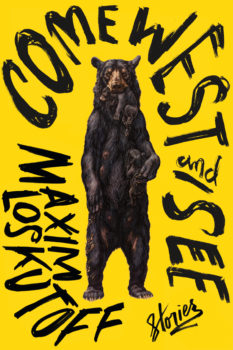

America is a nation full of people who don’t feel like they belong to a nation. Maxim Loskutoff’s debut short story collection, Come West and See (W.W. Norton), explores precisely this phenomenon. Nestled in a pocket of the country largely ignored by the cultural powerhouses on the coasts, the people of the interior northwest have plenty of reasons to feel separated from the experiment called America. Spanning from eastern Oregon, through Idaho and Montana and Wyoming, it is a mostly isolated landscape by turns desolate and verdant. It is a place where those who seek to get lost will find their wish fulfilled, and those who seek to get found might wind up lost anyway.

Through Loskutoff’s eyes and pen, this physical landscape is brought to life in human form. The collection—stories from which appeared in The Southern Review, Ploughshares, Narrative, and elsewhere—is set almost entirely in the interior northwest, and it casts light on individuals struggling to find a place for themselves in America. More poignantly, they find themselves struggling to fill the niches in their own emotional lives that they have attempted to carve out for themselves, only to find those niches closing upon them by circumstance or their own stubborn adherence to an identity they though would hold them fast.

There is a palpable sense, throughout Come West and See, of self-exile. This can come about through geography, due to the isolation of its primary setting. But more significantly, many of Loskutoff’s characters are marked by a self-inflicted psychological exile as well. It pervades the lives of characters like Russel in “Umpqua,” who crashes his car into a tree after a fight with his girlfriend at a hot spring. And Lila in “Daddy Swore an Oath,” who ponders what life might have been had she married another man while she waits to see if her husband will survive a standoff against the federal government. And Les in “Too Much Love,” who joins a militia group because he doesn’t know what else to do with his life. It affects uprooted people elsewhere in the country too, like the female protagonist of “Ways to Kill a Tree,” stranded in Colorado, who pats her purse to make sure she hasn’t stolen anything from a library.

Loskutoff brings these estranged characters vibrancy by forcing them into situations of emotional life and death in which they must decide how they will live. (Physical life and death is rarer, though it lives in the background throughout and comes to the fore in later stories.) Often, this psychological extremis overlaps with the feeling of disassociation from nation and culture. The strongest characters in this book are the ones who are most adrift, most ready to latch onto whatever comes next, and this makes them both tragic and dangerous. They have a keen sense of their own separation from an America that is leaving them behind. Lila from “Daddy Swore and Oath” sees her husband as “fighting a world that had changed out underneath him.” Russell from “Umpqua” sees:

The whole country pressed in on the dark trees around me—Portland and Seattle, self-driving cars, smart watches, robots—trying to push me out. Like I wasn’t good enough to be here anymore. Like I was something to be ashamed of, as if we hadn’t built it in the first place.

Loskutoff’s characters are primarily isolatoes, to borrow a phrase from Melville, and their separation from themselves and each other drives tales of emotional survival and desolation. In addition, the stories that take place in the interior northwest unfold before a significant sociopolitical backdrop that must not be ignored. The characters make frequent reference to “the Redoubt,” a phrase that refers to the rural separatist movement declared by James Wesley Rawles in 2011. Rawles, blogger and author of survivalist novels such as Patriots: A Novel of Survival in the Coming Collapse, proposes the interior northwest as an “American Redoubt” where patriots can live free or die in defense of their principles—which are predominantly libertarian and fundamentalist Christian.

Given recent seismic shifts in American politics—with so many Americans who felt isolated from urban and coastal culture having their say at the ballot box—this is a rich, dynamic setting for contemporary fiction. Loskutoff handles his backdrop without sensationalism, and he eases us into it. In the earliest stories, we can see references to militia/government skirmishes as echoes of recent American political situations. The conflict that makes Lila worry about losing her husband, for instance, is reminiscent of the 2016 seizure and occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, carried out by armed militants who share many of the same political goals as John Wesley Rawles. But as we travel deeper into Come West and See, we come to understand that these ongoing skirmishes are an everyday reality for its characters. The last three stories pull us into a battle-ready Redoubt where this struggle with the feds is in full swing—and even into spots where it appears already lost.

By the end of the collection, the delicately balanced emotional landscape of the interior northwest has given way to a spiritual wasteland, reminiscent of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and even more so Octavia E. Butler’s The Parable of the Sower. People have given up on maintaining their dignity and have resigned themselves to their own cruelties, fighting for survival and the self during a de facto civil war. We realize that Loskutoff has slipped us into an alternative future America in which the federal government is dropping bombs on citizens who eagerly engage in battle against it.

By the end of the collection, the delicately balanced emotional landscape of the interior northwest has given way to a spiritual wasteland, reminiscent of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and even more so Octavia E. Butler’s The Parable of the Sower. People have given up on maintaining their dignity and have resigned themselves to their own cruelties, fighting for survival and the self during a de facto civil war. We realize that Loskutoff has slipped us into an alternative future America in which the federal government is dropping bombs on citizens who eagerly engage in battle against it.

The edge-of-your-seat final story in the collection, “The Redoubt,” features a couple who have abandoned the separatist movement for “lawful states” and paid a price for it: arrows stuck in their flesh that will kill them in due time. The Redoubt did not offer them the freedom they had hoped for. The story’s narrator sees it as “the true West, where all the Indians were dead and we white men had finally gotten around to killing ourselves.” Come West and See offers two ways to understand that line: groups of white men killing each other, and each man killing himself—slowly but surely—by holding onto his chimeras, punishing himself for real and imagined wrongs, and burning bridges between himself and others.

With such a heavy backdrop, it would be tempting to become politically strident and grandstand. Loskutoff avoids this trap, hewing to the emotional lives of his characters as their lives are profoundly shaped by the politics around them. In this sense, Come West and See is a literary response to the separatist movement: a calm-eyed look at people who feel cornered by America’s present and not invited to participate in its future.

And though the collection is an unsettling one, it never achieves that tone cheaply. Loskutoff could easily have played his interior northwest characters for shock value, showing them in a condescending light. But to his credit, he doesn’t take the easy way out. He has an eye for how landscapes shape people and how people shape themselves through the decisions they make and unmake. The characters of Come West and See possess an urgency that gives them weight and consequence, even if most of them are adrift. If there is a great novel to be written about the life of the 21st century interior northwest, then Maxim Loskutoff is a prime candidate to author it.