Forty years ago James Dickey published Deliverance, a whittled-down novel about four suburban men who venture into the woods of the south, coming up against the local residents, a vicious river, each other, and themselves. They didn’t come out well. Dickey’s novel harkened back to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, another novel about a “civilized man” who enters the jungle and comes up against the wilderness and his own dark nature.

Forty years ago James Dickey published Deliverance, a whittled-down novel about four suburban men who venture into the woods of the south, coming up against the local residents, a vicious river, each other, and themselves. They didn’t come out well. Dickey’s novel harkened back to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, another novel about a “civilized man” who enters the jungle and comes up against the wilderness and his own dark nature.

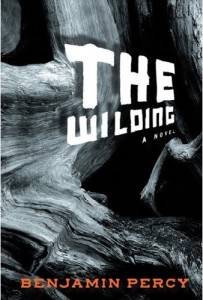

Both of these works are referenced in Benjamin Percy’s new novel, The Wilding, which released this week from Graywolf Press, the earlier in an epigraph (“I felt as though I had dipped into some supernatural source of primal energy”) and the latter as an assignment given to one of the main character’s high school students. And it’s no accident. As Publishers Weekly labeled it, The Wilding is a modern-day Deliverance, set in a time when our planet is taxed more than ever. The novel tells the story of three men from one family—a son, father, and a grandfather—who venture into the woods for one last visit to a wildlife preserve before it’s chopped down and paved over to make room for a new development. They come up against the locals, who can’t help but think of them as city folk; a possibly ancient and predatory animal, who might want to kill them; and their own natures—the son learns to shoot a gun and be a man in his grandfather’s image, the father struggles with this while worrying for his son’s safety, and the grandfather grows closer to his family while denying a weakening body. Meanwhile, back in town, a veteran becomes obsessed with the father’s wife, who is trying her best to cope with a miscarriage. As the novel picks up, it reads like a thriller. And by the end it will come to an inevitable head, with both the Oregon wilderness and Percy’s characters having been put to the test.

Readers of Percy’s two story collections (Refresh, Refresh and The Language of Elk) will recognize the lyrical language describing Oregon’s landscape and the emergent theme of man’s relation to himself, his work, and his family, which have always wound their way into his work. But here, in his first novel, Percy takes those thematic and stylistic strengths and builds upon them by introducing a multi-voiced narrative. So what we get through the collective telling of this book is not simply an individual’s tale, but a panoramic view of the classic story of man versus nature.

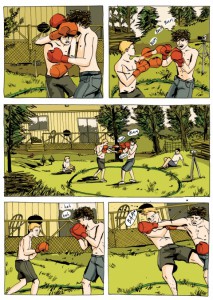

Percy’s fiction and nonfiction have been read on National Public Radio, performed at Symphony Space, and published in Esquire, Men’s Journal, The Paris Review, Chicago Tribune, Orion, Ploughshares, Glimmer Train, and elsewhere. His honors include a Whiting Award, the Plimpton Prize, a Pushcart Prize, and inclusion in Best American Short Stories. His story “Refresh, Refresh” was adapted into a screenplay by filmmaker James Ponsoldt and a graphic novel (First Second Books, 2009) by Eisner-nominated artist Danica Novgorodoff.

After we met at AWP in Denver this year, and again at the Little Grassy Literary Festival at SIU–Carbondale, where he earned his MFA and I am pursuing mine, Benjamin Percy took time out of his busy schedule as a teacher, father of two, and prolific writer and freelancer to answer some questions regarding his forthcoming novel and how he balances it all.

Interview:

Shawn Mitchell: Your first novel, The Wilding, is on its way to readers, but I’d like to start by having you talk a bit about your short fiction. How did you begin writing stories?

