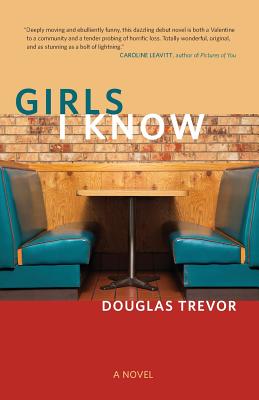

Girls I Know, Douglas Trevor’s debut novel, which was released this spring by Sixoneseven Books, is set in Boston and tells the story of a twenty-nine year old graduate-school-dropout Walt Steadman, who, after witnessing a tragic act of violence, searches to make sense of the tragedy and life in general with the help of two girls: Ginger Newton, a Harvard student, and eleven-year-old Mercedes Bittles, whom he begins to tutor. A coming-of-age novel, a novel about place, and a stirring social novel, Girls I Know is dark, deeply moving, and funny—a complex and nuanced book that defies categorization.

Girls I Know, Douglas Trevor’s debut novel, which was released this spring by Sixoneseven Books, is set in Boston and tells the story of a twenty-nine year old graduate-school-dropout Walt Steadman, who, after witnessing a tragic act of violence, searches to make sense of the tragedy and life in general with the help of two girls: Ginger Newton, a Harvard student, and eleven-year-old Mercedes Bittles, whom he begins to tutor. A coming-of-age novel, a novel about place, and a stirring social novel, Girls I Know is dark, deeply moving, and funny—a complex and nuanced book that defies categorization.

Trevor is also the author of the short story collection The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space (University of Iowa Press, 2005), which won the 2005 Iowa Short Fiction Award and was a finalist for the 2006 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for First Fiction. His short fiction has appeared in the Paris Review, Glimmer Train, Epoch, Black Warrior Review, the New England Review, and many other literary magazines. He lives in Ann Arbor, where he is an Associate Professor of Renaissance Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Michigan.

In his first scholarly book, The Poetics of Melancholy in Early Modern England (2004), Trevor argues that that writing can be both the cause of and cure for melancholy, and that certain writers such as John Donne and John Milton claimed having depression to enhance their artistic and intellectual street cred. Earlier this spring, while he was in Michigan and I was in Greece, Doug and I had an email conversation over the course of several days about issues of grief, sadness, writing, and more.

Interview:

Natalie Bakopoulos: Let’s start with the basics. How did you come to writing?

Doug Trevor: I began to write stories at a young age—six, seven. I think it was partly a way of avoiding my family, partly out of interest in reading and books. I really loved books as a kid. Reading was something that mattered to me, but in a way the material book mattered more. I just loved the way books smelled and felt in my hands. I had asthma—the kind of thing you can treat with a pill today and be on your way. But the medicine wasn’t nearly as effective back then so I spent a lot of days at home in bed. The rule in our house was, no TV if you were sick, unless you were in bed for three days, at which point the rules would bend. So the objective was to make it to the third day. The first day in bed, I would tend to read a lot. Then the second day I’d work on my stories. And the third day I’d watch reruns of “I Love Lucy” and “The Dick Van Dyke Show.”

Yet somehow you didn’t become a sitcom writer…Instead, you’re both a scholar and a fiction writer. How do these two pursuits influence one another?

They are complementary insofar as I procrastinate on one front by working on the other. So if I have an article due on King Lear, I might work on a short story as a way of avoiding the article. And if I’m supposed to finish up a story, I might instead read a book about King Lear. The best days are those during which I write fiction in the morning, take a break, and then get some academic work done in the afternoon. But the influence of the two on one another has been more unconscious for me than conscious. I’m working on a couple of stories now in which professor types figure prominently, but I’ve never tended to write, or read, fiction about academics, or novels set on college campuses. There are intellectual topics like medieval philosophy that I do find really interesting but that I’m not at all an expert on, and those I tend to engage with in my fiction. And I think, because my efforts at balancing two different careers have kept me at the keyboard quite a bit, I’ve been less inclined to feel blocked as a writer. I just try to chip away on both fronts every day.

Girls I Know is your second work of fiction. Everyone seems to have an opinion on writers’ second books: that they are the hardest to write, that it’s hard to live up to the first, etc. (I myself am terrified of it). What are your feelings about this? How did the actual experiences of writing differ?

