On June 20, four writer-readers chatted via Skype about Richard Price’s novel Lush Life and The Wire. Participants included: two poets — Britta Ameel (BA) and Charlotte Boulay (CB) – and two fiction writers — Michael Shilling (MS) and Elizabeth Ames Staudt (ES).

On June 20, four writer-readers chatted via Skype about Richard Price’s novel Lush Life and The Wire. Participants included: two poets — Britta Ameel (BA) and Charlotte Boulay (CB) – and two fiction writers — Michael Shilling (MS) and Elizabeth Ames Staudt (ES).

—-

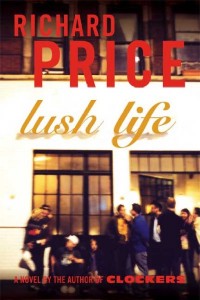

SUMMARY: Richard Price’s Lush Life transcends the police procedural / urban crime novel with layers of social commentary and a cast of memorable characters. The author of Clockers and writer for HBO’s The Wire paints New York’s “new” Lower East Side in shades both gentrified and gritty; here is a maelstrom of cops, losers, and dreamers–all going for the big score, all searching for redemption. A group of young men is bar-hopping when Ike, a young white bartender, is fatally shot. Failed actor-writer-restauranteur Eric Cash tells detectives the man’s death was the result of a stick-up gone wrong, a random mugging by teens from the projects. But some witnesses disagree. Lush Life explores the tragedy’s aftermath, following NYPD investigators, Eric, Ike’s father, and alleged shooters Tristan and Little Dap.

—-

I.

MS: It’s a pleasure to be here, and I hope people reading our discussion will respond with their thoughts.

BA: Big caveat: I still have some pages to go in Lush Life. But I’d love to talk about it …and don’t hold back on how it ends.

ES: I think you will know how it ends without reading the end.

BA: Really? I’m kind of dumb when it comes to mysteries.

ES: But it’s not a typical mystery, right?

CB: The key is, the end is not a mystery.

BA: Well, no, but I mean–it’s kind of a whodunit, right?

ES: Something insightful not by me:

“Price seemed to intuit that the relative unimportance of ‘mystery’ to the police procedural—which often makes no effort to conceal from the reader the identity of the killer—offered the perfect vehicle for his Stoic moral vision of the vanity and ruin of human ambition.”

That’s on Clockers and it’s from a review by Michael Chabon (of Lush Life, in the New York Review of Books).

BA: Right–it’s not really a “mystery” as such…

MS: No, it really felt more like a police procedural/life will crunch you into little bits-drama than a whodunit.

ES: I like that, Michael. “Life will crunch you into bits”—a new genre?

CB: I decided not to read that review by Chabon, because I was afraid it would bias me. But now I see the stoicism throughout. I’ve never liked stoicism; I like to whine too much.

MS: I always get my stoicism and solipsism mixed up.

II.

MS: Which characters did people respond to?

BA: I loved Yolanda.

ES: Interesting. Michael, you thought she was extraneous, no?

MS: Yolanda was frustrating because she existed only in dialogue.

BA: I liked Yolanda, I guess, (and here’s another conversation entirely) because she reminded me so much of Kima on The Wire. Matty—I wanted to like him, but what was up with his blasé attitude toward his family? And his weird thing with sex with that woman in the No Name?

MS: Yeah, but with Matty those were idiosyncrasies I wish Price had built on.

CB: I loved Yolanda too, mostly because I could imagine bits of her life and the ways it made her actually compassionate at times, but then some scenes turned into a “gotcha!” because I never knew which details she was inventing. She’s a great character in the way she blends fiction & reality.

BA: Yeah, she was not in the picture—it was strange when I got to a part that mentioned her husband and children (I think she rented Netflix for her kids). I liked Yolanda because she seemed aware of how she could manipulate people—but Price didn’t do much with it dramatically because, aside from dialogue, he didn’t give her much space.

MS: The Kima comparison is apt, but I love Kima so much it hurt Yolonda.

ES: But Yolonda becomes more significant with the book’s final scene.

CB: You mean the penultimate chapter, before the epilogue?

ES: Yes, that’s the one. I finished the book pretty recently and I’d totally forgotten that Matty even had that moment in the final chapter of deciding to rail on his son face-to-face, still referring to him as “the other one.”

MS: OK, what I wanted more from the book was a sense of the characters relating; they are too, uh, existential?

CB: Hmm. I would have called the characters whatever the opposite of existential is.

