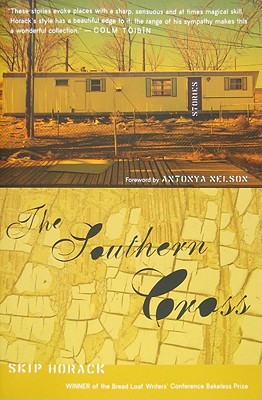

We share a mutual affection for Denis Johnson. Like his stories in Jesus’ Son, your stories include unusual, arresting images, often layered with religious or spiritual meaning. In “The Journeyman” for example, a Bible page gets pinned against the narrator’s leg, right after a young neighborhood girl tells him she used the Bible to kill a snake under his house. At end of the story, he says, “It was nice having her around, his steady lookout for pestilence and plague—a friend to help him recognize the angels among us and signs from God.” Likewise, “The Rapture” ends with these great lines: “I wonder whether it’s finally happened. I wonder if he’s gone and disappeared on me. Is it possible that the Tribulation has just now begun?” Is that a major theme in your book, this idea that some higher spiritual force, emerging from seemingly normal and mundane objects or images, is present all around us?

Yes. Now, I certainly can’t speak for Denis Johnson, but I try my level best not to think too much about theme going into any draft, preferring instead to proceed with the faith that themes will arise from the interplay of plot, setting, character, conflict, tone, etc. in my work. To me, seeing themes emerge is when fiction writing feels most like a process of self-discovery, and by not being overly concerned with theme in the beginning I can’t cheat and pretend to believe or value something that in fact I don’t. I really, really like what you have to say about my story, but that certainly wasn’t a “message” I imposed on the story intellectually and intentionally. Put simply, I prefer to have the story create the themes rather than vice versa.

That said, I do indeed seem to come back to religion a lot in my work, but I suspect that primarily has to do with the fact that, for me, religion often provides such great grist for the writing mill. As writers, we all draw from our own personal inventory of experiences and knowledge as we push forward on the page, and growing up in a part of the country where religion is so front and center apparently had a big influence on me. That actually wasn’t something I realized until I’d been writing for a while.

I also admire the nuance and complexity of your female characters. For example, Karen from “The High Place I Go.”

I also admire the nuance and complexity of your female characters. For example, Karen from “The High Place I Go.”

You’re paying me a very kind compliment, and I hate that I’m going to sound like a wiseass here, but I can’t help but be reminded of the Rebecca West quote: “Feminism is the radical notion that women are people.” As fiction writers, pretty much by definition, we have to write from the perspective of folks who are not us. Gender, race, age. On and on and on. Trying to see the world as others might seems like an act of respect to me—so long as it isn’t done cynically or sloppily.

In creating any character, I typically start from some place or aspect of connection, then explore and develop whatever differences as I roll forward (and there are differences, of course). Sometimes I do a good initial job of that, and sometimes I fail miserably—but thankfully writing doesn’t stop with the first draft.

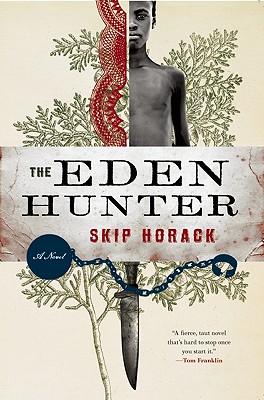

Your novel The Eden Hunter is quite distinct from the stories in your collection. Set in north Florida in the early eighteenth century, it’s told from the perspective of Kau, a slave who escapes from his captor, an innkeeper, and struggles to survive alone in the wilderness. I’m curious how this book and this character emerged. What kind of research did you do for this book, and how did you negotiate that line between historical accuracy and a fictional narrative? Did you ever feel bound by the historical research you’d done?

I used to live in Florida, and during my time there I stumbled upon the story of this fort that the British had built along the Apalachicola River during the War of 1812. Florida technically belonged to the Spanish back then, but it was also more or less a wilderness. This fort was not very far from the American border, and its purpose was to recruit runaway American slaves to enlist with the British in their war against the United States. The British were actually quite successful in convincing a large number of runaway slaves to join up with them, but before the fort ever saw battle the treaty was signed that ended the War of 1812. A few months later, the white British officers sailed back to England and left the fort in charge of these recruits.

So, for about a year and a half, you had this frontier fort—just across the border from Georgia—that was completely controlled by runaway slaves. This came to be a real thorn in the side for certain American slave owners because, even though the war was now over, many of the slaves in the Southern states and territories knew of the fort’s continued existence, and so quite a few of them continued to run and seek refuge there. The plantation owners complained to the government, until finally the American military agreed that something needed to be done.

For whatever reason the story of this fort is not widely known, and so I started doing what historical research I could—at first because the subject simply captured my imagination, but then also because, as time passed, I started to think that there might be a novel in this that I’d like to tackle.

