I had a teacher once who used to talk about the “well-made story” as if it were a bad thing. Technical mastery, he suggested, was nearly synonymous with emotional anemia. To be really great, and really truthful, a story had to be messy and excessive; to be perfect, it also had to be flawed.

I’ve known for a long time that I disagreed with this, but it took Andrew Porter’s debut collection, The Theory of Light and Matter, to help me figure out exactly why. These are, in every sense, well-made stories–beautifully paced, full of lovely sentences that you’ll want to read aloud just for the pleasure of it. But Porter’s technique is not a substitute for emotional depth or story. The placid surfaces of his characters’ lives crack open when the reader least expects it. Holes, both literal and figurative, open up in unexpected places. Appearances are deceptive, and miscommunication leads to tragedy. These stories are not objets d’art, but nested boxes. Their surface beauty leads us deeper, toward hidden and surprising truths.

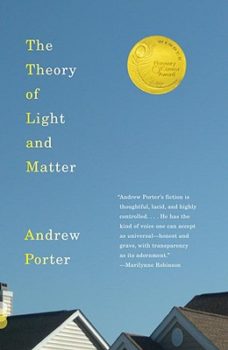

Andrew Porter is the author of the short story collection The Theory of Light and Matter, which won the 2007 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and was recently republished in paperback by Vintage/Random House.

Foreign editions of The Theory of Light and Matter have also been published in both the UK and Australia, and will be published in translation in France, The Netherlands and Korea. In addition to winning the Flannery O’Connor Award, The Theory of Light and Matter also received Foreword Magazine’s 2008 Book of the Year, was long-listed for The Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, and was selected by both the Kansas City Star and the San Antonio Express-News as one of the Best Books of 2008.

A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Porter has had stories published in One Story, Epoch, The Pushcart Prize Anthology and on NPR’s “Selected Shorts.” He currently teaches at Trinity University in San Antonio. I first met him in the late nineties, when we worked together at the Center for Talented Youth at Loyola Marymount University. This interview was conducted by email in May-June 2010.

Interview

Polly Atwell: In Time Out New York, David Levinson called you “a rubbernecker with a gimlet eye.” Do you consider yourself a rubbernecker? Are most of your stories informed by something you’ve actually observed?

Andrew Porter: That’s always a tough question to answer. On the one hand, the plots and the characters in my stories are completely fictional, but on the other hand, a lot of the small details that inform the plot and make up the characters aren’t. For example, I might have a character who embodies several qualities of people I’ve known and the details of this character’s life might be connected to places I’ve lived, jobs I’ve had, or stories I’ve heard, and so at a certain point it becomes hard to know where to draw the line between observation and imagination. My imagination may have created a particular character, but more likely than not the details and personality traits that make up this character are rooted in things I’ve observed.

The first story in your collection, “Hole,” is told by an adult remembering a traumatic event of his childhood, when his best friend and neighbor disappeared into an abandoned sewer in his backyard. This story could have been told in linear form and present time, but you chose to give a retrospective dimension, and also an element of unreliability–the narrator tells us that he tells the story differently every time, so we’re not completely sure that the story he’s telling us is the true one. Can you talk about how you arrived at these structural decisions?

In writing “Hole,” I think I realized early on that this was going to be a story about memory and the way our minds reconstruct memories, particularly memories of traumatic events, and so I wanted to use a non-linear structure that kind of mirrored this process. In other words, I think I wanted the structure of the story to tell us as much about the narrator as the story itself—the fact that he keeps repositioning himself, jumping around in time, approaching the event from different angles. In my experience at least, this is the way most people’s minds work, at least when they’re trying to remember something traumatic. And I don’t know that I could have achieved this effect as well had I simply used a linear approach.

The review of Theory… in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution suggested that the development of your style had a lot to do with the tradition of the short story associated with your alma mater, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. How do you think that Iowa–both your experience there and the literary tradition it represents–has influenced your work?

I think my two years at Iowa were probably the two most important years in my life, at least in terms of my development as a writer, though this wasn’t because I was producing a lot of work while I was there or because the work itself was particularly good. I think it had more to do with the fact that I was surrounded by so many other people who were serious about writing and who worked extremely hard to produce good work. I’d never been around so many serious writers before, and it had a very profound effect on me. As for the tradition of the program, all I can say is that we were all very aware of it, of course, and while it may have created some anxiety at times, it also probably made us work even harder.