BA: I agree, Charlotte. We sort of got it from Matty and all his interactions with various people in the office and on the street… But there was so much going on at any given time, that I think it seemed like we didn’t have a grounding point, a point in time where all characters were defined enough so that we had a full feeling/understanding of them…

CB: I felt like the characters couldn’t really relate to each other because they were all so traumatized by life, beaten down by it, for the most part. Especially that poor schmuck who lived at the police station.

MS: Billy Marcus? He also didn’t have enough set-up for the reader for him to lose his shit so fast. But he’s an interesting character.

BA: So–maybe Price is a dialogue master but not an interaction master.

MS: Sounds accurate.

ES: Interesting distinction, but I don’t know, maybe people aren’t interaction masters.

CB: I agree about Billy. I wanted to slap him most of the time. I couldn’t understand until late in the book why Matty was so nice to him.

BA: Yeah, I wanted to slap Marcus so many times. I never had a clear picture of him except as a babbling baby. Sure, he lost his son, but it was hard to feel sympathy for him when we really never knew who HE was before Ike entered the story. Matty just feels sorry for him…? Why is he so worried? Family similarities?

MS: I think Billy is an example of how you can make a character realistic but not interesting.

CB: But also, maybe that’s the point—that identity-less victims & their families constantly enter Matty’s life, and he has to deal.

ES: Wow, I felt really differently about Billy; to me, his grief was believably overwhelming. I appreciate your point, Charlotte. That idea of the victims being identity-less emerges again in that penultimate chapter—where Matty essentially admits to feeling less sympathy for the victims that don’t look like (his also sort of identity-less) sons.

III.

MS: It’s hard to tell in a book like this where the intention is. Maybe that means Price is genius.

CB: I’m not sure if I understand how you’re thinking about “intention”?

BA: Michael, that makes me wonder about genre… I felt like I was reading at once literary fiction and police drama… but I suppose that’s a distinction that doesn’t really matter. I guess I’ve just not read a lot of fiction like this—I’ve mostly watched it.

MS: I only meant that sometimes the writing is so punchy and loose, as is the dialogue, that I don’t know how hard Price was working . . . I’m not explaining well.

It definitely transcends genre . . . but then again I hate genre-haters.

BA: That’s funny because I was so impressed by the writing—I guess because it’s something that appears so easy but in truth, is so hard. In fact—I always watched The Wire with the subtitles on so I could fully “get” it. And I had to reread a lot of the dialogue sections in the book—maybe that says more about me than Price…

MS: What about Eric?

ES: I felt I was missing something in my attempts to connect to him.

It’s odd, because he should, in many ways, be the easiest to connect with (dealing with failed ambitions, being directionless and a total dilettante).

BA: Eric really bothered me, but I feel guilty saying that—like I feel sorry for him enough that I can’t dislike him… But that pity for him makes me wonder how well-developed he was. I did “connect” with him on that level—working in a restaurant, trying to be a writer, etc. But—and I guess this plays into what we’re all saying about him being the most fleshed-out—I still didn’t feel like there was much on his soul level that I wanted to connect with. Perhaps, again, that says more about me and my own insecurities than anything else. I suppose it’s a good thing — that Price has me worked up over a character who isn’t likable.

CB: I felt genuinely bad for Eric for most of the book, even when he was treating women badly, but I didn’t ever like him. He was an interesting example of an unlikable person I felt sympathy for. I can’t think of many characters like that. Maybe some John Irving heroes.

MS: I thought he was the most fully developed character. He had an internal life that was believable, especially after he meets Bree. It felt like Price took the time to evolve him from a garden-variety fool to a tragic figure.

CB: Except, it’s hard to call it “tragedy” on that scale. Eric is the only one worried about himself in the whole book. He’s so self-absorbed that it’s difficult to feel that the outcome is tragic.

BA: You don’t think Tristan’s worried about himself? Or Steven? I guess we don’t see him that much.

CB: Steven’s even more self-absorbed than Eric, actually. They’re both hard to like. But it’s an example of how self-absorption can be manifested in two opposite directions — one inward, one outward. (Yet they’re both actors, which is interesting to consider.) There’s a parallel to the end, when Yolanda says, “So his friends suck, huh?”

MS: Of course I never need to like a character; I just want to feel their desire for something and have them not be a sociopath.

CB: That’s interesting. I do need to like characters. I mean, I don’t have to, but if I don’t the reading experience seems a little empty.