It was a very hard book to write. To begin, it’s my first crack at a novel. I think I had a short story writer’s view of novel writing, which is that it couldn’t possibly be as hard to produce 300 pages that ostensibly starts and stops just once, as opposed to a collection of nine stories or whatever my first collection was comprised of, that started and stopped, let’s say, nine times. But in fact I found writing a novel to be incredibly difficult and slow going. When you are writing short stories, you are active and engaged with others in a much more immediate way: sending stories out, revising stories for publication, etc. But once I dug into Girls I Know, I felt as if I more or less disappeared from the earth’s surface. As a writer, I struggled some with that feeling of isolation. And I had so internalized the cadence and clock that dictates short fiction that once I let that go, I had a tough time figuring out how to pace a longer narrative. It really wasn’t until the third draft of the novel that I felt like I had a sense of how to manage the narrative arc. Then the project became incredibly fun and really all consuming. And then, somewhat sadly, it ended, and now I have to start the whole process again with another book project.

It was a very hard book to write. To begin, it’s my first crack at a novel. I think I had a short story writer’s view of novel writing, which is that it couldn’t possibly be as hard to produce 300 pages that ostensibly starts and stops just once, as opposed to a collection of nine stories or whatever my first collection was comprised of, that started and stopped, let’s say, nine times. But in fact I found writing a novel to be incredibly difficult and slow going. When you are writing short stories, you are active and engaged with others in a much more immediate way: sending stories out, revising stories for publication, etc. But once I dug into Girls I Know, I felt as if I more or less disappeared from the earth’s surface. As a writer, I struggled some with that feeling of isolation. And I had so internalized the cadence and clock that dictates short fiction that once I let that go, I had a tough time figuring out how to pace a longer narrative. It really wasn’t until the third draft of the novel that I felt like I had a sense of how to manage the narrative arc. Then the project became incredibly fun and really all consuming. And then, somewhat sadly, it ended, and now I have to start the whole process again with another book project.

I’m interested in what you said about isolation, and also about having had asthma as a child and all the quiet time that accompanied it. Quietness plays a huge role in Girls I Know—what isn’t said, for instance, or who has a voice, particularly in relation to race and class but also within relationships, between people. Can you talk a bit about this? In general, but also in relation to Ginger and Mercedes—both such complex characters, by the way.

You are so right to notice the huge role that quietness plays in the novel. Mercedes, the eleven-year-old whose parents are slain quite early in the book, does not speak until page 271. Ginger is a talker, but her book project—itself entitled Girls I Know—is organized around the idea that she will get other women to talk so that their voices will more or less drown out hers. I really admire Mercedes’s determination not to speak just to put people at ease—her refusal to talk when she doesn’t feel like talking. Ginger’s silence is much more rehearsed and problematic. She is a very strategic kind of person—very writerly in her own way—so I identify with her at the same time that I don’t fully endorse her mode of being.

And there is absolutely a class and race dimension in play here as well. Ginger is used to people listening to her, and she solicits and directs the speech of other women, hardly any of whom are as entitled as she is. Mercedes is an observer. Even before her parents die, she tends to watch people. I think when she is asked to speak in the predominantly white school she transfers to after her parents die, Mercedes recognizes those invitations to speak as inauthentic, as condescending—intended to put the people who ask her to speak at ease, not her—so she rejects them.

Do you know that Woody Allen movie Sweet and Lowdown, about the jazz guitarist played by Sean Penn?

Yes.

Sean Penn’s character, Emmet Ray, falls in love with a mute woman played by Samantha Morton. Morton’s character—I think her name in the film is Hattie—never speaks in the film. The role just blew me away because the character came across as so expressive and appealing. I filed the observation away. Then when I discovered, somewhat unexpectedly, that Mercedes was going to figure prominently in the novel, I thought it made sense for her to be introverted in the wake of he parents’ deaths, and initially I pushed this introvertedness to the point of muteness because I was nervous about getting her voice right. Fiction writing is the opposite of film in this regard, though, because once a character stops talking in prose, her narrative voice can really expand, rather than contract. In one sense, then, no one in the book talks as much as Mercedes does. We get her internalized stream of narration throughout much of the second half of the book, which I really enjoyed writing. Her voice ended up being the most appealing one for me, I think because words really matter to her. I also think I envy someone who just refuses to speak. I had a roommate my junior year in college who hardly every spoke. He just thought talking was overrated. I think he was right.

