About Valerie Laken

Born and raised the youngest of four children in Rockford, Illinois, Valerie Laken graduated from the University of Iowa, where she majored in English and Russian. In the early 1990s she lived in Russia, Poland, and the Czech Republic, working as a translator and teacher, and trying to come up with stories to write. Eventually she received an MA in Slavic Literature and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Michigan. Her short stories have been published in Ploughshares, Alaska Quarterly Review, Antioch Review, and elsewhere, and they have received a Pushcart Prize, a Missouri Review Editors’ Prize, and an honorable mention in Best American Short Stories . Valerie is currently an Assistant Professor in the creative writing program at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee.

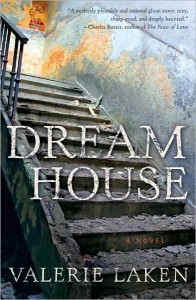

Her first novel, Dream House (HarperCollins, Feb. 2009), tells the story of a young couple whose lives are upended when they discover that the historic home they’ve just bought was once the site of a murder. When the man who committed the crime gets released from prison and begins lurking around the house, the book gradually reveals the complexities surrounding this domestic homicide and charts the shock waves that spread out from that one terrible act to shape the lives of many disparate characters.

Her first novel, Dream House (HarperCollins, Feb. 2009), tells the story of a young couple whose lives are upended when they discover that the historic home they’ve just bought was once the site of a murder. When the man who committed the crime gets released from prison and begins lurking around the house, the book gradually reveals the complexities surrounding this domestic homicide and charts the shock waves that spread out from that one terrible act to shape the lives of many disparate characters.

Foundations: A Conversation with Valerie Laken

PEGGY ADLER: Soon after you moved into your house, you learned that there had been a murder there years earlier, and this became the catalyst for your novel.

VALERIE LAKEN: Right. I made the unenviable, idiotic move of talking my husband into buying a truly atrocious run-down home against his better judgment, and then two weeks after we moved in, a neighbor stopped by to introduce himself and told us—with a certain depraved glee, I felt—that a murder had once occurred under our roof. The worst part was that he didn’t know the details of how or when the crime had occurred, so we were left to imagine worst-case scenarios for weeks. Finally, another neighbor stopped by and told us a more complete account of the crime, and that story struck me as so powerful and, I don’t know, noble—if you can use that word to describe a shooting—that it transformed my impression of the house. It was a domestic homicide, with all the emotional complexity that such crimes must often involve, and it ended with the killer taking the gun down to the corner store, setting it on the counter, and saying, “Call the police, please. I just shot my mother’s boyfriend.”

When I heard that story I stopped feeling afraid and ashamed of our house and just became intrigued by the mystery of what it would take to make someone with that kind of honor and manners, even, commit a homicide under his own roof.

Did you have a novel brewing in you before you learned the history of the house?

No way. I was a perfectly happy short story writer with no ambitions beyond putting together 15 or 20 pages that my writer friends liked, and trying to get them placed with my favorite semi-obscure journal. I’m a short story fanatic; it’s baffling to me that the short story is not the most popular art form on the planet. To me they hold everything. I read them much more often than novels. I find novels daunting, not just to write but even to read. I’m an extremely slow reader, and I think I have trouble holding together all that a novel contains once it’s spread over the long time span required for me to read it.

Yeah, I personally find the craft of writing a short story to be more challenging than the craft of writing a novel. But if you didn’t have ambitions to write a novel for its own sake, what made you know that Dream House had to be a novel? Did you know when you started writing it, or did it begin as a story?

I knew from the beginning that this idea would involve braiding together at least three separate character trajectories and plot lines, so I think I knew that this would be a novel from the beginning. In my ignorance, I was drawn to the challenge of a larger project. But soon after I began it, I became intimidated to the point of paralysis by the prospect of writing a novel. I mean, anyone who has gone through even one writing workshop has received a whole truckload of advice about how to pursue the writing of a short story. When it comes to writing novels, though, we are very much on our own. I had already finished my MFA experience, and although I had lots of excellent, very supportive writing friends and mentors, their advice about writing a novel more or less boiled down to: Shrug. Nobody ever knows how to do it. You just do it.

I agree with your comment that writing a good short story requires a very exacting degree of skill, whereas novels can have a few flaws and still be widely loved. I don’t think people expect perfection from a novel as they do from a short story. I can wince and squirm over a single line when I read a story, but in a novel, when I encounter a bum line, even a bum paragraph or chapter, I often just shrug and keep reading onward.

