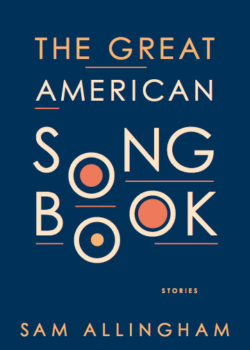

Sam Allingham’s short story collection, The Great American Songbook, makes a powerful and curious bid for attention with its title and cover design. The title of the book is also a title of the final story in the collection, but the cover hearkens to the celebrated Best American anthologies—and then one is left to wonder: is this indeed a collection of stories? Of songs? Or stories about songs? And is it a collection of great American songs we’re talking about here, or a songbook for the great American, if such a thing could be said to be proverbial?

The answer is all of the above, and that is only the beginning of what makes this collection deeply compelling and intriguing. Sam Allingham’s stories are embedded in American music culture and many of its musical traditions. Two of the stories are literary interpretations—or, “covers”— of songs by Modest Mouse and The Talking Heads. Allingham’s stories borrow from musical devices like modulation or variation on a theme as much as he works with literary devices like the turn of the screw. All of it works, and works masterfully.

Allingham studied at Oberlin College before he became a music teacher, and received his MFA in creative writing from Temple University in 2013. The Great American Songbook, his debut collection, was published by A Strange Object in mid-November.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: Let’s begin by setting the scene: we are conducting this interview via email. Where are you as you are responding to these questions? What time of day is it? How does publicity work for your book fit into your writing and teaching life these days?

Sam Allingham: I am currently sitting in the front room of my house in West Philly, around two o’clock, staring out the window at the street and considering a gigantic pile of leaves I should probably be raking. It’s about a week and a half since the book came out, and it’s been a crazy whirlwind, but I haven’t done much traveling to promote the book as of yet, which means I’ve been more or less able to maintain my work routine: getting up early, grading student papers, trying to find time for my own writing. This is a good thing, since I’m not the sort of person who likes to leave my neighborhood if I can help it! Still, reading my students’ work keeps me plenty busy, and the end of the semester is coming soon, sure as an approaching train.

When did you begin working on the stories in The Great American Songbook? How did the stories take shape as a collection over time?

The earliest of the stories was written when I was twenty-three–roughly nine years ago. Shocking to consider, especially when I think about how different I was in my early twenties than I am now! So, in a way, there are several different writers sequestered in the collection, and when it took time to figure out how these different people were going to get along I realized that the common thread was music. I wrote the majority of the stories when I was a music teacher, sometimes in breaks between lessons, and even the ones that came later are clearly obsessed with songs. That was actually the original title of the collection: Songs. There was just so much music in the stories, it seemed to make sense.

The earliest of the stories was written when I was twenty-three–roughly nine years ago. Shocking to consider, especially when I think about how different I was in my early twenties than I am now! So, in a way, there are several different writers sequestered in the collection, and when it took time to figure out how these different people were going to get along I realized that the common thread was music. I wrote the majority of the stories when I was a music teacher, sometimes in breaks between lessons, and even the ones that came later are clearly obsessed with songs. That was actually the original title of the collection: Songs. There was just so much music in the stories, it seemed to make sense.

From reading The Great American Songbook, I would assume that you not only have a sure knowledge of music theory but also experience as a performer. What is your musical background, and how do you see it fitting into your fiction?

As I said, I was a music teacher for about four years in my twenties, and I’ve always played in bands, more or less my whole life–but I wouldn’t consider myself a natural musician, necessarily. There are some people who can just pick up an instrument and sort of sing through it; I’ve played with some of them, even taught some of them, and there’s a real difference between a natural musician and a person who struggles their way into a kind of fluency. I’ve always been a little bit too cerebral, not fluid enough: a better teacher, maybe, than a musician. With music, you’re always working within time, at the mercy of the beat; with language you get a chance to step back, to revise, to work a sentence until it feels right. But you don’t get that immediacy, the way you do with music, especially live music. I’ve always been jealous of the directness of music: the way it seems to bypass rational thought and go straight to a deeper part of the brain. A lot of the stories in this collection–especially the ones like “Love Goes to a Building on Fire” and “Tiny Cities Made of Ashes,” which are direct “covers” of the songs that provided their names–were attempts to get at that directness through linguistic means, although I don’t think the attempts were ultimately successful!

How did you develop the comparative and dialogic structure for the first story in the collection, “Rogers and Hart”? It’s almost hypnotic in moments—and the structure also allows you to reveal details about each character and tell the story of their relationship with almost no action at all.

It’s a development from Donald Barthelme’s “Robert Kennedy Saved From Drowning,” a story I’ve always loved; I just added a second character. But the comparative format was fun, because it allowed me to keep adding little details about their partnership. I also cribbed a lot from Lydia Davis in this one, who likes short section headings that seem to organize the story, even when the headings themselves are ridiculous. Your point about action is an interesting one; I like to talk to my students about the ways you can imply action without actually describing it, which allows for a certain amount of compression. A shopping list implies a shopping trip. A bruise implies a fight. And, when you use a flat, sort of journalistic tone, you can shoehorn a great deal of action into a single sentence. For instance, Hart’s death is taken care of in a single clause.

