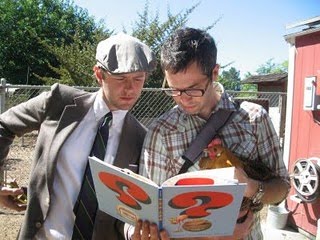

Mac Barnett (left) and Adam Rex (holding the chicken) read from their book Guess Again! Photo via Barnett and Rex's blog Guys With Books

Mac Barnett is one of several promising authors who are redefining and reaffirming what it means to write for children. Not satisfied with pat definitions of “kid friendly,” Barnett inherited the charge to nudge children’s literature tropes in new directions from his friend and mentor Jon Scieszka, author of The Stinky Cheese Man. Barnett, the former director of 826LA, a non-profit writing center for children, writes on the border between humorist and absurdist. In his first picture book, Billy Twitters and His Blue Whale Problem, illustrated by Adam Rex, a boy’s bad behavior is punished with, of all things, the gift of a pet whale. Barnett and Rex’s second collaboration, Guess Again!, offers surreal solutions to standard guessing-game clues. Someone with “floppy ears” who “steals carrots from the neighbor’s yard” is not the usual suspect, but rather, “Grandpa Ned.” Given his experience and passion, it is not surprising that Barnett helmed a “A Picture Book Manifesto,” a proclamation written by Barnett and signed by nearly two dozen other picture book creators that challenges children’s authors to never stop innovating.

“Everyday we make new children—let’s also make new children’s books.”

—From Barnett’s Proclamation

Barnett writes and lives in Oakland, California. He is currently completing The Brixton Brothers, a middle grade series that lampoons The Hardy Boys.

This interview was conducted over email in October 2012.

Interview

Julie Judkins: You’re a vocal advocate for picture books. What specifically about picture books appeals or speaks to you? What does a picture book offer that other types of books do not (besides pictures, of course)? In your “Picture Book Manifesto” you state that picture books are “a form, not a genre.” Can you explain?

Mac Barnett: In picture books, the tension between the words and images generates tremendous narrative energy. Illustrations can amplify the text, or contradict it, or show you a story or moment the text never even acknowledges. It’s a uniquely flexible, uniquely powerful storytelling form, and a relatively young one, too. There are so many frontiers, so many new kinds of pictures books that can be written. And that’s a part of what I’m getting at when I say that the picture book is a form and not a genre. When people think of picture books as a genre they’re lassoing the form with a fairly limited set of narrative conventions. But there are many genres of picture books—science fiction stories, ghost stories, experimental fiction, biography—that share little other than certain formal characteristics.

What was your intention in writing your proclamation and how did it originate? If the proclamation were able to change the way people view picture books, what would you hope that change would be?

There’s been a lot of hand-wringing lately about the future of the picture book. Two years ago, The New York Times published a front-page article declaring the picture book dead. I disagreed with that thesis. But a lot of the response from the children’s book community seemed to be variations on the idea that the picture book was an essential form, even a magical form—and I thought both extremes missed the point. Picture books aren’t magic. Good picture books are magic. A perspective was missing from the conversation—things I’d discussed with friends and colleagues, ideas about what was right and wrong with our form. And so I tried to collect some of those ideas into a document. I hope that the proclamation fuels smart discussion about picture books and inspires people who have a stake in the form.

Despite your frequent collaborator author/illustrator Adam Rex (facetiously) saying he’s “read longer t-shirts,” the truth is that good picture books are deceptively difficult to write. How do you know that a picture book manuscript is working?

If I finish a picture book manuscript and it feels whole and complete and fully satisfying, I’ve failed. A good picture book does not work without illustrations. So a sense of the story’s visual potential is probably the number-one thing that makes a manuscript alive to me.

And while writing for kids requires sensitivity to the limits of your audience’s experience and lexicon, good writers are also often hobbled by adults’ ideas of “kid-friendly” material. I think it’s easy to idealize childhood and end up publishing stories that ignore the tough and complex emotional lives of children.

I’m curious whether your affiliation with 826LA has influenced your writing? Has working with young writers changed your perspective on the practice of writing or altered how you approach your own writing?

I think working closely with kids helps you see that children aren’t monolithic—that there’s no secret set of “things kids like.”

You’ve mentioned discovering an interest in writing for children while working at a children’s camp, where, in the absence of a good library, you began telling tall tales to entertain the campers. Your work in general is perfect for being read aloud or performed. Is this intentional? Does performance play a role in your writing process?

I’m glad to hear it—picture books are very often a performed art, and I try to take good care of the adults who read my books to children. There’s nothing worse than standing in front of a bunch of five-year-olds and stumbling over a line that doesn’t scan, or getting mired in a boring passage, or telling a bunch of jokes that don’t work. It’s not the writer who ends up looking bad—it’s the poor adult who’s holding the book.

Links & Resources

- Read “A Picture Book Manifesto.”

- You can also read Katherine Carlson’s recent FWR interview with Adam Rex, entitled: “Books Could Save Your Life.”

- Here is Julie Bosman’s 2010 New York Times article “Picture Books No Longer a Staple for Children,” which Barnett cites.

- The Barnett canon at Powell’s Books.