Well, please don’t stop talking yet! I have more questions. This is a big social novel, and it’s also a character-driven coming-of-age novel. Often we talk about novels being one or the other, which I find reductive. I love Saul Bellow’s idea that positions should not guide a work of art but emerge from one, though of course as writers we write from a certain angle. In Girls I Know, issues of privilege and race and class are front and center. Are these ideas you knew you wanted to explore? Or did they emerge from the process and narrative?

Isn’t Saul Bellow the best? I feel like he is the Shakespeare of the American novel. I did very much want to juxtapose class and race issues in such a way as to suggest that they cut across one another and inform one another in a more complicated manner than I sometimes think we allow them to in contemporary American discourse. So, for example, I wanted Mercedes and Walt to share a class background but not a racial background. And I wanted Walt and Ginger to share a racial background but not a class background. Walt is the hinge. Ginger and Mercedes share neither a racial nor a class background, and in fact they never meet in the novel, in part as a result. So I imagined that the book would be about privilege and race and class issues, but once I began to develop the characters and they began to do things, some of the evident “themes” of the book (to use that dreaded word) became more complicated than I had imagined, which I realized—I think even at the time—was a blessing, since otherwise the book would have seemed very axiomatic and stiff. Walt and Mercedes, for example, end up sharing a class background in a way, but in another way they don’t, because of race. At the very end of the book, Walt says to Ginger, “You were right and wrong about America: about class, about race. I was right and wrong as well.” I feel like I was right and wrong, too. The categories can’t be separated entirely and I think Girls I Know ended up being in part about that, which I hadn’t anticipated.

The idea of home figures prominently throughout the novel: where it is, where we make it, and how we define it. Many of these characters have been displaced, and many find themselves in, or claim, places that aren’t their own. This is clear from the beginning and takes on a new, illuminating glow at the end, which just about rises off the page. How do ideas of home operate here, in your opinion?

You’re right that all the central characters in Girls I Know are away from home through most of the book. I hadn’t really realized until now the degree to which this is simply true. Mercedes is in her grandmother’s home after her parents die, but she won’t be able to stay there for long. Like Walt, she is looking for a home. Ginger is the kind of person who has the resources and the confidence to make any place a home, or not to care about having a home insofar as that word means a safe place where you are surrounded by people who love and care for you. Home is a charged concept for me. My first book, The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space, circles around the unexpected death of my sister, and the last story in the collection ends with the two of us as children, in our childhood home, thinking about where we will be in the future. It sounds obvious, but when someone you care about dies, whatever space you inhabited with them changes forever. It becomes just saturated with melancholy and loss. Mercedes misses her family’s apartment painfully throughout the course of the book, but she doesn’t want to see the apartment—not without her parents in it. Much of Walt’s journey in the novel is toward trying to understand what it means to adopt a city as your home, only to have it then traumatize you. Like most of what I write about, then, my sister’s death is lurking there, in the homes that do and do not appear in Girls I Know. Also, I’ve moved around a lot in my life so I feel really aware of the degree to which my “home”—say, in Ann Arbor—will never be my “hometown,” which is Denver.

You’re right that all the central characters in Girls I Know are away from home through most of the book. I hadn’t really realized until now the degree to which this is simply true. Mercedes is in her grandmother’s home after her parents die, but she won’t be able to stay there for long. Like Walt, she is looking for a home. Ginger is the kind of person who has the resources and the confidence to make any place a home, or not to care about having a home insofar as that word means a safe place where you are surrounded by people who love and care for you. Home is a charged concept for me. My first book, The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space, circles around the unexpected death of my sister, and the last story in the collection ends with the two of us as children, in our childhood home, thinking about where we will be in the future. It sounds obvious, but when someone you care about dies, whatever space you inhabited with them changes forever. It becomes just saturated with melancholy and loss. Mercedes misses her family’s apartment painfully throughout the course of the book, but she doesn’t want to see the apartment—not without her parents in it. Much of Walt’s journey in the novel is toward trying to understand what it means to adopt a city as your home, only to have it then traumatize you. Like most of what I write about, then, my sister’s death is lurking there, in the homes that do and do not appear in Girls I Know. Also, I’ve moved around a lot in my life so I feel really aware of the degree to which my “home”—say, in Ann Arbor—will never be my “hometown,” which is Denver.