On the other hand, writing a novel requires so much more stamina and faith than a story. It’s a little like those people who get in their sailboats and sail to a far-off island, just for the adventure of it. I always think they’re insane, because the idea terrifies me: what if you get lost out there all on your own, and no one knows how to find you? Most of writing a novel feels like that kind of middle-of-nowhere, you’re-on-your-own sort of journey. And there are so many days when you wake up in the middle of the ocean with no wind in sight and think, “Why the hell did I sign on for this?”

Did you ever find the need to get away from the book and write stories again?

In the early years of writing the novel I did sometimes take breaks to write stories, but after a while I forced myself to stop doing that. It was often a nice break, and sometimes it helped rebuild my rapidly waning confidence in my ability to write or complete anything of any value. But ultimately I realized that if I was ever going to finish this novel, I would have to give up just about every other distraction and pour everything I could muster into this one book. That sounds so ridiculously grandiose now, but really it felt that desperate, that life-or-death, at the time.

I’m getting way ahead of myself here, but can you imagine yourself writing another novel any time soon, or are you happy to be back to stories?

I’m a little afraid to say. I am hatching a plan for a novel, and I do want to write another novel before too long, but right now I am working on short stories, and that feels like a great relief. There are all sorts of anxieties that can creep into the process of writing a novel, especially anxieties dealing with the prospect of publication—of whether or how this crazy project you’ve worked on for years may get published, and how the world at large may react to it. With short stories, you never really expect the World at Large to care one way or the other. It’s a labor of love, and no one disputes that, and I think the purity of that endeavor is very liberating.

Okay, back to Dream House! You and your husband were rebuilding your house at the same time that you were working on this book. Can you speak to the relationship between working on a house and writing a novel?

There is something very reassuring about houses. Really the two things that define a house, any house, are that it is meant to endure and meant to protect an intimate group of people. That’s stating the obvious, I guess, but what I mean is that basing a novel around a house was a way of anchoring a project that terrified me to a stable and necessary object.

At the same time, lots of people live with the fear that their home won’t endure—that it’ll be taken away by the bank or blown to bits in a hurricane. The past few years have given us ample news reports to support those fears. And although homes may generally protect us from the elements, lots of people also receive their most painful wounds inside their homes. So I was interested in the ways that homes can be both nurturing and damaging.

Dramatically speaking, placing a home at the center of your book (as so many other, better authors have done) is also very useful, because a home can bind your characters together and force them to work through their conflicts. After all, narratives don’t just require conflict or tension—which we can have with any stranger on the highway, fleetingly. What a story requires is characters who are in conflict but can’t walk away from each other.

That’s nice. Charles Baxter used to say: “Crowd your characters.” We spend so much time alone when we write, but what we’re interested in is what happens when we’re stuck together.

Yes. One of the most memorable stories one of my students ever wrote was about 3 people on what was supposed to be a date, driving around recklessly in a rickety old Volkswagen bug. The story may have had flaws, but the instincts of that writer were perfect. You just know that no matter what kind of characters you throw into that circumstance, something interesting is going to boil up to the surface.

So you have all of these characters bound to one house—many from intense past experiences—and their stories intertwine in the present action of the story.

The characters in my book all have powerful but different relationships to this house, and they can’t quite walk away from it or, therefore, each other. There is a young couple: Kate, who believes buying this old house will help mend her failing marriage; and her husband, Stuart, who has a bad feeling about the house and knows that no house can fix what’s broken between them. Then there’s Walker Price, the man who committed a murder under their roof 18 years ago, but who was raised in the home and can’t bear the fact that his crime destroyed his family and cost them the home. Finally, there’s another character whose life was unexpectedly altered after the night he spent cleaning up after the crime scene in the house.

Your willingness to write from Walker and his family’s point of view strikes many, myself included, as brave.

Walker Price and his family are African-American, and he commits a crime that I have a lot of trouble imagining myself ever committing, and he has spent half his life in prison. So he’s different from me in significant ways, and I definitely found it frightening and challenging to try to write from his point of view. It felt like an audacious move, a big risk. At some point someone said to me, “Well, if you’re afraid of writing an African-American character, you could just make him white.” That took my breath away, and I realized very suddenly how important the question of race was to me in this book. Especially the question of how race functions in a town as progressive and supposedly post-racial as Ann Arbor, where the book is set.

You’re saying that Walker was African-American simply because the real person he’s based on was African-American, and that you never set out to write a novel about race?

Yes.

Did you ever worry that you didn’t have permission to write him?

I often worried that I didn’t have the right to write Walker’s character, and that worry sometimes paralyzed me. But there is probably also a part of me that feels that writing only comes alive and becomes worthwhile when we’re really risking something. I mean, anyone can write what’s easy to write. Our job is to try to write the things other people are afraid to say. I’m not sure I succeeded, but that philosophy was helpful.