Benjamin Percy: I’m not the kind of person who announced in the uterus that I was going to be a writer and then crayoned stories all the way through elementary school. I grew up with a terrible hunger for books, but pursued the sciences as a trade. Archaeology, geology—these were my proposed majors, my internships. It wasn’t until later in college—when I was working a summer job at Glacier National Park, where I met my then girlfriend, now wife, Lisa—that I considered writing as a pursuit. For her I scrawled out all of these poems and love letters, and she said to me, “You should be a writer,” and I said, “Okay.” And that’s the reason, the only reason, I signed up for a creative writing class the subsequent fall. It would have never occurred to me otherwise. I was an undergrad at Brown, and Ben Marcus, now the head of the Columbia MFA program, was my first writing instructor. Aside from a short story written in a high school English class—about Conan the Barbarian time-traveling into the present day and getting into an epic battle with a group of skateboarders—I had never experimented with the form until then. I was awful, but I was hooked. I had always been a reader, but the books that filled my shelves had dragons and skeletons and cowboys on their covers. I didn’t know who Raymond Carver was—I had never read Sherwood Anderson or Alice Munro or Tim O’Brien. I had a lot of catching up to do. And so I spent hours every day reading and writing my ass off, focusing almost exclusively on short fiction, trying to understand its design.

What “hooked” you about the process, exactly?

The fierce immersion of reading, for one. My imagination is such that when I dive into a short story, whether it’s five pages or fifteen, I’ve taken an emotional and physical journey, I’ve lived another life. I am in Annie Proulx’s Wyoming, in Hemingway’s Michigan, in Flannery O’Connor’s Georgia. And these worlds take up residence in my head permanently, becoming a part of my consciousness, so that in a single afternoon of reading I can feel as though I have traveled, even matured.

And the perfection of the form. You can’t write a perfect novel, but you can write a perfect short story. There is of course something ethereal at work, but the mechanics of storytelling can be deconstructed, observed the same as any architect’s blueprint. Up to this point, I was mapping out excavated villages, itemizing bits of bone and shell into containers, methodically recreating history—and that training transferred well into strenuous reading and writing.

And there’s something about my mind—the hard-wiring of it—that made short stories a natural fit. I have always had an uncanny ability to concentrate. I can go deep into my mind for hours and not realize that I am punching keys on a computer. If I have an open schedule, I can, in a manic imaginative rush, produce a good workable draft of a short story in two days (which will then of course have to be refined). I was a sprinter in high school, and the process of writing short fiction—the rush of wind in my ears, the finish line in sight, every step so essential, every muscle fiber tensed into motion—appeals to the sprinter in me.

Your prose style manages to blend hard-lined syntax with looser, more lyrical passages. Were there any writers who were particularly influential as you developed your early prose style?

Early on, I went through obsessive binges: Flannery O’Connor, Rick Bass, Denis Johnson, Barry Hannah, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Raymond Carver, Cormac McCarthy, Harry Crews, Daniel Woodrell. I would read everything the author had published—immersing myself in their work for months on end—and during this time, I would ape their style. I see this as an essential growth period and encourage my students not to resist mimicry; so often I hear from them, “I’m not reading anything right now—I don’t want my writing to be influenced.” Reading Blood Meridian over and over and trying to write like McCarthy is no different than a ball player studying footage of Albert Pujols and changing their batting stance, or a painter setting up an easel in a museum and trying to match the brush strokes of a Monet. You acquire all of these tricks—opening stories with a wide shot, ending a story in the future tense, employing repetitive dialogue, whatever—that over time become a stylistic arsenal you make your own. I tend to make my action scenes more hard-clipped and moments of reflection and transition more lyrical—and see this move as a blend of devices drawn from McCarthy, Bass, Carver, and Crews.

Early on, I went through obsessive binges: Flannery O’Connor, Rick Bass, Denis Johnson, Barry Hannah, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Raymond Carver, Cormac McCarthy, Harry Crews, Daniel Woodrell. I would read everything the author had published—immersing myself in their work for months on end—and during this time, I would ape their style. I see this as an essential growth period and encourage my students not to resist mimicry; so often I hear from them, “I’m not reading anything right now—I don’t want my writing to be influenced.” Reading Blood Meridian over and over and trying to write like McCarthy is no different than a ball player studying footage of Albert Pujols and changing their batting stance, or a painter setting up an easel in a museum and trying to match the brush strokes of a Monet. You acquire all of these tricks—opening stories with a wide shot, ending a story in the future tense, employing repetitive dialogue, whatever—that over time become a stylistic arsenal you make your own. I tend to make my action scenes more hard-clipped and moments of reflection and transition more lyrical—and see this move as a blend of devices drawn from McCarthy, Bass, Carver, and Crews.

So do you think that young writers are overly concerned with “originality” and developing a “voice”? And, if so, what should they be thinking about instead?

