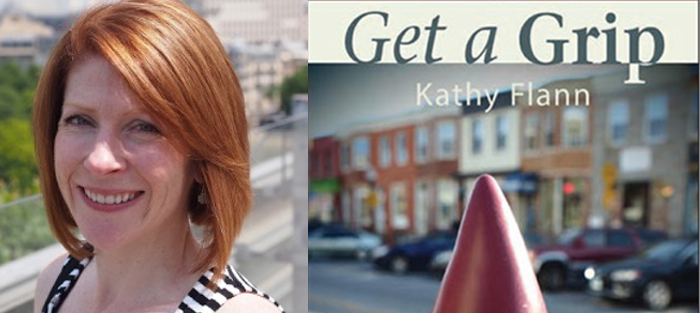

When Kathy Flann was getting her MA at Auburn, she worked in the library and read, cover to cover, every volume of Best American Short Stories, The PEN/O. Henry Awards, and other annual anthologies. She clearly loves the form, and excels at it.

Flann writes with a strong sense of place. Her first book, a collection called Smoky Ordinary, is set in an exurban, semi-rural town in Northern Virginia. It won the Serena McDonald Kennedy Award and was published by Snake Nation Press in 2008. Her second collection, Get a Grip, won the George Garrett Fiction Prize and is coming out this month from Texas Review Press. Get a Grip is, among other things, a mordant, richly comic tribute to Baltimore, a city she has grown to love, and its quirky inhabitants.

In addition to her MA, Flann also received an MFA in Fiction from UNC – Greensboro. She is currently a professor of creative writing at Goucher College.

Kathy and I met in 2009 at the Owl Bar in the Belvedere Hotel in Baltimore. We’ve been in two writing groups together—one fruitful, the other treacherous. She’s a wonderful friend and a terrifically sensitive editor. Both of us, like many writers of a certain vintage, are fretfully techno-deficient. For this taping, Howard Yang, Kathy’s husband, remained within earshot to assist us with file creation, uploading, volume control, and the like. Thank you, Dr. Yang.

Interview:

James Magruder: I remember your telling me soon after we met that you couldn’t begin a story until you knew everything about your characters. That was such an alien concept to me at the time. Did I mishear you?

Kathy Flann: Not really. I find I can only write a story out for a couple of pages if I don’t know something important about the character. I have to go back and rewrite the beginning as a way to discover more about that person. If I don’t know what they do, then I don’t know who they are, and since the plot is what they do, I get stuck. My process is very circular. I go right up to the point where the roadblock is, page six or wherever, and if I’m flummoxed as to what they would do, then, the problem isn’t page six, the problem is page one, and I’m going to go back and figure out what should happen there so I can find out what happens now.

Does it ever happen that you hit the roadblock and then throw something external at the character as a way to push through?

I try to, but it usually doesn’t work. It’s too much me and not enough them.

When did you first know you were a writer?

As a kid, I always wrote, and I always stayed up reading whatever was around the house. My books, but I also read my mom’s books, and I read my stepmother’s books. I read classics like Catcher in the Rye and 1984 but I also read Danielle Steele romance novels, and I think I might have gotten a Stephen King from my stepmother. I’m not sure. I was ten or eleven when I read The Thornbirds in the back seat of the car on a road trip from cover to cover. A lot of scandalous stuff I knew I shouldn’t have been reading. That made it even better.

Can you point to any ‘aha’ moments along your path?

I was an English major in college—that’s always a sign. I did stand-up comedy when I was in college, and when I graduated, thinking it was something I wanted to pursue, I took a job at the Comedy Café in Washington D.C. I was answering phones for them and I thought, great, I’d get to know people, do the open mic night on Thursdays and stuff, but it ended up that the job was really more about answering the phones for the strip club in the basement. All day long I’d get calls from men asking me who was on that night. And I had a little chart on the wall that gave the names of the dancers—“Tonight I have Lola, and Boom-Boom, and Bubbles” and whoever—and they were kind of seedy and gross, these men who called. I found that the comedy world was almost as seedy as the strip club was. It was all men, it was all poop jokes, and the time I would spend at the comedy club was not that pleasant. Ultimately I began to think that I enjoyed writing the material more than I enjoyed delivering the material. Every time I’d get up there, I felt sick. But every time I wrote it, I really enjoyed myself.

I was an English major in college—that’s always a sign. I did stand-up comedy when I was in college, and when I graduated, thinking it was something I wanted to pursue, I took a job at the Comedy Café in Washington D.C. I was answering phones for them and I thought, great, I’d get to know people, do the open mic night on Thursdays and stuff, but it ended up that the job was really more about answering the phones for the strip club in the basement. All day long I’d get calls from men asking me who was on that night. And I had a little chart on the wall that gave the names of the dancers—“Tonight I have Lola, and Boom-Boom, and Bubbles” and whoever—and they were kind of seedy and gross, these men who called. I found that the comedy world was almost as seedy as the strip club was. It was all men, it was all poop jokes, and the time I would spend at the comedy club was not that pleasant. Ultimately I began to think that I enjoyed writing the material more than I enjoyed delivering the material. Every time I’d get up there, I felt sick. But every time I wrote it, I really enjoyed myself.