Research is also helpful and necessary. I read a lot of prison memoirs, trying to hone a voice for this recently paroled character of mine, and what I ultimately discovered was that there is, of course, no single voice or speech pattern for parolees or African-Americans or any group you want to name. Every voice is unique. And Walker Price’s voice would be particularly unique, because he spent his first 14 years in inner city Detroit with a father who couldn’t abide street slang, then 4 years in affluent Ann Arbor, then 18 years in prison. There is no set voice for that, or for any of us. You create the voice along with every other part of the character.

For me a big key to figuring out Walker, and coming to love Walker more than any other character, was to discover that he had a lot in common with my main character, Kate: they both came from strict, ambitious fathers with high expectations for their families, and they were both fiercely attached to this house as an expression of their family’s status.

And the heart of your story seems to be when Kate tells Walker that she wants to hear his story. To me, that’s what your book is about: As Kate begins to understand her parents’ marriage, as Walker begins to understand that his mother loved D.B., etc. Yours is a story about what happens when we open our hearts and listen to each other.

Well, thank you. That’s very flattering to hear. I don’t know… My earliest concept for the novel was that the book was not so much a book about the house itself as about a series of characters passing along stories about the crime in the house. The story of the crime would be a burdensome thing to know, and each character, having heard it, would be reshaped by that knowledge in unpleasant, unpredictable ways, and would therefore have to look for ways to off-load that story to someone else. That was my original plan. Over time the novel evolved beyond that original idea, but there are still remnants of it—in the prologue, for example, or in that passage you mentioned—when the act of storytelling becomes transformative and dramatic.

You also do a beautiful job writing from multiple points of view in this book, which is part of how you earn the story’s complexity. Did you ever change point of view while writing? And how did you arrive at the choice to write in the third person vs. the first?

I think there were a few very early, sketchy, brief drafts that had Kate narrating in first person—which is really my preferred narrative mode—but I realized early on that this particular story was going to require multiple points of view. And I heard Elizabeth McCracken say at a reading once that a writer should never attempt multiple first-person points of view in a novel unless he or she was named William Faulkner. She was joking, sort of, but I took it to heart and quickly switched to third person.

In terms of deciding which characters’ perspective to enter, that was definitely a strategy that evolved over time, and was a subject of some debate among readers of the drafts. There used to be chapters, for instance, in the perspective of Walker’s mother, but I ultimately found them unnecessary and cut them, even though I loved them. My favorite chapter is Chapter 25, which I think of as sort of the house’s point of view, and some readers felt I should have done more chapters in that perspective, but I liked the way that it stood out as unique in that pivotal moment of the book.

The problem with opening up to multiple points of view is deciding which points of view are truly essential. Some early readers felt Stuart’s point of view passages were not essential, and I entirely rewrote them more than once, trying to convince those readers, because for me it always seemed necessary to have his point of view riding alongside of his wife’s. It was important to me that this not just be “Kate’s story.” It was really important to me that this book be more expansive than just one woman’s perspective on her house. This probably had something to do with my sensation that a novel is kind of like a mural rather than a portrait. To me, the whole point of a novel is that, unlike most short stories, you get to portray an entire community coping with a variety of related problems. I thought, well, if I’m going to go to all the trouble of writing a novel, then I want to take advantage of all the liberties the genre affords.

Of course with multiple points of view you have so many threads, characters, and stories to keep track of. Did you figure out any of those plot points beforehand, or did you just work it out through the writing?

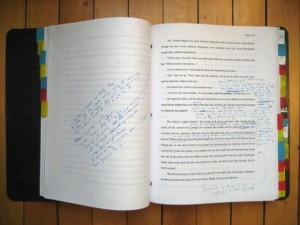

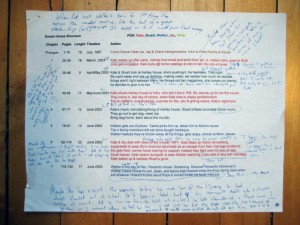

I charted out the plot lines of the book many times, in different colors and schemes, trying to keep track of what each character was up to and how their paths could cross again. I’m a fairly visual person, and there was something reassuring about charting out the book’s structure that enabled me to relax more in the writing of a given chapter and just watch what the characters might naturally and unexpectedly do next. And then, of course, they would often surprise me, and I’d have to go back and change my charted plan.

That’s really interesting. Did you do that charting after you had a relatively complete first draft, or did you start plotting from the get-go?