Of course everyone wants a voice—wants to be distinctive—and this will happen in time. But first you have to study and acknowledge the admonishing presence of those who came before you. One of the best ways to do that, to understanding how an author produces a certain visual effect or captures a certain dialect, is through immersive mimicry.

Last year I took Beth Lordan’s workshop here at SIUC, where you also received your MFA. She had us each do a twenty-minute explication of how one short story was working on a craft level. Preparing for that explication was a helpful process for me, and I’m hoping to take her forms class before I complete the program. You’ve mentioned that you like to pick apart favorite short stories for how they’re working, how they’re shaped, blow-by-blow. That sounds a lot like her approach. Was that something you learned from her as a student?

Beth Lordan taught my first graduate workshop, and I had that same assignment, explicating “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried,” by Amy Hempl, which is a story I adore now but didn’t understand then. I didn’t understand many things then. Point of view, for example. When I jumped into grad school, I knew there was first, second, and third person. Simple as that, right? I, you, he. I had never thought about first person peripheral vs. first person central. I had never considered what it meant to have an unreliable narrator. I had no idea the difference between omniscience and limited omniscience and close third and objective. I didn’t understand why I couldn’t jump from one character’s head to another mid-scene. Etc. Assignments like this one, which were frequent with all of my grad school instructors, including Brady Udall and Mike Magnuson, forced me to look closer. I began to read stories three or four times. The first for emotional engagement—for the vivid and continuous dream Gardner speaks of—and then for the nuts and bolts. I became a careful carpenter studying blueprints, every word a 2×4, every punctuation a nail driven by a hammer. On occasion, if I truly admired a story, I would scribble out its design in a yellow legal tablet. Paragraph One: Character A introduced in job-related action that reveals personality; Setting at war with character and creates sinister mood; Theme hinted at in last sentence via weather and lighting. And on and on, blow-by-blow, like you said. And then I would try to borrow that skeleton and paste my own flesh upon it, creating an entirely different story with the same beats. That was a great learning experience.

Listening to you talk about how you “studied” fiction, and considering the fact that you teach at Iowa State University’s MFA program, I assume that you believe writing can be taught. Is that true?

Passion can’t be taught. Vision can’t be taught. Ideas can’t be taught. But craft can.

Speaking of MFA programs, you refer to the stories in The Language of Elk as your “graduate school stories”? Do you feel that something marks those stories as, say, products of pursuing a degree in creative writing? Or did you simply mean that those were the stories that helped teach you write?

Speaking of MFA programs, you refer to the stories in The Language of Elk as your “graduate school stories”? Do you feel that something marks those stories as, say, products of pursuing a degree in creative writing? Or did you simply mean that those were the stories that helped teach you write?

I mean that they’re stories I punched out when I was twenty-three and twenty-four. They’re raw. Some of the sentences are pretty, but some of them make me cringe. Some of the characters feel alive, and some of them feel like sketches. When I look back at that book, I see a toddler finding his balance, sometimes sprinting, occasionally falling on his ass. “Swans” is the transitional story in that book—the story that is closest to the more muscular work I’m doing in Refresh, Refresh.

What happened differently with “Swans?” Where did that story come from?

That story came out of a bet. I was at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference in 2003 as a Tennessee Williams Scholar, palling around with the likes of Dean Bakopoulos, Tony Earley, Richard Bausch, Barry Hannah, William Giraldi, and FWR’s own Jeremy Chamberlin. A few of us became very tight, and one silly, drunken night the town of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, became a running gag among us. It was the sound of the word—Murfreesboro—that we loved so much, the way it slurred off the tongue. Like any inside joke, this isn’t going to make much sense to somebody who wasn’t there. But we all made a promise to each other: we would hammer out a story that makes reference to or takes place in Murfreesboro. Just to get that word in there. These stories are all out there in the world. “Swans” is one of them.

That, of course, doesn’t explain what happened differently with this story. I’m not sure how to answer that. I just moved to the next level, like a snake pushing through a layer of skin. This was the beginning of my third year in grad school—I had been reading and writing every day—for several hours a day—for two years straight. And if you keep practicing, you get better. This story had more muscular sentences, an elliptical structure, a magical realist tone, and an explosive, inevitable ending that I hadn’t managed before then.