I realized during that summer that I wanted to go back to school and learn more about writing fiction. Because the material I was trying to do in the comedy world was stories. I wasn’t really telling jokes.

That goes against the grain, especially in a comedy club…

Right. I wasn’t doing at all doing what these other people were doing. I sometimes look back and think maybe I could have stood out if I’d stuck with it and gotten over the nerves.

This part of your past would explain to me why there’s a bone-deep sense of comedy in your fiction.

I think my family is funny. They’ve been through plenty of hard times, but one way of dealing with it is to laugh your way out of it. There’s always a sense with my family that we get each other’s jokes. It remains a shorthand that I have for people I click with—oh, they get my jokes.

Didn’t you start out writing both poetry and fiction?

I did both in my MA at Auburn. I had to petition to do both, and there were faculty fights over whether I could, so one of the earliest lessons I learned in grad school was how dysfunctional academia is. It was very helpful to do the poetry, because when I started as a writer, I don’t think line-by-line prose was a strength. I think I learned that in grad school; it helped me be much more mindful about making better choices. Studying language that closely taught me about economy.

Did you take time out between your MA and MFA?

I took an extra year to do my MA. I did it in three. I wanted to spend an extra year on my thesis, which was [comprised of] two stories and ten poems. My thesis advisors were both journal editors, so at the end of it all, they took me out to dinner, and then one of them said, “We think these stories are really good, so he’s taking one and I’m taking the other.”

I was just happy that I’d turned it in and had learned so much. I’d never imagined that anything I’d done was good enough for that. It was one of the best nights of my life.

And those ten poems?

[Laughter.] They’re still in submission. But those same two stories later allowed me to switch from a PhD program in Rhetoric and Composition at UNC – Greensboro to their fiction MFA. I took three years there too. I feel like I kind of bumbled my way through those six years, but it was a good time.

And then when you were done, you went to teach in Illinois and then on to England, at the University of Cumbria, and then to—

I’ve never taken any breaks. That’s something I feel self-conscious about sometimes. I wonder what kind of writer I would be if I hadn’t been institutionalized since I was twenty-three. I felt I had a lot of momentum coming out of grad school, but it wasn’t until after my fourth year in England—where I was teaching five or six classes, directing both the undergraduate and the MA writing programs, recruiting students, developing budgets—that I got a sabbatical and was able to finish the collection of short stories that grad school had started. At the time I wasn’t even sure I could still write. But I did do the work and it was fun, and I felt I’d found it again.

This would have been—

2005. In the meantime, the English university system was in such turmoil; every year I worried that the department would close and I’d be laid off. I knew I needed to jump before I got pushed.

Why do you think you weren’t able to find the balance?

Why do you think you weren’t able to find the balance?

I was so grateful to have a job that I didn’t feel entitled to complain. I’ve learned over time how to protect myself—I didn’t know to do that then. I didn’t know until I got over there that I was going to be in charge of the two programs. My response was, “Oh, well, thank you.” [Laughter.] But I was just killing myself. Eat and sleep and work twenty-four hours a day, and that was it—summers too.

You come from a hard-working family.

It’s the Midwestern work ethic. Just kind of keep quiet and get it done.

And be grateful you have a job.

Exactly. So I began looking again in America. I figured there would be fewer people with program directing experience than teaching experience, so my strategy was to focus on program jobs. So I ended up getting a job at Eastern Kentucky University, hired to teach three-three and launch a new MFA program from scratch. It was two full-time jobs, down from three. I loved teaching; my students were from modest means and were so grateful, but personally, it was a lonely time. I was able to write, though I wasn’t super-productive. And then Smoky Ordinary got taken, so that was my ticket to go back on the market.

To be near family, I was only applying for jobs in the D.C. area. Two months later there was a job advertised at Goucher, and I applied, and suddenly Madison Smartt Bell is on the phone, and I was literally star-struck. I’ll never forget I said, “I can’t believe you’re on my phone right now!” In the manner of a fan girl. He was very gracious, I have to say.

So many of your characters in Get a Grip are in pain. Starting with the first story, “Neuropathy.”

Oh—you mean physical pain?

Maybe it takes an outside reader to notice.

I don’t know if I did realize that.

There’s this line, “Pain tells him he’s awake to his life.” It resonates outward through the entire collection.