BA: I agree. Not that I need to be friends with a character, but I need to see something in them that’s likable… something that I can hold on to.

MS: All I need is a believable idiosyncrasy; if the actual writing is great, that can be enough. Tristan just didn’t get enough ink for me to have much of a feeling about him.

ES: That raises an interesting parallel, Britta. Tristan’s definitely worried for himself, and both he and Eric are desperate to be heard and recognized—to have some power.

CB: Yes. That’s definitely a bug theme here. Who has power & who doesn’t.

A big theme, that is.

ES: No, it is a bug theme! Because that was the big moment when it felt to me that we should feel most sympathetic for Eric—when he finally confronted Yolonda about making him feel like a “bug.” The squashed-to-bits-by-life genre.

BA: I think that’s why I like Tristan more than Eric – even considering how small a role, on the page, Tristan has. I saw something in him that was more honest, more raw, less jaded. Something I could appreciate more.

CB: Actually I loved Tristan & felt worse for him than anyone.

ES: I also cared for Tristan. And Charlotte, your bug parallel (even if accidental) did make me think about Eric and Tristan both wanting some power, and how they’re both invisible to so many of the people around them (particularly those charged with caring for them).

CB: What do you all think will become of Eric?

ES: He has a happy ending, right? In the house on the boardwalk with the seven-dwarves tattoo-woman?

MS: I think he’s someone who will always be blown sideways through life.

CB: Does anyone think he’s learned anything from this experience?

MS: I do, but I think his heart is so calloused that he can only change so much. We all know people like that.

BA: So how does he change? Or will he change?

CB: Yeah. Calloused. I think the changes in Eric are there, but they’re easily masked by the continuing lack of control he has over his bad choices.

MS: Like Steven.

CB: In the end, Eric is still not doing the job he really wants to do, not acting, making some kind of connection with a woman with a seven dwarves tattoo who the police officer—right?—and Ike have also slept with…I’m not making a moral comment, I’m just saying, she pops up all over the novel and not in the “I signal a stable relationship” kind of way, you know?

ES: Steven was fascinating; I’m so interested in the way people’s brushes with death/nearness to tragedy are exploited, particularly by those who don’t seem to be feeling a whole lot of actual grief. That spectacle of a memorial was a really amazing scene.

CB: It was–and the looong paragraph describing the majorette guy? That was pretty great.

MS: Yes, that scene was more tactile than the others, I feel like Price let it happen in a good way.

CB: I think my notion of whether Eric will change may say more about my own biases than about the hint of a possibility of redemption in the novel. And that’s something I’m really interested in here: redemption.

BA: Right, I agree. Redemption. Are you interested in the characters’ redemption, redemption in general, your redemption as a reader?

CB: All, I guess. And maybe we can segue to The Wire next.

IV.

ES: Certainly a fair transition to The Wire, then, too—can anyone ever be redeemed if “the game is rigged”?

BA: No. I think that’s the whole point. But MY GOD that is depressing. And how can we possibly be interested in something so depressing as to not even have the possibility of an ounce of hope?

CB: I think because we’re acutely aware of our own privilege.

BA: What I mean is–why are we so drawn to something that’s so dark at the end of the tunnel?

ES: There’s hope in the end for some, though, right? Both The Wire and Lush Life conclude with a hope that seems really rooted in place (both location-wise and socioeconomic-wise).

CB: In other words: the privilege of, more or less, playing outside of the rigged game, or being part of the community that makes the rules.

BA: So what do we do in our community of privilege? To make redemption possible for all of us?

MS: That goes to the heart of this type of story, I think. Are people who have the luxury of enjoying a story about people with no way out really able to get the point of the story? Oh shit, what am I talking about? Help me sort this out.

BA: No, no, absolutely, Michael. What do we get out of a story like this? Are we merely voyeurs? The closest I’ve been to this kind of story is today in the courthouse paying for traffic school. And is Price a voyeur?

CB: Well, not to switch topics again, but I’ll just say that there are also big themes of masculinity here, and I wanted to tell Eric (& certainly Steven, & to some extent Matty, although his PTSD excuses him a bit) to fucking grow up as men, and that they also participate on the privileged side, although we see a bit of how Matty is fenced in by bureaucracy, but otherwise they just make shitty choices.

BA: I said that out loud more than once. Grow up. I think that’s why I’ve been innately more interested in the youngsters in both Lush Life and The Wire—because they are in the moment of growing up and have the potential to learn what it takes to be an adult, a mature man who doesn’t need to flaunt his masculinity.