While visiting us here at SIUC for our Little Grassy Literary Festival this past spring, you mentioned that graduate school was an anxious time for you. Can you clarify what you meant? I ask because I feel the same way.

During orientation, Mike Magnuson said to the group of us, “If you look at the percentages, you have a better chance of making it as a major league ball player than you do as a writer.” That’s where the anxiety began. I had no idea of what I was getting into, no idea the hard work in store for me. I’m somebody who wants to be the best—and I knew that I wasn’t even playing minor-league ball then (I was the guy in the stands, keeping score, wearing the jersey and the beer helmet). I was married then, and my wife had quit a good job and traveled across the country to support my ass while I attended grad school. I knew I wasn’t at the best program in the country, and I knew I was less talented than most everyone in my cohort. I needed to step up. The faculty handed out a list of 100 books I ought to have read—maybe three of them were familiar to me. But within a year, I had every one of them in my library, scrawled over with inky notes. I started waking up at 4:30 AM and writing until 3 PM every day. I started submitting widely and stubbornly to magazines. At first the anxiety was, am I good enough? And then, after I started publishing in magazines and winning awards, I began to worry about when I would publish a book. And then, as those three years rushed past, I began to worry about work, what I would do after the MFA—get a teaching job, pursue a PhD, move overseas, bartend while trying to finish a novel. So many things were up in the air—and all of these possibilities were swirling through my head constantly—I’m surprised I didn’t end up with a stomach riddled with ulcers.

I know what you mean. It’s a great gift to be here, but every year presents new anxieties. How did you balance that writing schedule with your teaching schedule here? I try to streamline the process as much as possible while still being helpful to my students, but sometimes this cuts into my writing and reading time more than I’d like. This is especially true with Intro to Creative Writing, which I’m teaching this semester.

I always tell my grad students, you’re here to write. Which isn’t to say that they should do a bad job teaching comp, of course, but they shouldn’t do a great job. Here’s what I did. I kept crazy good notes. Everything written out and filed away. So after my first year, I had no prep. I could look at my notes ten minutes before class and feel ready to go. Grading is of course a major time suck. And here’s what I noticed: some of my comp students would leave class with their paper, check the grade, and then toss it in the garbage. So I gave extensive marginal notes on the first page, no more. And then I wrote out three general/comprehensive comments at the end. And signed off with “See me if you have any questions.” And they would. If they really cared about their grade and the class, they would come to see me during office hours and I’d take them paragraph by paragraph through the essay. I also kept a watch nearby when grading. I wouldn’t allow myself more than twenty minutes per paper.

I always tell my grad students, you’re here to write. Which isn’t to say that they should do a bad job teaching comp, of course, but they shouldn’t do a great job. Here’s what I did. I kept crazy good notes. Everything written out and filed away. So after my first year, I had no prep. I could look at my notes ten minutes before class and feel ready to go. Grading is of course a major time suck. And here’s what I noticed: some of my comp students would leave class with their paper, check the grade, and then toss it in the garbage. So I gave extensive marginal notes on the first page, no more. And then I wrote out three general/comprehensive comments at the end. And signed off with “See me if you have any questions.” And they would. If they really cared about their grade and the class, they would come to see me during office hours and I’d take them paragraph by paragraph through the essay. I also kept a watch nearby when grading. I wouldn’t allow myself more than twenty minutes per paper.

This was comp, not creative writing. When I was a grad student teaching creative writing, I put a hell of a lot of effort into that class because I cared about the material so deeply. And —same as today—I discovered that I improved as a writer because of my teaching, because I had to take apart these stories and understand them better than anybody in the room.

During that same festival, you were asked about the portrayals of masculinity in your work. It seems like you get this question a lot. Is it ever frustrating to have your work so identified by a particular characteristic? Or do you actively strive to explore what it means to be male?

Oh, people are always whining about being labeled a Southern writer or a sci-fi writer or a writer of women’s fiction. We love to categorize, and one of the categories I’m associated with is the “Neo-Masculinist” movement. I’m not sure what that means—though if people want to read me that way, fine. I’m not intentionally trying to explore maleness, and I know anything I say on the subject is going to come across as bullshitty intellectualism. I’m just trying to write good stories, and the place those stories come happens to be hairy and sweaty and snarled with barbed wire. When you get down to it, I’d rather move peoples’ hearts than their heads.