The question then became how to tell the tale, and somewhere along the line I decided that I wanted to present the story of this fort from the perspective of an African pygmy who had been sold into slavery. Why I made that decision is hard for me to pin down, but I suspect it had a lot to do with the fact that man’s relationship with nature, as well explorations of displacement, have always been thematically interesting to me. Accordingly, what initially drew me to having an African pygmy as a protagonist was not some desire to be provocative or challenge myself, but rather the appreciation that perhaps no group of people has lived in greater harmony with nature than these indigenous pygmy tribes of Central Africa. And I became excited by the possibilities for my writing that might come from taking a person, and then, through tragic circumstances, dropping him in the middle of a landscape that I myself know very well and love—which is the pinewoods, swamps, and river bottoms of the South.

The question then became how to tell the tale, and somewhere along the line I decided that I wanted to present the story of this fort from the perspective of an African pygmy who had been sold into slavery. Why I made that decision is hard for me to pin down, but I suspect it had a lot to do with the fact that man’s relationship with nature, as well explorations of displacement, have always been thematically interesting to me. Accordingly, what initially drew me to having an African pygmy as a protagonist was not some desire to be provocative or challenge myself, but rather the appreciation that perhaps no group of people has lived in greater harmony with nature than these indigenous pygmy tribes of Central Africa. And I became excited by the possibilities for my writing that might come from taking a person, and then, through tragic circumstances, dropping him in the middle of a landscape that I myself know very well and love—which is the pinewoods, swamps, and river bottoms of the South.

As a writer, I am very often fascinated by characters who have suffered in some way, whether through displacement or encroachment or some other more specific and personal trauma. Now, Kau is obviously a fictional construction, and trying to get him “right” on the page, and treating him with the respect he deserves, called for an entirely different sort of research. He was in large part inspired by a Congolese pygmy named Ota Benga who (albeit a hundred years after the events in my novel) came to find himself living in America, and learning everything I could about that gentleman’s life, and pygmy tribes in general, was very helpful and instructive (and, in Ota Benga’s case, heartbreaking), as was a trip I made to the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo to spend some time in the Ituri Forest and with certain pygmy tribes that Kau’s fictional tribe was patterned after.

Finally, to answer your last question, yes, I did feel bound by my research, both historical and anthropological, but I also found that the research I conducted did more to inform and guide my writing than to handcuff it. In essence, there are two threads to the novel: my attempt to accurately reflect actual historical events and people, and the fictional journey of a fictional protagonist who finds himself encountering those historical events and people.

Right now I’m reading Blood Meridian for a graduate literature seminar. In that book, McCarthy’s descriptions of violence are detached, episodic, and devoid of ethical judgment or political commentary. In your novel, you seem to refrain from moralizing or “judging” the violence in terms of right/wrong, good/bad. Was that conscious on your part?

I’d like to think—or hope, rather—that my attempts to imagine and present slavery and violence in all of its horror, without any overt moralizing or commentary on my end, allows that horror to speak for itself more clearly and affectingly than any editorializing from me could.

The importance you place on landscape and the prevalence of religious themes reminds of some of my favorite Southern writers, including Flannery O’Connor, Tom Franklin, Larry Brown, William Gay, Ron Rash, and Brad Watson. Would you call yourself a Southern writer, or a writer who happens to be Southern?

I’m a huge fan of all the people you mention, but I’m not sure any two writers are ever walking the same path. I just think of myself as a writer, first and foremost (and I suspect they do/did as well). Still, I’m a guy from Louisiana who often writes about the South—so I don’t have any qualms with being referred to as a Southern writer, at least in a geographic sense. Basically, I’ve decided that if people are often asking you if you consider yourself a Southern writer, then you probably are one. And that’s fine—so long as I’m still allowed to write about whatever I want to write about!

Your next novel is scheduled for publication next winter (late 2014, early 2015, Ecco/Harper Collins). Do you mind if I ask what it’s about?

I’m neck deep in revisions right now, but you’ll excuse the change in voice, here’s the synopsis I used when I placed the manuscript:

The Other Joseph is narrated by thirty-year-old Louisiana native, convicted felon, and offshore oilrig worker Roy Joseph. Haunted by the disappearance of his brother in the first Gulf War, the tragic death of his parents, and the sin from his past that has branded him, Roy has shut himself off from the world, managing to live a life of quiet seclusion until the day he is contacted by a teenage girl claiming to be his lost brother’s biological daughter. After years of self-imposed exile, Roy finds himself in San Francisco, beset by mysteries both known and unknown as he struggles to form some bond with this girl, as well as to alter the course of his unhappy and isolated life.

Are you still writing any short fiction? Do you feel more comfortable writing stories or novels?

I’m currently working on a series of stories, and I’d love to perhaps see those in a collection one day. As for whether I feel more comfortable writing stories or novels—no, I definitely can’t say that one feels like it comes easier to me than the other. Though I’ll definitely admit that it is less maddening to carry a story in your head than a novel in progress!