CB: And yes, I think Price is a voyeur, and that’s part of the pleasure of the novel, but it’s also part of the pain because once we care at all about the characters, we can’t look away. And we should look at these hard things and feel guilty about them, — but not so guilty that it paralyzes us. I don’t know. This is where I get bogged down in my own conscience.

ES: Conscience, guilt, etc: I always say that I credit fiction with making me an empathetic person, and then, when wrestling with how to translate that empathy into any kind of positive/actual change, I give myself what I sometimes consider to be an “out” like, Oh, I’ll try to write books that (ideally, hopefully, ultimately) would continue that empathy-generating. On bad days I worry this is just me adding to a circle-jerk (to take up the transition to masculinity).

CB: That is so right on.

MS: I think you are being too hard on yourself.

ES: Maybe, but it’s worth thinking about, right? David Simon is very outspoken about wanting people to do more than just marvel at how fucked up things are…I think he really does believe The Wire could create change.

MS: It’s funny — to me, a voyeur is someone who takes pleasure in the adversity of those being viewed, and I don’t think Price does.

CB: Is he a fly on the wall, then? There’s a difference between looking and gawking, and at times I think this novel flirts with that line, as does The Wire.

BA: It feels more like Price is just handing us the story. But he sure does take pleasure in his writing. When do you feel like it’s gawking, Charlotte?

ES: The difference seems to be between just looking/gawking and totally immersing. Both Price and Simon are obsessive researchers, right?

BA: When do you feel like it’s gawking, C? I never got the sense that Price was a gawker. I fully believe he’s experience what he’s telling us, to some degree. I fully trust him.

CB: Well, I can see Matty backing away from that line several times, like when he retreats from Billy in the hotel room, or Eric on the balcony burning his script. But Tristan in pain with the hamsters? How can we not see it, but also, how can we?

MS: He seems to be very honest and, again, not sentimentalizing the environment.

BA: You’re right, Charlotte. But then again, sometimes these scenes feel exaggerated, which makes me question how much I “believe” Price.

CB: So, maybe this brings up race in the novel as a segue to The Wire. Does it matter that Price is white? That the creators/major writers for The Wire are as well? I always wonder about this when I’m watching it.

MS: I honestly don’t know; I need to think about it.

BA: I think it does matter, but every time it crosses my mind, I back away from it because I’m too nervous… There, I said it. I’m nervous about the race conversation. But it remains a huge elephant in the room with regards to both the novel and the show. Or rather, with we (four white writers) as “watchers” of the book and the show.

MS: I mean yes, it matters, but maybe in the same way that it matters that a vegetarian can write about a meat eater. There’s something secondary to shared experience of human suffering that all that all who are not dead inside can share. But it’s still essential.

CB: In interviews, so many of the black actors say things along the lines of, “I’m so thrilled to be participating in this story of my hometown; it’s so true to life, I knew these people….etc.” But how do Simon…and Price have the balls? Is this a false lead? I think maybe. I don’t question anymore when men write wonderful women characters, so maybe it’s all just a triumph of the imagination.

MS: I’m an optimist that humans, regardless of backgrounds, all have the same core set of desires, which are then personalized and made unique in billions of ways (Not explaining away the complexity, by the way).

BA: Charlotte, are you worried that Simon and Price are getting too much credit for giving voice to this kind of story?

CB: No, I don’t think so. I just try to imagine myself writing about characters whose rules in life and experiences are foreign to my own and can’t imagine I could pull it off. But then, Simon & Price have lived these lives, to some extent.

BA: I’m on the same page; I don’t feel like I could pull it off.

CB: But, you & I, hello? Poets? I don’t write dramatic monologues and neither do you? (Thank goodness). Let’s leave this one to the fictionistas.

MS: But you guys get to be the priests of the invisible. JEALOUS.

BA: Ohhh, I like that. Priests of the invisible.

MS: That’s Wallace Stevens, not me.

BA Ah yes, Stevens. I wonder if he could have written a police noir drama.

CB: Would you recommend Lush Life to people who love The Wire? Or not?

BA: I would. It took me awhile to get into it (like The Wire), but I was totally taken in by the dialogue and the Wire-ness.

MS: Yes, it’s very similar but without the, uh, genius.

ES: For Wire-withdrawal, I’d recommend Clockers (with the genius). Clockers, like The Wire, just had more of those moments where you (paraphrasing Zadie Smith paraphrasing Iris Murdoch) “realize the realness of other human beings”—not just in theory but in an acute, painful, extraordinary way. What we want from fiction, yes?