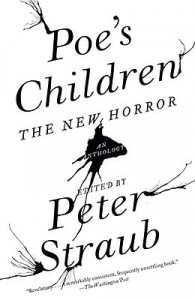

Is that why elements of “genre” fiction often make their way into your work? Your story “Unearthed,” involving a father and son who dig up the corpse of a Native American, was even included in Peter Straub’s anthology of new fiction, Poe’s Children. Did you read a lot of genre fiction, horror in particular, when growing up?

Everybody grows up on genre, whether westerns or romances or spy thrillers or horror. That’s what makes us fall in love with stories—the comforting familiarity of the tropes and design, the rip-roaring plots. I grew up reading Tales from the Crypt comic books, FANGORIA magazine, Stephen King, Peter Straub, and though my interest in the genre never died, when I found myself in undergraduate and graduate workshops, I felt so behind on literary fiction that I read it exclusively for years, scrambling to catch up with my classmates. I did try, on a few occasions, to hand in some genre stories to workshop and was ripped apart for it. So it wasn’t until I left grad school that I began to experiment with the form, approaching it with a literary arsenal, so that the end product is neither fish nor fowl, hard to categorize. But if you look closely at my stories, you’ll see that “Crash” is a ghost story, “The Caves in Oregon” is a haunted house story, “Meltdown” is a western, “When the Bear Came” is a monster-in-the-woods story, “The Killing” is a pulpy tale of revenge. Horror is the genre I’m drawn to most viscerally—and the novel I’m now writing (tentatively titled Red Moon) is an outright horror novel.

Everybody grows up on genre, whether westerns or romances or spy thrillers or horror. That’s what makes us fall in love with stories—the comforting familiarity of the tropes and design, the rip-roaring plots. I grew up reading Tales from the Crypt comic books, FANGORIA magazine, Stephen King, Peter Straub, and though my interest in the genre never died, when I found myself in undergraduate and graduate workshops, I felt so behind on literary fiction that I read it exclusively for years, scrambling to catch up with my classmates. I did try, on a few occasions, to hand in some genre stories to workshop and was ripped apart for it. So it wasn’t until I left grad school that I began to experiment with the form, approaching it with a literary arsenal, so that the end product is neither fish nor fowl, hard to categorize. But if you look closely at my stories, you’ll see that “Crash” is a ghost story, “The Caves in Oregon” is a haunted house story, “Meltdown” is a western, “When the Bear Came” is a monster-in-the-woods story, “The Killing” is a pulpy tale of revenge. Horror is the genre I’m drawn to most viscerally—and the novel I’m now writing (tentatively titled Red Moon) is an outright horror novel.

It’s a shame that we do that in workshops: we make it clear that “literary” fiction is the only way to learn to write well, and ban “genre” completely. I’ve been trying to not do that in my own class, and trying instead to emphasize good writing and allow “genre” elements, something that Pinckney Benedict emphasized in our workshop last semester. But I also know that if these students move on into other creative writing courses, they might come across a teacher who discourages these things, even though there are a huge number of successful writers toying with or ignoring the line between “genre” and “literary” fiction, and there always have been, really. Do you actively encourage students to allow “genre” elements into their stories? Or do you see a pedagogical advantage to limiting their range during their earliest classes?

I don’t limit their range. They can write in any genre they want. But I advocate a hybrid approach. So if they’re writing sci-fi, I’m demanding three-dimensional characters, a strong sense of setting, muscular language, etcetera, the same as if their story took place in a suburban neighborhood and concerned a messy marriage.

In your recent essay on revision in Poets & Writers, “Home Improvement: Revision as Renovation,” you called an earlier draft of The Wilding a “shnovel,” a short story posing as a novel, which you had to edit intensely with the feedback from your editor, Fiona McCrae. Outside of her editorial belief and involvement, what do you think made this story leap from “shnovel” to novel while the others “turn[ed] to dust,” as you put it?

I don’t know how many failed short stories I wrote, maybe dozens, before one of them took flight, but I can tell you how many failed novels I produced before selling one: four. I made mistakes and I learned from them. Failed short stories are much easier to learn from than novels: in a matter of days or weeks, you can point your finger at the problem(s). These longer projects took several years to reveal their warts and boils. So I learned—with stores of patience—what I was doing wrong. My first novel was emotionally juvenile and conceptually weak. My second novel was written with the intense, hyper-lyrical language of a short story, which exhausted the reader. My third novel took too many risks, which sacrificed believability. My fourth novel was structured like many of my short stories—in an elliptical fashion—which made it feel stalled, without momentum. There wasn’t a causal sense of plot.

