“Marriage imprisoned the mind,” muses a character in Annam Manthiram’s short story collection Dysfunction. For most of Manthiram’s characters, marriage is a condition of shared chronic misery. Obsessed with marriage or relationships, the unattached aren’t any happier—a college student stalks her ex-boyfriend; a middle-aged woman endures forty-plus bride-viewings (visits from potential grooms to decide whether she’s acceptable), and never gets chosen.

“Marriage imprisoned the mind,” muses a character in Annam Manthiram’s short story collection Dysfunction. For most of Manthiram’s characters, marriage is a condition of shared chronic misery. Obsessed with marriage or relationships, the unattached aren’t any happier—a college student stalks her ex-boyfriend; a middle-aged woman endures forty-plus bride-viewings (visits from potential grooms to decide whether she’s acceptable), and never gets chosen.

The collection’s fourteen stories can be divided into two general categories: short experimental pieces, and longer stories with a more traditional narrative structure. Manthiram applies these varied styles to map the territory of the unloved in disturbing and memorable ways.

The experimental works are stunning. “Variations on a Blossoming Marriage” is a brilliant piece, but difficult to categorize or even describe. Calling it a series of brief evocative glimpses of marriages does not do it justice. I’d rather quote a few of the Variations in their entirety. Under the title “Yellow Rose” we have this:

He always kissed me on the forehead. Before I do, respectful. After I do, macabre. A fossil of father.

And here is “Poppy”:

We did drugs together. I liked opiates because it always made me feel like I was standing on a ledge, waiting for him to catch me–like Superman. But he never did, the bastard.

“The Cottonwood Borer” is a small, two-and-a-half-page masterpiece. The first-person narrator recounts her mother’s memories of an idyllic childhood along the Rio Grande; then the story jump cuts to the mother on her deathbed, imparting a cryptic last wish to her daughter. We are given a few choice details to convey a sense of the life lived between those two endpoints, childhood and final days. This compression, the sense of a whole life opening out behind a few short paragraphs, echoes throughout Manthiram’s shorter works.

Some comic relief is provided in “Superheroes,” which begins by announcing, “Superheroes are not Indian.” Even here, the traits that are missing in superheroes hint at travails that ordinary mortals are left to deal with. “Superheroes,” we are told, “don’t need to get drunk on Saturday nights in order to forget what happened before, nor do they have to pray to a God that doesn’t listen.”

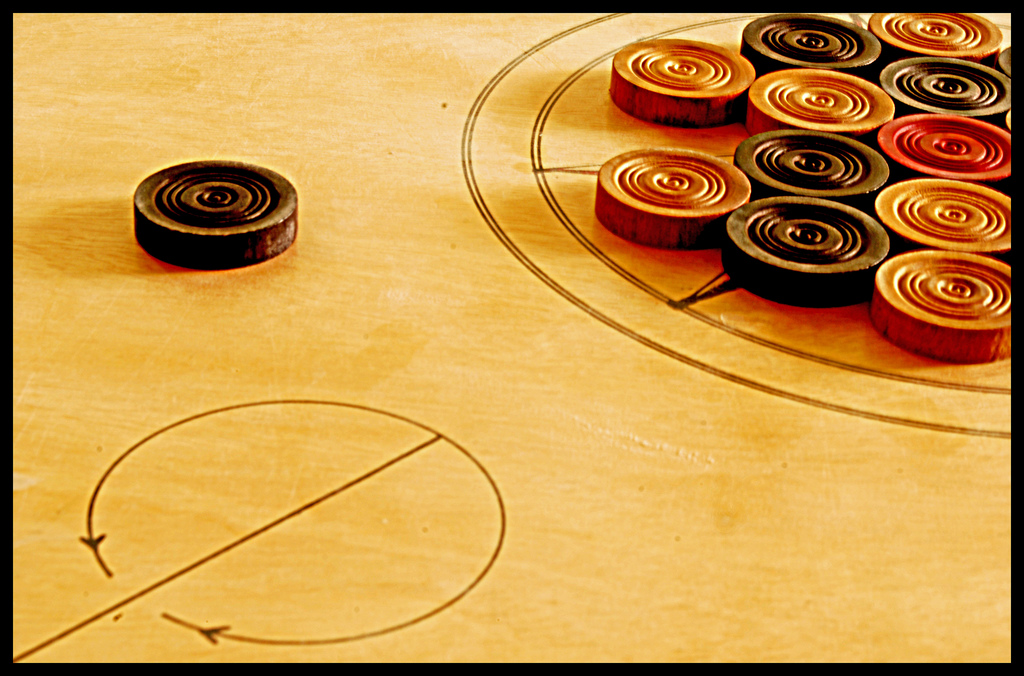

Of the longer stories, the standout is “Golconda, India, 1686,” narrated by Arpana, a sultan’s daughter, whose thought-provoking observations of palace intrigue are interspersed with excerpts from rules for the board game carrom. In sharp contrast to the protagonists of the other long stories, Arpana is highly educated, beautiful, and self-confident, and the events of her tragic life unfold on a grand scale.

If the protagonists of the other long stories are in some ways Arpana’s modern descendants, they are decidedly unspectacular in their misery. There is no grandeur, only bleakness, and the characters seem resigned to their dismal lives. One of them, the narrator of “The Reincarnation of Charmuda,” reads obituaries to comfort herself after repeated rejections from possible suitors: “Awareness of my own mortality made life more manageable,” she tells us. “I related it to the chaos theory–over time, all things lead to disorder. The same could be applied to life: the way our skin degraded, how our lives became less tolerable and our spouses more violent.”

The mothers in these stories tend to be cold and disapproving at best, nightmarish at worst. In both “When You Were Young” and “Asha Ma,” the protagonists’ mothers are verbally abusive and physically violent, determined, it seems, to crush their daughters’ spirits. Maybe because these two stories are the longest in the book, the specter of the monstrous mother looms over the collection.

The book’s most despicable figure, interestingly enough, is not a mother. The title character of “How Miriam Came to Learn about Love” is a college student who subjects her hapless boyfriend Jerry to withering insults and casual violence, then stalks him when he breaks up with her. Miriam is a person who pours hand sanitizer into the eyes and mouth of a semi-conscious flu sufferer, a person who tosses a gerbil onto the road (she had it in her trunk to bring to Jerry, and decides it’s no longer of use). Don’t look for a redemptive ending (not for nothing is the book’s title Dysfunction), but the author does provide a beautifully ironic twist: dreadful as Miriam is, she arrives at a moment of self-understanding that represents an improvement over the monstrous mothers of the previous stories.

Both chaos theory and the dauntingly intricate board game carrom could stand as metaphors for interpersonal relationships throughout Dysfunction. The characters, entangled in connections that are almost never nurturing or satisfying, may want to be superheroes but instead act more like random molecules, game pieces, or befuddled gerbils, buffeted by larger forces they don’t understand. Optimist that I am, I’m hoping the gerbil escapes unharmed.