Let’s talk about the use of the present tense in this collection, which contributes to the journalistic tone of “Rogers and Hart,” the unsettling dissonance of “Stockholm Syndrome,” and the shock and grief of “Husbandry.” How did you decide to write these stories in the present tense? How aware were you of the way it affected the tone of each story?

I use present tense because of its immediacy, and because it’s easy, once you establish the present frame, to move fluidly into the past without using pluperfect (the most dreaded tense). Present tense also has an appealing flatness, as if you’re describing the most mundane stuff, because it’s the tense we use when telling little stories or jokes. “So I walk into the room and I realize I’ve forgotten the salad.” “So a duck walks into a bar.” That makes it particularly effective when writing about horrible stuff, like the gruesome hostage situations in “Stockholm Syndrome” or the body transformations of “Husbandry.” It sort of lulls the reader into thinking that everything is going to be straightforward, even mundane.

But the truth is, I sometimes write a story in past, feel dissatisfied, and then rewrite the whole thing in present, just trying to strip it of those little adornments you always have room to add when writing in past tense. With me, past tense gives room for lyricism, for reflection. Sometimes that’s good, as in “Love Goes to a Building on Fire”; reflection is the whole point of that story. But if you want propulsion, immediacy, present tense is a good way to go.

I’ve never understood people who talk about the “artificiality” of present tense. People use present tense all the time in everyday life. If anything, the resurgence of present tense in literary writing seems to me to be an attempt to get some of that orality inherent in jokes and small stories onto the page.

Then there are your lists, in particular “One Hundred Characters.” Let’s talk a bit about how that story took shape.

That was just a very simply constraint: how could I write a story that contained a hundred characters? (And, also, a pun about word count.) Or, to be a little more technical, how could I maintain a reader’s interest in a story that was essentially just a bestiary of everyday life in Philadelphia? I’ve always liked lists, because they seem to me to be about trying to reckon with the multiplicity of existence, and get as much of it onto the page as possible. I just finished reading a lovely review of Robert Browning’s literary career in which the writer suggested that Browning was overwhelmed by just how much stuff there was in existence—and it isn’t as if there are fewer things now than there were at the turn of the 20th century. No wonder list stories have become more popular; they’re sort of a way to get as much life into the narrative as possible, to clear out the mechanisms of plot and just let these living creatures do their thing.

That was just a very simply constraint: how could I write a story that contained a hundred characters? (And, also, a pun about word count.) Or, to be a little more technical, how could I maintain a reader’s interest in a story that was essentially just a bestiary of everyday life in Philadelphia? I’ve always liked lists, because they seem to me to be about trying to reckon with the multiplicity of existence, and get as much of it onto the page as possible. I just finished reading a lovely review of Robert Browning’s literary career in which the writer suggested that Browning was overwhelmed by just how much stuff there was in existence—and it isn’t as if there are fewer things now than there were at the turn of the 20th century. No wonder list stories have become more popular; they’re sort of a way to get as much life into the narrative as possible, to clear out the mechanisms of plot and just let these living creatures do their thing.

Did working on The Great American Songbook overlap or dovetail with another major writing project? And what are you working on these days?

Well, considering that these stories have been percolating for nine years, several writing projects. I’ve written two novels in that span of time, neither of them published, and several other stubs of novels which never quite became functional. To be honest, I never thought this collection would be my first book. I’ve always loved writing short stories—I’m sort of addicted to the form, really—but I put a great deal of work into those two novels, and it was a disappointment when neither of them panned out. I’m working on another one now, which seems, at least at this point, to be better than the ones I wrote before—although my personal opinion on whatever writing project I’m currently working on has a way of being fickle!

This book was published less than a week after the 2016 presidential election. Are the election results and Trump’s transition into power changing the sense you have of your role in the world as a writer and writing teacher?

I think we’re all still in the grieving process. My hardest work over the last month has been trying to deal with the emotional needs of my students, most of whom can’t believe that Trump won, and many of whom are legitimately frightened for themselves and/or their families. It’s too early to tell how my work will change, although I can’t imagine it will become less political. To be honest, it’s been odd having a book out, odd promoting it, odd looking at all of these stories that were written at the beginning of the Obama years, while this massive transformative shift is occurring on the national scene. We’re going to need art and literature more than ever in Trumpland, but it will be a different kind of art, to suit the times, and I’d be lying if it wasn’t a bit bittersweet to read these stories over, a few days after to the election. The first story was published in the twilight of the Bush years, and the book came out at the very end of the Obama era, an era which—although it was disappointing, and ultimately fell short in so many regards—seemed, at the time, to represent a change in the way America saw itself. I believed in this change, like many of us did, and ended up being disappointed—and now here we are, with something much worse. Looking at the stores from that time, considering what’s happening now, feels a little bit like saying a firm goodbye to my youth.