I don’t know how many failed short stories I wrote, maybe dozens, before one of them took flight, but I can tell you how many failed novels I produced before selling one: four. I made mistakes and I learned from them. Failed short stories are much easier to learn from than novels: in a matter of days or weeks, you can point your finger at the problem(s). These longer projects took several years to reveal their warts and boils. So I learned—with stores of patience—what I was doing wrong. My first novel was emotionally juvenile and conceptually weak. My second novel was written with the intense, hyper-lyrical language of a short story, which exhausted the reader. My third novel took too many risks, which sacrificed believability. My fourth novel was structured like many of my short stories—in an elliptical fashion—which made it feel stalled, without momentum. There wasn’t a causal sense of plot.

I also hadn’t approached novels with the same studiousness that I did short stories. Earlier I mentioned that I would read the same short story over and over and make notes as to how its pieces fit together. I never did the same with novels, until these past three years. Previously, when I was pursuing these longer projects, I was often reading short stories, the style and the structure of which I should have been avoiding.

One of the most dramatic changes you described undertaking during the revision process was rewriting the entire book in third person, after completing it originally in a first-person point of view. How did you know this was the right decision?

Have you ever watched the extras on a DVD? Sometimes they show you a deleted scene. There’s no music, no editing, no effects. Often it’s a single wide shot, and you can see the potential of the moment, but it isn’t quite there. You need a more complex orchestration. The violins need to rise in the silence that follows a sinister line of dialogue. The camera needs a close up on an expression when a character makes an irrevocable decision. The ectoplasmic ghosts needs to be CGI’ed into the moment if we’re actually going to feel as afraid as the characters seem to be. In that original draft, I had the basic storyline, but I didn’t have that kind of layering. The jump to third person allowed me to approach the animalistic core of the story from several different angles, making it more complex and dynamic—an honest-to-goodness novel.

Toward the beginning of the novel, when characters are being introduced, the first thing discussed is most often their occupation and the routine and habit of thought that comes along with that. Karen is a school dietician, Justin an English teacher, Bobby Fremont a developer, etc. This has been an ongoing concern in your stories as well—how occupation defines character. So is this a short-hand for the reader, or are you using it to uncover the characters yourself as you write?

I’m presently writing a craft article about this same subject for Poets & Writers called “Get a Job.” Too often, writers forget that work defines us. We spend most of our days hunched over a sizzling grill at a family-themed restaurant or pulling a lever at a bullet factory or punching numbers into a keyboard while sitting in a cubicle at an accounting office. My father-in-law, even when he’s on vacation, is talking about farming, glancing out the window along the Interstate, studying the crops, the machinery grumbling through the fields. I try to bend the world around the job. If a character is a piano mover—as Kevin McIlvoy teaches us in his short story “The People Who Own Pianos”—the world is broken down into a series of tight hallways and narrow staircases and the world becomes a place where you’re either the type who owns or moves pianos. Everything about the point of view, as you’re following one of my characters, is filtered through this mindset. I’m really simplifying things here, but if you look at Karen, the dietician, she views the world according to its nutritional value—and she comes to see her husband almost as a toxin she must expel from her body. Or Bobby, the developer, who looks to own and conquer most everything he comes across, people included.

Another trend of your work seems to be that your stories often develop around a pattern of images and occurrences that lend them a kind of a “theme” (or “subtle thesis,” if you’re teaching composition here at SIUC). The same thing happens in the novel. Your three epigraphs have to do with wildness, father-son relations, and how people are changing the landscape, and throughout the novel these themes reappear, often all at the same time. Did these themes develop naturally over the course of the book, or did you set out deliberately to explore them?

It’s dangerous to begin a story with a thematic agenda. The story will feel unnatural, forced, will read like an editorial or after-school special. I chase images. I chase characters. And eventually, as I build a story, as I polish my sentences to a glow, I notice patterns and begin to understand what the story is About. Capital A. I’m not talking about plot—I’m talking about how the plot will transform the characters and the reader. So writing is first an instinctual and then a deliberate process.