I think my two years at Iowa were probably the two most important years in my life, at least in terms of my development as a writer, though this wasn’t because I was producing a lot of work while I was there or because the work itself was particularly good. I think it had more to do with the fact that I was surrounded by so many other people who were serious about writing and who worked extremely hard to produce good work. I’d never been around so many serious writers before, and it had a very profound effect on me. As for the tradition of the program, all I can say is that we were all very aware of it, of course, and while it may have created some anxiety at times, it also probably made us work even harder.

Which writers were you encouraged to read at Iowa? What lessons did you learn from them?

I can’t remember any of the professors encouraging us to read specific writers, but I know that I was introduced to the work of a lot of new writers through conversations with friends. In fact, I think I thought I was pretty well read before I arrived at Iowa, where I met people whose personal libraries put mine to shame. Anyway, there were definitely certain writers who people were talking about—young writers, like Junot Diaz, who was just starting out, and recent graduates of the program, like Nathan Englander, and Chris Adrien and Julie Orringer, who were just starting to get their stories in print. There was a lot of fascination with young success at that time, which is probably pretty typical in any MFA program.

Barry Hannah was a teacher of yours, and he provided a glowing blurb for your collection. What was it like working with him? How do you think that he will be remembered, as a teacher and a writer?

Barry was a real character and a wonderful teacher. Probably the funniest human being I’ve ever met, but when it came to workshop, he had an amazing critical eye. Maybe it came from decades of teaching, but he had this ability to see right to the heart of any story and to tell you exactly what needed to be done. And, of course, I have a lot of fond memories of hanging out with him during his time there, and I’m also very grateful for his friendship and his steady encouragement during some of those difficult years right after. To be honest, it’s kind of hard to sum up a person like Barry in a few short sentences, but I can tell you that he’s dearly missed by everyone who ever had the privilege of getting to know him.

Several reviewers have compared you to Carver, others to Cheever, and you’ve mentioned Dybek as an influence. Were there other writers you went back to when you were writing these stories?

Yes. Probably too many to name. Richard Bausch, Stephanie Vaughn, Tobias Wolff, Junot Diaz, Jayne Anne Philips. There were certain books, like Stuart Dybek’s The Coast of Chicago, that I probably pulled of my shelf at least once a week.

What is your favorite Dybek story?

That’s a fantastic story, but I’m curious about why you chose it. “Pet Milk,” like many of your own stories, brings together layers of narrative, and the last paragraph gives us three different time perspectives in the same moment. Is it partly that nostalgic quality in the story that appeals to you?

Yeah, I think that’s definitely a part of it, but I also like the fact that virtually nothing happens in that story. I mean, it’s just about a moment, a small moment, but it’s captured so beautifully and written so elegantly that it somehow works. In some ways I feel like that story is held together almost entirely by the language and the imagery—the swirling pet milk connecting to the King Alphonse drink and then connecting again at the end to the swirling image of the train. It’s almost like a poem in that sense, which I guess isn’t that surprising considering Dybek was a poet long before he was a fiction writer.

I recently heard Junot Diaz say that for him, the untranslated Spanish in his work represents the part of any book that has to remain a mystery–that can never be completely grasped, even by the best reader. Your stories contain a lot of what, for the lack of a better word, I’ll call lacunae–letters that are referred to but not included in the text, events that are described in such a variety of ways that the truth about them remains opaque. What do these figurative white spaces in the narratives mean to you?

When I finish writing a story, I always like for there to be certain unanswered questions. I want the reader to feel satisfied, of course, but I also like for certain things to remain unknown. I guess it’s simply my way of reminding the reader, and perhaps myself, that none of us can ever really know the “true” story, that there are always going to be certain unanswered questions.

In the story “Azul,” a couple hosting a teenage exchange student make a number of bad decisions that almost lead to the student’s death. However, the narrator in particular is so likable and honest that the reader may sympathize with him in spite of herself. Did you always know that things were going to go wrong for this couple, or is that something that became clear to you as you drafted the story?