Somewhere in between. At first I just wrote and wrote, but I found the scope of the novel so daunting that it was paralyzing me. So I started charting things out, and that lifted the burden and clarified my vision of the project.

Since you did switch point of view, I wonder if you worked on the story chronologically in early drafts, or if you ever worked on one character for a while, then spliced it in the editing room?

Sometimes I cut chapters apart or spliced them together for the sake of structure, but I did not write one character’s entire trajectory and then move on to another’s. I wrote the chapters alternating between characters, more or less in the order they appear in the book. I would say, “OK, if I can just get through this chapter, then in the next one I get to go back to X’s POV, and that’ll be easier.” Or something like that.

Did switching point of view appeal to the short story writer in you?

Yeah, definitely. One of the great joys of short story writing is that you pour everything you have into 10 or 20 pages, knowing that when it’s over you get to put it all behind you and start over with a clean slate, a whole new set of characters and ideas. When I was writing this novel, I had a friend who was writing a novel that focused on one character, one point of view, chapter after chapter. I remember thinking, Man, don’t you get sick of that character? At the same time, sometimes I kicked myself: Man, why didn’t I just start off with one of those beautiful little quiet, first-person, coming-of-age, 180-page novels? That sounded like such a joy to me, though of course those novels contain their own scary challenges.

Were there any characters whom you didn’t expect to play such a large role—or didn’t expect to be in the story at all—who ended up stealing the show?

You’re thinking of Charles Baxter, aren’t you? He said that about his marvelous character Chloé in The Feast of Love—that she just hijacked his novel, to his and everyone’s delight.

I was thinking of Chloé!

For me, the characters of Jay and Stuart became very interesting, and I couldn’t let them go. I like to write from male perspectives. At first I thought those two might play lesser roles, but the more I wrote through their points of view, the more I wanted to spend time with them, regardless of how it might complicate the book’s structure.

I also wondered if Tasha’s character grew in Dream House. I love Tasha.

Yeah. Thanks. I really like her too. She did grow beyond the role I’d maybe originally imagined for her. But there’s a part of me that feels she could have played an even bigger role. I had trouble with that: at some point I realized I could have had a much more expansive novel, and I think I was afraid to attempt that. Sometimes I wish I’d had more courage in that regard.

Oh, your novel is plenty courageous—you have to go deep into these very personal lives, not just close to home, but at home. Speaking of which, I often find that it’s hard to write about a setting while I’m in it; I need distance. What it was like to write about your house while you were living in it?

It definitely felt oppressive sometimes to live in the house both in real time and in the imaginative space of my writing time. I am a bit of a homebody, and I get very absorbed by whatever home I’m living in, so yes, sometimes that experience was oppressive, overwhelming. Eventually we moved, and I actually finished the novel revisions in Milwaukee, where I live now. The writing picked up immediately once we moved. I think it’s always easier to write about a place once you have some distance from it. No matter how much complexity we want our writing to include, to be at all comprehensible, writing still probably has to be at least somewhat more simplified than our true, unfiltered experience. So getting physical distance from a place or event will usually make it easier to write about in fiction. The imagination needs a little room to breathe.

That’s really interesting; I never thought of the process of distancing as one of simplification, but you’re exactly right: Before you can imagine, you have to empty a space or setting, and yourself. Thanks for that.

De nada.

We started with the future, so let’s end with the past. What brought you to writing? How would you describe your relationship to reading as a child in Rockford, Illinois?

A childhood friend of mine just reminded me that in sixth grade I did a very impassioned presentation on Jim Morrison, who evidently struck me as a genius poet. My reading was, in other words, pretty eclectic and unguided. I was definitely shaped more by music lyrics than by books, and when I write I often hear the cadence of the next sentence before I know exactly what it will say. My parents are not really readers, and they did not keep books in the house, although one of my sisters was an avid reader who turned me on to things like Franny and Zooey and On the Road and The Stranger in my early teen years. I do remember going to the Rockford Public Library every Friday as a very little kid and curling up on benches and windowsills with stacks of books, though I think my mother brought us there only because it required us all to be quiet for a few hours.

So did you always feel like a writer?

Becoming a writer was my earliest dream, and I wrote constantly but clandestinely throughout my childhood and adolescence. But coming from a more or less working-class mentality, I always felt it was preposterous and arrogant for anyone to imagine that they could ever become a writer. (I don’t know where I thought writers came from. Dropped from the sky, I guess, or at least the east coast.) So I settled into slightly more practical, unassuming vocations, studying literature, language, translation, etc. I really love pushing words around on a page in solitude, so all of those fields hold a lot of appeal for me. I double majored in English and Russian as an undergrad at the University of Iowa, and then lived in Russia and Eastern Europe for a few years, working as a translator and a teacher, and all of that felt fine, almost close enough.