I don’t know when I first became interested in that idea. I’m just thinking through it right now. As a kid, I recall something I read about Native Americans, about how you might inflict physical pain on yourself to try to broaden your understanding. As a teenager going to punk rock shows, I knew kids who would cut themselves out of depression. It was a way of relieving some internal pain that they had. I was interested in how the body could release some internal pain of the mind. One could relieve the other. Physical pain is going to happen to everyone at some stage in his or her life. What is not inevitable, what you do have control over, is your mental state. I guess we’re meeting the characters in Get a Grip at a time when they are trying to re-align themselves, re-align their interiors.

How did this collection become a collection?

I had some stories when I got to Baltimore but they weren’t necessarily finished. The longer I lived here, the more I loved it and realized this was the setting I’d been searching for. Baltimore is the urban version of Smoky Ordinary: odd and funny and quirky. In thinking of a collection, I changed some settings in previously published stories to a suburb or a different Baltimore neighborhood. I had one magic realist story in there about a woman dating a disembodied head—

“Somebody for Everybody?” I love that story.

Yes. I got rejected all over the place for that floating head. I kept getting the comment, “What is this story doing in here?” Eventually I sighed and just took it out. The book was named a finalist for the George Garrett Award the week after I began re-submitting. I still feel kind of bummed out about it.

You can put it in the director’s cut. How did you order the stories? Was it intuitive?

It was difficult because I love my second-person stories the best. When editors reject them, they do so very strongly. “Never send us a second-person story, ever ever again.” So I knew it was a bit of a risk to start Get a Grip with a second-person story, especially because an editor might not even get to a second story. But ultimately I thought at least they’re going to remember this book, for better or for worse.

I feel that some of my strongest work is in the second-person. So I started with “Neuropathy,” then “Half a Brother,” which is in first-, then the third-person “Little Big Show.” A first- and a third-person to show the range, then the title story, which is in second-person. That was the thinking for the first four. After that it was more thematic.

Somehow you manage to make second-person feel like first-person.

I feel that the second-person is close to first-person, at least how I use it. I think that when you’re mad at yourself, you talk to yourself in the second-person: “Oh, you dum-dum, why did you do that? You’re always late and you don’t do anything right” and that only happens in your head when you’re really upset about something. I have this idea that readers know at some level of their subconscious that the story is written the way that voice sounds in our heads and it will hit some emotional chord. It doesn’t work for every character and every situation. It has to be somebody desperate; I think of it as the self divided against the self. Any point of view has to fit the story you’re telling, but the second-person highlights this kind of character. Sometimes I’ll switch a story into second-person when I get stuck, because there is this imperative call for the character in this state to do something. It creates plot, and when I’ve moved past the roadblock, I’ll return to the original point of view.

Do you think you would ever attempt a longer form with the “Flann second?”

It’s an interesting idea, but I think the second-person works best when it’s short. No one ever says, “I hate the first-person.” An editor is never going to forbid any point of view except the second.

I had one story in Let Me See It that was second-person. My editor’s only suggestion was that I change it to first or third.

I had one story in Let Me See It that was second-person. My editor’s only suggestion was that I change it to first or third.

I have students for whom it doesn’t matter how good the story is, they are distracted by the second-person. They take it literally and say “I resisted it all the way through. I am not that ‘you’ person.”

For me, Get a Grip has your generous heart, gorgeous insights into how people think and behave, and lots of physical injuries. With the exception of one story, the couples don’t get together. And there’s never a complete family.

They don’t get together, because that had been the reality of most of my life as a single person. Life isn’t really that tidy.

Some writer once told me good short stories are always sad.

That’s probably true.

I feel that the one story of yours that ends “happily” in Get a Grip is all the more satisfying for its sense of fragility.

Yes, but what’s the next day going to be like for them? It’s not as if their problems are solved in “Show of Force”; they go through so much shit through the story to earn that moment of connection. Life is really hard, but it isn’t always hard every minute. And even in moments where it’s really hard, there can be a triumph. I am that person who always has a difficult time with German art films; they can be just as bad as Hollywood movies. Things so monolithically sad hit my bullshit meter. What interests me as a writer is trying to figure out how to tell the truth about what’s hard and also about what’s happy.

You and Howard have been married now for sixteen months. Has marriage changed your writing?

It has, and it probably will in ways that I’ll figure out in a couple of years. I lived alone for fifteen years. Being in a relationship that is committed, so much of your time is spent trying not to be an asshole. When you’re single, you go out, you see your friends, you’re nice to them, and you come home thinking, “I’m a really good friend.” But now I think, “Oh, wow, I’m really hammering Howard about that.”

It’s probably better that you didn’t meet each other in your twenties.

Absolutely. You’ve been humbled, you’ve been hurt; ideally you’ve gained empathy over time.

Last question: desert island books?

A Good Man is Hard to Find. One Hundred Years of Solitude. Something by Lewis Nordan.

I’ve never heard of him.

He was a magical realist novelist from the South who didn’t get enough attention when he was alive.

I feel like we could go on for another two hours.

Time sure flies when you’re talking about yourself. [Laughter.]