Jesmyn Ward [National Book Award Winner for her novel Salvage the Bones] says in her beautiful essay “We Do Not Swim In Our Cemeteries,” about the unexpected, tragic death of her brother and of Hurricane Katrina, which devastated her own hometown on the coast of Mississippi:

Even after that which you love dies, the love you have for it does not die. Grief is learning how to live with that love. My small town dies and becomes something else.

I think this is a particularly evocative way to describe grief, and it seems to apply very well to Girls I Know, and also regarding your earlier comment that “when someone you care about dies, whatever space you inhabited with them changes forever.” Do you see writing as a way to exercise, and exorcise, grief? Fear? Darkness? Or as a way to explore its presence, perhaps?

I do think that’s an apt way to describe Girls I Know: as an exercise in living with grief and trying to marshal or use grief in order to turn toward, rather than away from, the world. I don’t think writing exorcises loss—at least in my experience— so much as it attests to its shaping power. I suppose different mysteries compel different writers, but for me the experience of surviving loss is something I’ve thought a lot about. This was true even before my sister died. My father lost both his parents at a really young age: his mother to breast cancer at twelve, his father to stomach cancer at thirteen. So I grew up with this story of loss very much in our family. I wanted really badly to know the details of how my father got by with his parents gone. I knew he had an aunt who moved into his family home to raise him, but I never managed to get very many details out of him about that arrangement. The stories I wrote as a kid were, I think in hindsight, oddly dark partly because of this mystery of my father’s childhood.

But in broader terms, the way landscapes—human and natural—rebound from death, the way the machinery of life just continues on, regardless . . . I find that dimension of reality to be quite an extraordinary thing. At the end of Girls I Know, Walt and Mercedes walk by the former Early Bird Café and the restaurant space has already—in just a few short months—been remodeled and redone: refitted for its next occupants. That to me is very indicative of our contemporary moment—the way we have almost come to expect our lived experiences to be replaced in due course. That strikes me as a very American kind of reality. As opposed to permitting a crumbling Parthenon to remain in our midst for centuries, for example.

Which I’m looking at now, by the way, as we talk. So. Speaking of grief. Finishing a novel, I’ve found, though nothing like experiencing a real loss, is a sort of loss. I was devastated and relieved at the same time. And then excited and nervous to start the next thing. So back to what we started, with a twist, or a bit more: do you have something in the works now?

I do have a sense of my next novel, and I have a little bit of it done. Bob Stewart at New Letters is publishing chapter three in the fall as a stand-alone story entitled “Slugger and the Fat Man.” The novel is set in Denver and it is a spiraling and capacious thing: imagined mostly at this stage as interlinked stories. I want to write about a young man who discovers that the contours of his family are other than he imagined them to be growing up, and I want this discovery to parallel a retelling of the history of the West that is less clichéd and more in touch with the profound ethnic, racial, and political tensions that were a part of the westward migration. The plan is to skip around and pick up different characters at different junctures in the history of Colorado, although I will stick mostly to the contemporary moment.

And the contemporary moment is?

At the center of the story is a messed up dad (the subject of the piece coming out); a politically outspoken, ancient bookstore owner; a young woman of Japanese descent who is dating the central character; and the central character, Luke, who discovers as the narrative unfolds that he is connected to everyone around him, in one way or another. So there are lots of characters, lots of different sub-stories, lots of stuff about Denver. The plan is to do most of the research this summer and to try to write the book in pieces, at least initially. I’m hoping in part that writing the book as interlinked stories will enable me to stay connected more to the world of journals and magazines. One of the things I missed most during the final stages of Girls I Know was sending work out and having interactions with editors and readers. So I’m hoping this approach will mitigate some of the loneliness that comes with trying to write novels.

I hope so, too, Doug. Thanks so much for talking with me.

Thank you, Natalie.

Further Links and Resources:

- For more on Douglas Trevor and his work, please visit his author website.

- Read an excerpt from Girls I Know in Issue Forty-Six of The Collagist.

- You can also check out Doug’s “Stories We Love” post on Raymond Carver’s “A Small Good Thing” for this year’s celebration of Short Story Month.

- Read an interview with Natalie Bakopoulos, whose debut novel, The Green Shore, was just released in paperback.