What drew you to that part of the world?

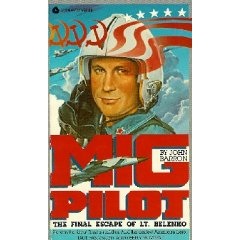

I don’t know. I think that growing up in the Cold War Reagan era really piqued my interest in Russia. There was a rumor in my town that we were on the top ten list of cities the Soviets would nuke first, supposedly because of certain essential machine parts that we made. Who knows if this was ever true, but I had a lot of nightmares about nuclear war and Soviet soldiers storming my house—ridiculous Red Dawn stuff. In high school I had an economics teacher who pitched us all sorts of anti-communist propaganda, including MIG Pilot. This was a fun read, sure, but a pretty one-sided account of the degeneration of the Evil Empire, and not much of an economics text. But I just didn’t buy this extreme, good v. evil presentation of it all. I wanted to find out more. So when I got to college I signed up for Russian classes (and sure enough: one of the first words they taught us was spy). Eventually this led me to Chekhov and Tolstoy, Gogol and Nabokov, and then I was hooked.

I don’t know. I think that growing up in the Cold War Reagan era really piqued my interest in Russia. There was a rumor in my town that we were on the top ten list of cities the Soviets would nuke first, supposedly because of certain essential machine parts that we made. Who knows if this was ever true, but I had a lot of nightmares about nuclear war and Soviet soldiers storming my house—ridiculous Red Dawn stuff. In high school I had an economics teacher who pitched us all sorts of anti-communist propaganda, including MIG Pilot. This was a fun read, sure, but a pretty one-sided account of the degeneration of the Evil Empire, and not much of an economics text. But I just didn’t buy this extreme, good v. evil presentation of it all. I wanted to find out more. So when I got to college I signed up for Russian classes (and sure enough: one of the first words they taught us was spy). Eventually this led me to Chekhov and Tolstoy, Gogol and Nabokov, and then I was hooked.

After college and a couple of years in Eastern Europe, I came back and entered a PhD program in Slavic Literature at the University of Michigan in 1995. By that point I was trying to write fiction on the side, but I had no idea what I was doing. One day I came across a little sign in a coffee shop advertising a writing workshop with Josh Henkin, a novelist I really admire, who had gotten his MFA at Michigan a few years before. The class was hard for me at first, but I ended up taking it several more times. He had a discount for repeat offenders, and after a while there was a whole group of us repeating—Nick Arvin, Don Lystra, Mary Jean Babic, Ami Walsh. Writers I really admire. I discovered how helpful it is to have that kind of community. Writing’s too hard to keep the faith all alone.

Then I took a writing workshop at Michigan with Nick Delbanco, and he sort of pulled me aside one day and said, “If someone could grant you a wish: either a PhD in Slavic Literature, or a published book of fiction, which would you choose?” I immediately said, “A book of fiction.” But I answered the way you would say, “A winning lottery ticket,” because that’s how obvious but out of reach the goal felt to me. And then he said, “So what are you doing in that PhD program?”

That was it: I applied to the UM MFA program. I tried to finish my dissertation at the same time, but my heart wasn’t in it, and Slavic Studies is too challenging a field for anyone — let alone me — to succeed at half-heartedly.

Did you ever question your decision to leave the PhD behind?

Never. I actually think it’s a lot harder to get a PhD and a tenure-track job in Slavic literature than it is to publish a book of fiction. It’s an incredibly demanding field, filled with geniuses, and I just wasn’t made of that stuff. I was starting to get the sense, anyway, that writing was my calling, and that whether or not I could succeed at it, it was the thing I wanted to devote my life to. Not just the writing itself, but the workshop environment as well. I like the communal aspect of it, especially the way that a good workshop engages students as complete humans, not just receivers of information. Best of all, we get to analyze literature not as an already accomplished text but as a live experiment in progress, with any number of possible outcomes and strategies for achieving those outcomes. That feels both practical and thrilling to me.

Further Resources

– Read the just-published review of Dream House in the New York Times; reviewer Marilyn Stasio calls Valerie Laken’s debut “the perfect haunted house story for these unnerving times.”

– Go here to read an excerpt from Dream House, or browse inside the novel on HarperCollins’ site.

– Learn more about Valerie at her website, see when she might be reading in a city near you, and keep up with Dream House news on her blog.

– Listen to another interview with the author, this one from Greg Berg’s WGTD Morning Show.