You’ve got this novel coming out. Stories keep popping up in magazines. You teach at Iowa State University and in the low-res MFA program at Pacific University. You contribute to Esquire and other publications. How do you balance it all and still find new material and time to work on your fiction? How do you stay in the ring, to reference another of your P&W articles?

You’ve got this novel coming out. Stories keep popping up in magazines. You teach at Iowa State University and in the low-res MFA program at Pacific University. You contribute to Esquire and other publications. How do you balance it all and still find new material and time to work on your fiction? How do you stay in the ring, to reference another of your P&W articles?

You’re forgetting the hardest job of all: I’m father to two young children. I don’t sleep: that’s the answer. Five hours a night sometimes. My blood type is caffeine. I never take it easy—I’m always working, always writing or editing or grading. Even when I’m supposedly relaxing, I’m not. If I’m at the gym, I’m listening to an audiobook. If I’m watching a movie, I’ve got my notebook out and I’m jotting down ideas. If I’m out in the yard with my kids, I’m pushing around sentences in my head. People often seem to view writing as an indulgence, but I operate under the belief that you must give up all indulgences if you want to write seriously. I used to think this was a calling—that’s too romantic of a term. I’m fairly certain that I’m driven by obsession.

In addition to staying busy teaching and writing fiction, you also write a lot of nonfiction. In particular, journalism for magazines. Your Facebook profile makes it seem as though you’re always on another assignment: living in a tree, covered in bees, hang gliding. How does this type of work relate to your fiction?

I like the idea of being a writer in the trenches. Seeking out new, thrilling experiences to inform the quiet, routine work I do at the keyboard. Research is essential, I tell my students. If I’m writing about a taxidermist, I visit a studio, finger the glass eyeballs, smell the chemicals, speak at length to the workers and try to acquire some sense of their specialized language and perspective. This is intentional research. But I also do accidental research—I go stumbling around, trying to soak up new experiences. I jump out of planes. I open up bee hives. I eat Rocky Mountain oysters. I strike up conversations with strangers. Every time I take a trip—whether it’s for a nonfiction assignment or for pleasure—I come away with dozens of story ideas. If I sat at home all day, my imagination would grow rather claustrophobic. I like to be out in the world, my mind open, so that whatever is swimming by will have a chance to swim in.

What about in terms of the actual craft of your fiction? Does writing nonfiction make you a better storyteller, for example? Or force you to learn to be more concise?

What about in terms of the actual craft of your fiction? Does writing nonfiction make you a better storyteller, for example? Or force you to learn to be more concise?

I’m using the same tricks, mostly, in nonfiction and fiction. Nonfiction I have a word count, so I suppose you could say it makes me more concise. Working for magazines has also taught me to readily let go, to cut hundreds, sometimes thousands of words, because the graphic designer wants to include some artwork or because the editors need to fit a larger advertisement onto the same page. You can’t have much of an ego writing (magazine) nonfiction: it’s a much faster turnaround, a much harsher edit, a much different audience. “Quit being so fucking literary,” is a common edit I get with the glossies.

You’ve mentioned that you like to keep a list of craft goals tacked up on a bulletin board along with notes on character, image, dialogue, like “write a story in second person.” Are there any of those challenges that you want to tackle soon?

I glance at that bulletin board every day. It’s also crowded with images, strips of dialogue, metaphors I hope to one day use. At least once a month, two or three things tacked up there emerge like a constellation and I realize how they come together as a story. And yeah, I’ve got rhetorical/grammatical challenges up there as well. Write a first person plural story is one of them—a voice that turns out to be the voice of the town gossip.

To close, what’s the best advice that you can give young writers?

Read your brains out, write your brains out. This is a long, painful apprenticeship and those who make it make it on equal parts stubbornness and talent.

Further Links and Resources:

- For more work and news from Benjamin Percy, please visit the author’s website.

- You can also listen to Percy read “Heart of a Bear” for Orion

- Read Percy’s recent story in Esquire, entitled “Keep Doing What You’re Doing, James Franco.”

- Find links to Percy’s craft essays for Poets & Writers here.

- For more of Danica Novgorodoff’s work, including images from her graphic novel adaptation of “Refresh, Refresh,” please visit the artist’s website.

- You can also watch the book trailer for the graphic novel, which was adapted from Novgorodoff’s work: