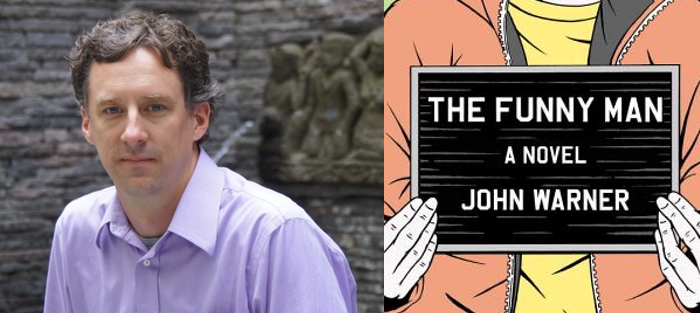

John Warner will still occasionally bring up, ruefully, the sting of receiving a B from me in his first creative writing class, back in the early 90s. I don’t know what I was thinking! I always hasten to remind him that I did give him an A in the second class he took with me. Thank goodness—that A gives me some credibility to claim that I could see the beginnings of John’s unusual and adventurous career as a writer, editor, and literary innovator on the web.

His first publications were books of humor, My First Presidentiary (2001), an inside look at George W. Bush’s crayon-drawn scrapbook, and Fondling Your Muse (2005), a wickedly funny send-up of literary craft books. At the same time John was creating a name for himself as the editor of McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, and the co-founder of (and regular commentator for) The Morning News’ Tournament of Books, an annual and wildly popular sixteen-bracket book competition. He also invented a kind of alter ego for himself: the Biblioracle, possessed of seemingly mystical book recommendation powers. John has recently added to his long list of web accomplishments a column, “Just Visiting,” that he writes for Inside Higher Ed about his experiences as a non-tenure track university professor. He teaches at the College of Charleston.

In 2011 Soho Press published his novel The Funny Man, the unsettling tale of a stand-up comedian whose fame rests on his ability to fit his entire fist in his mouth (John is now working on the screenplay for the movie version). His latest work of fiction is Tough Day for the Army, just out from Louisiana State University Press, a collection of structurally sophisticated and deeply felt short stories that balance empathy and humor with a clear-eyed look at our human foibles. It’s already creating a buzz, with a number of terrific initial reviews, including a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly:

Warner has produced a short story collection that mashes the surreal with the heartfelt to fantastic effect . . . Like George Saunders and Etgar Keret, Warner plays with conventional mores, turning them on their ear. Also like those authors, Warner successfully layers his satire with rich characters and a general playfulness with form that somehow renders a deep emotional resonance. The result is a well-written and wonderfully comedic collection of short stories that gooses as much as it gives.

This interviewed was conducted in two parts. In the first, we discussed John Warner’s story collection, Tough Day for the Army, and in the second his career as a kind of Internet literary impresario. You can find the first part of the interview here.

Interview:

Philip Graham: You’ve been at the cutting edge of the “literary web” for quite some time now: an editor of McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, a co-color-commentator of The Morning News’ Annual Tournament of Books, and you’re also the scarily all-knowing Biblioracle. Was this a Master Plan, or did one cool thing just develop after another?

John Warner: I seem to be congenitally incapable of making plans. This is often to my benefit, in that I find myself open when opportunities arrive—like taking over the editing of McSweeney’s—but it also has meant an extremely ad hoc career.

Two of the things you mention, the Tournament of Books and the Biblioracle, are both a consequence of saying “yes” to a lunch invitation from my friend Kevin Guilfoile, back when we were strangers—or even, to my mind, enemies. It was the early days of the McSweeney’s website, long before I took over the editing, and he had published something betraying that he worked in Chicago, a place I considered my turf when it came to the McSweeney’s universe. He’d noticed a Windy City reference in something of mine and because he is not a petty little jerk like me, emailed me to grab a burger.

We found ourselves awfully simpatico about a lot of things—music, books, movies—and we started collaborating on pieces for the late, lamented Modern Humorist, which turned into my first book, My First Presidentiary (Three Rivers Press, 2001), which we wrote jointly. Later, when he and Rosecrans Baldwin and Andrew Womack dreamed up the Tournament of Books, Kevin asked me if I wanted to participate. The Biblioracle column for the Chicago Tribune came about because Kevin mentioned what I’d done for The Morning News to the editor.

That “literary web” really is a web of connections, and you never know how the next opportunity is going to make its way to your door. I’ve been tremendously lucky that way by being in proximity to talented people who are willing to put me to use.

Hmmm, you’re making yourself sound a little like the Forest Gump of contemporary literature. I think perhaps all that “being put to use” at just the right time might have been because your sterling inner qualities were readily observable.

