. “I understood in that moment, seeing Kim gradually inch toward the edge of her seat again, that if you were a mother, you were always waiting for the next time” (192). Surely, this coincides with her own experiences watching her mother wait for Donna’s next shoe to drop and it does.

That’s possible. I love it when readers point out connections between the stories I haven’t considered! I suppose I don’t make the connection explicit, like, say, in Munro’s linked collection The Beggar Maid, the Flo and Rose stories, which are about the relationship between a woman and her stepmother, the way Rose is always reacting consciously or unconsciously in opposition to that relationship. That’s another book I love, which I didn’t read completely until after I wrote this collection.

That’s possible. I love it when readers point out connections between the stories I haven’t considered! I suppose I don’t make the connection explicit, like, say, in Munro’s linked collection The Beggar Maid, the Flo and Rose stories, which are about the relationship between a woman and her stepmother, the way Rose is always reacting consciously or unconsciously in opposition to that relationship. That’s another book I love, which I didn’t read completely until after I wrote this collection.

On the other hand, Miranda is still pretty young in that scene you describe, and I think she may not be mature enough yet to fully see her mother as a separate person and the mother of a disabled child. I think she does understand this later on. But at this point, I think she’d be reflecting more on how her mother felt watching her rather than her sister. When you grow up in a family where there are “issues,” you don’t necessarily notice it. It can all seem normal—it’s all Miranda knows, so it’s her normal—until you’re well out of it, I think.

Sex, power, and politics are binding themes in You May See a Stranger. Little of this is romantic. Some of it’s even clinical. How do you write sex so well?

Thank you! I try to stick with what is unique to these characters and their situation, to include only what’s absolutely necessary to convey to the reader what’s going on and what’s important in the scene, what’s different here because of who these characters are. I try only to include a sex scene if it’s important to the story. Maybe that’s not any different than writing about, I don’t know, bowling. I wouldn’t write a scene where the characters are bowling, or having sex, or, um, both, unless it illuminates character and, I hope, advances the story. Plus, you can get too caught up in the moving parts, and then it’s boring or unintentionally funny. I skip a lot of the mechanics unless I really want to push the humor. Let’s face it, the mechanics are humorous. In his book Sam the Cat, Matt Klam referred to “wiggly meats,” I believe. That about covers it.

Miranda doesn’t always seem to enjoy sex.

That’s true. There are all kinds of reasons why Miranda’s in various sexual situations in these stories, certainly not all about love or even lust. So it’s not surprising that sometimes she doesn’t enjoy it. I wanted her reactions to be as real as possible. I don’t know if I succeeded, but that’s what I was going for. I mean, does everyone enjoy sex all the time?

And she regrets some of the relationships.

I think regret indicates that you’ve learned something, so I think that’s a hopeful sign. When I visit students through Writers in Schools programs in New York and D.C., I often teach the story “Drivers Education”—that’s the first story in the book, one of the stories in which Miranda’s a teenager—and one of the questions I ask is, what do we know about Miranda’s judgment from that story? Mr. White, the driver’s ed teacher, lectures on judgment. He’s talking about driving, but not only that. What role does judgment play in the story? What role does it have with this narrator? When you see the end of that story, what does that mean for Miranda’s future? Miranda’s life circumstances have changed, but what about wisdom? I’ll let the reader decide.

I can see that. You May See a Stranger is really the story of Miranda’s self development, right?

Yes, I think that’s true. I hope that’s true.

What stories or collections or writers influenced your work, especially as you were figuring out the connections among the stories?

Definitely Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout, especially for the way it follows the characters over the life span. I like that Olive is a regular person, a difficult person. I like the way we see how things turn out for her, how she grows, or doesn’t. That book is told from more than one point-of-view. I couldn’t really find a model in which the stories were told by only one character and in chronological order over a long period of time. I’m sure such a book exists, though, and I’d very much like to read it. When I’d finished writing You May See a Stranger and I was thinking about the connections among the stories, I read Alice Munro’s The Begger Maid. I’d read a few of the stories out of order before, but had not read the whole book at once until then. Of course Munro is one of my idols. She and Lorrie Moore and Ann Beattie. I read a lot of novels while I was writing this book, though. Maybe that’s why I ended up with a sort of novelistic arc and connectivity among the stories, and a single protagonist for all the stories.

What are you working on now?

One thing I’m doing, I’m collaborating with composer Scott Wheeler to make a music theater piece out of the story “Transfigured Night.” I’m adapting the text for the stage. I’ve never done that with one of my short stories before. It forces me to think about storytelling in a different way, how to convey what’s important without all the interior stuff. It’s a challenge. I’m enjoying it. And actually, when I was a kid, I made up plays before I wrote stories, so it’s not completely unfamiliar.

I’m also working on a novel. I don’t want to say much about it, because when I talk too much about something, it feels like I already wrote it, and then I lose interest, but I’ll say that it’s set in D.C., like Stranger. I’m about halfway through a draft. I know what the “big event” is, and I’m figuring out the rest as I go.