That’s an interesting question. In the initial version of that story, which didn’t include the accident at the end, I kind of let the narrator and his wife off easy. The story still ended at the party, but it was a very quiet, almost meditative sort of ending. It wasn’t until later, after I showed the story to my girlfriend (now my wife), that I realized that the ending needed to be changed. I think what she said to me was something along the lines of “Are you really going to let this couple get away with acting like this?” In other words, where there was so much bad behavior, so much irresponsibility, there needed to be some consequences. And though I’m usually resistant to changing my endings once I’ve written them, I realized that this time she was absolutely right.

Is sharing the story you’re working on with friends and family usually part of your revision process? If so, could you comment on how that influenced another story in the collection?

My wife is probably my main reader at this point, and I basically show her everything. When she says something is finished, or when she says something is ready to be sent out, she’s always right. In fact, some of the stories in my collection—like “Departure” and “Connecticut”—might have never left my hard drive had she not been so enthusiastic about them. I tend to second guess myself a lot, and so it’s nice to have someone else there whose opinion you trust. As for another specific example, all I can say is that the stories that made it into the collection were generally those stories that got the thumbs up from her.

In my favorite story in the collection, “River Dog,” the college-bound narrator is told that his ne’er-do-well brother’s rape of a local girl “has nothing to do” with him–something that he clearly can’t accept. Many of your narrators are faced with a similar dilemma, unable to believe that they’re not somehow responsible for the tragedies and crimes they witness. Were any of these stories written from a different point of view in an earlier draft, and if so, why did you decide to change them?

To be honest, I can’t remember ever changing the point of view of any of these stories, though I have played around with the idea of writing additional stories from the perspectives of some of the secondary characters. I think once I arrive at a point of view I tend to stick with it. I may end up abandoning the story, but I never really change the lens through which I’m telling it.

Beginning fiction writers are often told not to have narrators who observe more than they act, because it’s not interesting to the reader. Of course if writers followed this advice, we wouldn’t have The Great Gatsby, or Tristram Shandy, or some of Alice Munro’s best stories. Why are peripheral narrators useful, both to you and to writers in general?

Frank O’Connor

That’s a great question. I often give that same advice to my own students, though of course I don’t always follow it myself. To be honest, I don’t know that it’s something I’m thinking about a lot in the early stages of writing a story. Usually I’m just trying to figure out who the character is, and what the character wants, and what might be troubling the character. And I guess often times what’s troubling the character is the very fact that he or she feels isolated or alienated within the world of the story. In other words, the peripheral perspective kind of grows out of the character’s conflict, or perhaps is the conflict, the fact that the character feels somehow on the periphery of his or her own world. This kind of relates to what Frank O’Connor argues in his famous essay “The Lonely Voice” —that short stories tend to be about outsiders and outcasts, people who feel alienated or marginalized within their immediate communities. So perhaps that’s one important advantage of this type of peripheral perspective—it can serve to underscore the character’s own sense of alienation—something that, say, a character like Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby certainly feels.

Many reviews of your collection have spoken about the themes and locales that recur in your stories, but there also seem to be some sentence-level echoes between them. There are several minor and major characters named Alex, for instance, and more than one character is described as “not right” in the head. How would you describe the common world that these stories inhabit? Did you think of them as linked, and if so, in what ways?

I never really thought of the stories as being linked, but it’s true that there are lots of echoes between them, thematic and otherwise. In some ways theses echoes—for example the repetition of the phrase “not right” in several of the stories—were things I only noticed after the collection had been published, when people brought them up to me. In other words, they were purely accidental, but I suppose on some level it’s not that surprising. I mean, there are so many things going on in our minds on a subconscious level, so many strange connections being made, so many common themes and images that keep reappearing, that it seems inevitable that these type of repetitions might occur.

You said in another interview that before you got serious about writing fiction, you wanted to be a filmmaker. When you write fiction, do you ever think about how you would shoot it as a film? Are there any other ways in which the language of film is useful to you as a fiction writer?