Certainly you are one impressive Biblioracle (is that word in the new Scrabble dictionary, by the way?). Readers give you a list of their five most recently read books, and you then offer them a recommendation for their next book to read. You’ve built up a lot of satisfied customers, too. And at The Morning News, you did all those recommendations in real time—I think there was a two-hour stretch of supplicants each time. Very impressive—how did you pull that off?

The live, two-hour Biblioracle was a kind of madness, where I got myself into something without knowing what it was. I had no idea there was such a hunger for people being told what they should read next. Having made a promise to give everyone a recommendation who wanted one, I drove myself to the brink of my sanity in an effort to follow through.

But it was really fun, and maybe instructive as well. It caused me to wrack my brain for anything and everything I’ve ever read. I was marching around my house, looking at my shelves, and digging out notes and syllabi from graduate school, and anything else I could think of. There were so many great books that I’d forgotten ever reading and yet they were obviously lurking there inside me.

One upshot was that when I started The Biblioracle, I was about 70/30 digital books to physical books and I’ve swung to something like 5/95. The only time I read a digital book now is when I just can’t get a physical copy. I realized that to me, the artifact mattered, even if it’s just going to sit on the shelf.

Yes, you seemed like Superman when you were “live.” Now folks e-mail you at the Chicago Tribune, where you’ve housed your literary avatar, and so at least you get a decent amount of reflection time before making a recommendation.

I always wanted to test your abilities, but never managed to work up a request. Though now, since you’re something of a captive audience, I can get my wish! So, here are the last five books I’ve read: Bullfight, by Yasushi Inoue (Pushkin Press, 2013); Horses of God, by Mahi Binebine (Tin House Books, 2013); My Brilliant Friend, by Elena Ferrante (Europa Editions, 2012); The Missing Year of Juan Salvatierra, by Pedro Mairal (New Vessell Press, 2013); and The Empire of Necessity, by Greg Grandin (Metropolitan Books, 2014). To widen the field a little, I’ll (cheat and) add the two books I’m currently reading: How to Live, or A Life of Montaigne, by Sarah Bakewell (Other Press, 2010); and Giovanni’s Room, by James Baldwin (Delta, 1956).

Oy, the pressure! I’ve found that the more I know about the person I’m recommending to, the less accurate my recommendation. I have, by far, the worst batting average with my wife, to the point where she rarely even consults me before choosing what to read anymore.

The extra difficulty here is that you read so widely in world literature, while the world literature I read usually comes from you. In this case, I’m going to recommend a book that I definitely want you to read, but I also want everyone else to read because it’s been an unjustly overlooked first novel—the number of which are legion—that I’m trying to get the word out about in as many for a as possible: A Brave Man Seven Storeys Tall, by Will Chancellor (Harper, 2014). It’s about an Olympic-level water polo player who loses an eye in his last collegiate game and runs off to Berlin to become an artist. Complications ensue.

The extra difficulty here is that you read so widely in world literature, while the world literature I read usually comes from you. In this case, I’m going to recommend a book that I definitely want you to read, but I also want everyone else to read because it’s been an unjustly overlooked first novel—the number of which are legion—that I’m trying to get the word out about in as many for a as possible: A Brave Man Seven Storeys Tall, by Will Chancellor (Harper, 2014). It’s about an Olympic-level water polo player who loses an eye in his last collegiate game and runs off to Berlin to become an artist. Complications ensue.

Man, oh, man, this is why you are called the Biblioracle. I have never ever heard of this book. It’s downloaded now. Unlike you, I’m still engaged with the e-book thang (every one of the books I mentioned in my list I read as an e-book). Though I am reading more paper books these days, maybe 30% of the total. That’ll probably climb, but at my age I have to worry about vanishing shelf space.

The Morning News’ Tournament of Books, for which you are one of the expert commentators, is a big source of book tips for me. It’s a March Madness whose myriad pleasures I look forward to every year. I’d love to hear any gossip or tales out of school about the backstage planning…

Well…I could tell you, but then I’d have to kill you. Truthfully, the planning is somewhat mundane. My role is to read lots and lots of books published in the calendar year and then when the time comes to select the field to weigh in with my thoughts and opinions. It’s a collaborative process, and I never get everything I want because everyone tries to be as conscientious as possible about getting a good mix of titles. That mix is always the hardest part if you’re considering not only things like gender and ethnicity, but also genre, reader interest, indie titles versus commercial publishing, etcetera. Each year we could come up with a list of sixteen totally different books than the ones we’ve chosen that would be just as credible a lineup.

Though, that’s also the point. Prizes or “best” lists are inherently arbitrary. We just make that transparent.