BA: So, Charlotte, Lush Lifewasn’t like this (the acute understanding of another human) for you?

CB: In a lot of ways it was. But somehow it’s not as powerful as The Wire, and I’m not sure why.

BA: I agree—does it move too fast?

CB: It can’t be the medium, because I feel strongly that many, many texts outweigh screen in their complexity & pathos, but not this one. Yeah, maybe pacing is part of it. Lush Life has a little less humor, too, and the characters are less well drawn in some way. Funny, I disagreed with Michael at the beginning of this conversation, but maybe I’m coming around to that realization.

MS: I think that’s the first time I ever changed Charlotte’s mind.

[Michael signs off, triumphantly]

V.

CB: Should we end with a chat about the title? I really love it; I think it’s great. Because…hmm.

ES: Because you love alliteration above all else?

CB: Because “Lush” is jungly and all-encompassing but also tangled and alcoholic and crazy at the same time. And yes, I love alliteration a lot.

ES Such a lovely assessment. Only a priest of the invisible could do that (read the title in that way).

BA: I was never sure what to make of the title. Does it refer to one character’s life in particular, do you think?

ES: No. To me it feels decidedly “big”—like the book. About everyone, everything, trying to drink in everything in the whole world. Which Price does better than most.

BA: Right–Price writes about life—the bigness of it, the lushness (positive and negative) of it…and better than most—he is uncannily good at encompassing like three million situations in one scene. But I’m always so skeptical of the word “life” in titles.

CB: You know, you couldn’t say, “I don’t want my life to be lush,” right? But if it was, that might not be all good things. My favorite title will always be “Pity the Bathtub its Forced Embrace of the Human Form,” [Matthea Harvey’s first book of poems]. So really Lush Life doesn’t even come close.

BA: Yes, nothing could come close.

ANNE: Had to insert here (I’m just reading this later, wearing my Editor Hat, and I haven’t even read the book!) that “Lush Life” (Billy Strayhorn) is also one of my favorite standards; the 1963 recording by Johnny Hartman and John Coltrane is gorgeous and sad. Here are the lyrics:

I used to visit all the very gay places

Those come what may places

Where one relaxes on the axis of the wheel of life

To get the feel of life…

From jazz and cocktails.The girls I knew had sad and sullen gray faces

With distant gay traces

That used to be there you could see where they’d been washed away

By too many through the day…

Twelve o’ clock tales.Then you came along with your siren of song

To tempt me to madness!

I thought for a while that your poignant smile was tinged with the sadness

Of a great love for me.Ah yes! I was wrong…

Again, I was wrong.Life is lonely again,

And only last year everything seemed so sure.

Now life is awful again,

A trough full of hearts could only be a bore.

A week in Paris will ease the bite of it,

All I care is to smile in spite of it.Ill forget you, I will

While yet you are still burning inside my brain.

Romance is mush,

Stifling those who strive.

I’ll live a lush life in some small dive…

And there I’ll be, while I rot

With the rest of those whose lives are lonely, too.

ES: “Lush” does have a dash of luxury too though, right?

BA: Right—the sparkle of the life just beyond your reach.

CB: Yes, absolutely—that sparkle is a great image.

BA: The sparkle of the gun, the sparkle of the writer’s life, the actor’s life, Berkmann’s bar. But things are so dark in reality…. I suppose there is hope there, too, as part of the sparkle just out of reach.

CB: Yes, Berkmann’s, where everyone wants to be for a few hours, inebriated & full of possibility.

ES: Sparkle of construction–the transition of the Lower East Side.

BA: Yes. All those new windows. All that gentrification.

CB: Which bring us back around to feeling guilty–we the gentrifiers. I’ll speak for myself…

BA: Oh, we the gentrifiers. Such guilt.

ES: But guilt’s not productive, right? Book writing, art making—are these?

CB: Some days yes, some days no hence my perpetual flirtation with nursing school.

BA: Yes, I think writing is productive… but what if it’s not *about* these things we’re talking

about?

CB: Everything is about these things, isn’t it? Hopes, dreams, failures of self and others.

BA: Oh, I mean—yes, I guess everything is about these things, I guess I just worry it doesn’t appear that way in my own writing…

CB: I know. I want to write about science! And fairies! And the rabbits who keep eating my garden! But even they fit in under those categories I suppose.

BA: Those pesky rabbits.