I don’t know that I’ve ever made that connection before, but I suppose on some level my process is very similar to a filmmaker’s process. I don’t write my stories in a linear way, for example. I tend to just generate a lot of raw content, and then go back later and piece it all together, much like a filmmaker goes back and edits a film. And when I think back on my early interest in film and becoming a filmmaker, I remember spending a lot of time thinking about scenes, scenes that weren’t necessarily connected to larger stories. I remember thinking about what type of lighting I might use, what type of music I might use, and so forth, even when I didn’t know how the scene itself might connect to something larger, and this is very similar to the way I approach fiction writing. I just start with small moments and build from there.

Are you also writing your novel in individual scenes, then revising those scenes as parts of a whole?

No, I actually wrote the first draft of my novel in a much more linear way. I went section be section, chapter by chapter, but within individual chapters I suppose I used a similar approach, generating a number of different scenes, or versions of a scene, before deciding how I wanted to piece the whole thing together later.

How is the novel going? When will it be out?

I have no idea when the publication date will be, but it’s going well so far. I recently completed a very rough draft of the novel and will be trying my best to finish a final draft by January. We’ll see. I tend to be pretty superstitious when it comes to talking about works in progress, but I can say that the novel is set in Houston and that it involves a family going through a crisis.

It seems to me that the position of many of your narrators, looking back on their own pasts with compassion, humor, and sympathy, is in some way analogous to the position of the teacher who may see in his students versions of his past self. You’ve been a teacher of creative writing for some time now. How does being a teacher affect your work, in positive and/or negative ways?

One of the great rewards of teaching for me has been seeing some of my former students actually begin their own careers. At this point some of my earliest students have already completed their MFA degrees and are now out in the world, publishing stories, picking up teaching jobs, going to the AWP Conference, giving readings, and so forth. And it honestly make me so happy to see this. And yes, this is partly because I remember myself at their age, and I see them going through the exact same things I went through, and I remember of course how exciting and how terrifying it was. And so I guess that’s one of the nice benefits of teaching for a certain number of years. You begin to see the results of your efforts, but you also remain in close contact with a younger generation of writers, and you begin to see your relationship with these students changing. After a while, they stop seeing you as a mentor and start seeing you as a friend and a fellow writer, and that in itself is inspiring.

One of the great rewards of teaching for me has been seeing some of my former students actually begin their own careers. At this point some of my earliest students have already completed their MFA degrees and are now out in the world, publishing stories, picking up teaching jobs, going to the AWP Conference, giving readings, and so forth. And it honestly make me so happy to see this. And yes, this is partly because I remember myself at their age, and I see them going through the exact same things I went through, and I remember of course how exciting and how terrifying it was. And so I guess that’s one of the nice benefits of teaching for a certain number of years. You begin to see the results of your efforts, but you also remain in close contact with a younger generation of writers, and you begin to see your relationship with these students changing. After a while, they stop seeing you as a mentor and start seeing you as a friend and a fellow writer, and that in itself is inspiring.

You’ve had the experience of hearing your work read by actors, both on NPR’s Selected Shorts and at an event at the Knitting Factory that included Rainn Wilson and Amy Brenneman, among others. What was it like to hear your stories read in voices other than your own?

To be honest, it was completely surreal, especially the actor event in Hollywood. To see someone like Eric Stoltz, who I’ve admired for years, or Justine Bateman, who I watched on TV as a teenager, read my work, it’s kind of hard to describe. But I also have to say it was very educational. I mean, you realize why these people are called professionals. I remember that Justine Bateman did a very humorous reading of the title story in my collection, a story that I’d never really considered very humorous before, and I remember realizing then how much could be achieved simply by pausing in the right places, by controlling your delivery. And so that was wonderful to see, another person reinterpreting my story in a way I’d never considered before.

Who are some fiction writers, past or present, who we should be reading but probably aren’t?

Two of my favorite short story collections—Mark Costello’s The Murphy Stories and Stephanie Vaughn’s Sweet Talk—have both gone out of print, and so if there’s any way you can track down a copy of either of those collections, I’d certainly recommend reading them.

And there are some wonderful collections that have come out in the past year—Lori Ostlund’s The Bigness of the World and Laura Van Den Berg’s What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us, for example—that really impressed me. And then of course, there are certain established writers who I’d always recommend—Dan Chaon, Charles D’Ambrosio, Julie Orringer, and Chang-rae Lee, to name a few.