Yes, there are all those judges for the various brackets, a zombie round so readers can have a say in resurrecting favorite books that lost a round, your and Kevin Guilfoile’s commentary on the latest decision by a judge, and then what has come to be known as the “Commentariat”—all the folks online who have their own strong opinions about those sixteen books. The whole enterprise feels like what we’d encounter if the National Book Award were a reality show. There are so many moving parts.

The thing was dreamed up by three guys in a bar writing on a cocktail napkin. I think it’s amazing to everyone involved that we make it through each year without the wheels flying off. It takes a lot of cooperation among the staff at The Morning News and the judges. A single irresponsible tweet or failure by a judge to render a judgment can put a wrench in the works, but this just hasn’t happened. Even the Commentariat, while spirited and irreverent, never seems to become the kind of cesspool one might expect of open discourse on the Internet. I think the fans are as protective of the process as we are.

Sometimes I wonder how you manage to keep so busy, and then I remember that on top of all of this you also teach. Which reminds me that I left out of my first question another of your literary Internet presences: “Just Visiting,” your excellent and thoughtful blog for Inside Higher Ed, in which (this is the short version) you describe life from the non-tenured teaching side of academia. A large number of writers, young and not so young, fill these overworked positions while trying to fulfill their literary ambitions. There’s a good discussion going on now for your latest entry, “We Could All Use a Little Tenure.”

This is another good example of the literary web or kismet or whatever you want to call it at work. I started writing for Inside Higher Ed because our mutual friend, John Griswold, was transitioning to a new job and he asked me to fill in for him. I had no idea if I could do it, but I figured I’d give it a try and have found it very engaging and enjoyable. I also get paid, which is nice, and sometimes rare in this day and age.

I feel like a cautionary tale to others like me, people with MFA’s who write and like teaching. In a lot of ways, I’m a success story. I’ve been employed for fourteen straight academic years, I’ve never left a job except under my own volition, and I have health insurance. On the other hand, I did the math on “lost” salary for the six years I worked at Clemson where I made 25k a year teaching four classes a semester. I published two books there. I got a grant to help start a student-run publication. I advised theses for both graduates and undergraduates. As an assistant professor I would’ve started at 60 – 65k. That’s over $200,000 difference in salary during that period.

It’s a crummy system. I don’t really recommend entering into it, except that I also very much enjoy my work, and can’t imagine doing anything else.

Well, seeing that you are something of a “digi-lit” hero, your candor on the downside of your career is something I admire. It reminds me of an amazing piece you wrote that was an utterly crazy idea that could have gone horribly wrong: you contacted the fellow who gave your first novel, The Funny Man, its worst review (for the record, I love that novel, and it has done quite well, too—a paperback edition, plus you’ve been tapped to work on the screenplay for a movie version). The interview with that reviewer worked because you weren’t out for revenge, you were fueled by curiosity: you wanted to have a conversation with someone who had a very different take than you did on your novel—what might you have done with the book that could have won him over? I think most writers imagine conversations with reviewers of their books, but no one has had the nerve to give it a try, and in print! You are some brave dude.

Well, seeing that you are something of a “digi-lit” hero, your candor on the downside of your career is something I admire. It reminds me of an amazing piece you wrote that was an utterly crazy idea that could have gone horribly wrong: you contacted the fellow who gave your first novel, The Funny Man, its worst review (for the record, I love that novel, and it has done quite well, too—a paperback edition, plus you’ve been tapped to work on the screenplay for a movie version). The interview with that reviewer worked because you weren’t out for revenge, you were fueled by curiosity: you wanted to have a conversation with someone who had a very different take than you did on your novel—what might you have done with the book that could have won him over? I think most writers imagine conversations with reviewers of their books, but no one has had the nerve to give it a try, and in print! You are some brave dude.

I think it might be different if I thought someone was going after me as opposed to the book, which can and does happen, particularly on social media, and sadly effects women far more than it does men.

The review itself was so venomous that it didn’t sting all that badly. I know when I don’t care for a book, it isn’t personal, and it also doesn’t mean the book is necessarily worthless. Books are like relationships for me. It was clear that the reviewer and my book were two ships passing in the night. One person’s pleasure is another person’s poison, and that usually says more about the person than the book.

That approach certainly insured that the discussion between the two of you was so touchingly civilized. As you mentioned wonderingly in the first part of our interview, sometimes humans, unpromising clay that we are, can be “genuinely good and kind.”

Part of me felt like I owed the reviewer an apology for disappointing him so thoroughly, but at the same time, my ego told me I had nothing to apologize for. I just couldn’t resist trying to find out where I’d gone so “wrong.”

As you say, I was mostly just curious, and in the end, it’s a privilege to publish a book at all, even one someone hates. I hope someday to create something that’s so widely read that it gets 100’s (or even 1000’s) of 1-star Amazon reviews.

Editor’s Note: Read Part I of Philip Graham’s interview with John Warner.