For a long time, the publishing industry maintained that short story collections don’t sell. At best, they generate buzz for a forthcoming novel. But collections now defy that expectation. In part, their new popularity stems from the bite-size portion of a short story, as well as from the long-tail business model of e-commerce. Also, collections tap into a built-in audience at M.F.A. programs around the country, which venerate short story writers, since that form is easier to teach (according to Mark McGurl, M.F.A. programs in the U.S. have grown by over 673% since 1975). Some examples of successful collections include Edith Pearlman’s Binocular Vision, Benjamin Percy’s Refresh, Refresh, and Danielle Evans’s Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self.

For a long time, the publishing industry maintained that short story collections don’t sell. At best, they generate buzz for a forthcoming novel. But collections now defy that expectation. In part, their new popularity stems from the bite-size portion of a short story, as well as from the long-tail business model of e-commerce. Also, collections tap into a built-in audience at M.F.A. programs around the country, which venerate short story writers, since that form is easier to teach (according to Mark McGurl, M.F.A. programs in the U.S. have grown by over 673% since 1975). Some examples of successful collections include Edith Pearlman’s Binocular Vision, Benjamin Percy’s Refresh, Refresh, and Danielle Evans’s Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self.

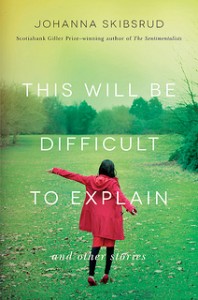

And now, W.W. Norton hopes, This Will Be Difficult to Explain, a new collection from Johanna Skibsrud, Scotiabank Giller Prize-winning author of The Sentimentalists.

This Will Be Difficult to Explain is a slim, lime-colored book with a picture of a lackadaisical girl on the cover. It holds nine stories in just one hundred and sixty-nine pages, but although the book feels light in the hand, the stories pack a concentrated, emotional punch. Throughout, the writing follows a particular kind of literary formula, a type of late-century naturalism mixed with minimalism, meaning the ingredients include unpretentious language, ordinary characters, and simple situations that, as the characters live through them, grow increasingly difficult. Instead of pyrotechnics, though, or melodramatic confrontation, the stories fade away with an image meant to convey the deep profundity of the human condition. Take, for example, the end of “French Lessons,” when the narrator reflects on a past employer. The Madame, an old blind woman, reveals that her son committed suicide, and later the narrator can’t stop thinking about it:

Later, she couldn’t help wondering if the boy had really done it like that (Madame’s forefinger, aimed at her throat), or if perhaps it had been performed somewhat differently, or even not at all, but that Madame could think—at that time—of only one foolproof method by which so great a sadness might be explained, or conveyed.

Many of the stories contain moments such as this, where a character’s small interaction with someone else leaves an enduring echo. The characters colliding with one another don’t share a pattern, and include many different types of people in different situations, from a father and his daughter to a visitor at a hotel and the waitress who serves him. Usually, though, these people remain strangers, at least in some sense, even though they are also drawn together by circumstance or accident, and each person is changed in the encounter.

So although Skibsrud has defied industry expectations by releasing a novel and then a collection, she will have no trouble amassing a following. And no one will question how or why she has appeared as a rising star among those who love literary fiction—in fact, it won’t be difficult to explain at all.

Extra

- Read an interview with Johanna Skibsrud on Maison Neuve.