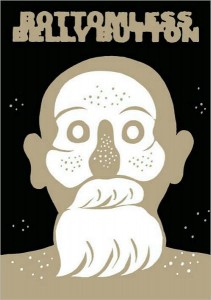

One advantage to working in the graphic-novel medium is its extraordinary capacity for detail. Without the need for description, and with the supposed thousand words per illustration, authors are allowed quiet moments of focus that might be dull or ponderous or even nigh-impossible to convey with straight prose. In Bottomless Belly Button (Fantagraphics), cartoonist Dash Shaw takes this technique to an extreme, decompressing what might typically, in prose form, be material for a short story or a novella, into 700 pages of evocative panels: three grown siblings reunite at their childhood home upon finding out that their elderly parents have decided to split up. Dennis, the eldest, reacts with the most outward frustration, while middle child Claire has her hands full with her teenage daughter Jill, and youngest Peter drifts through in a haze other twentysomethings may find familiar.

One advantage to working in the graphic-novel medium is its extraordinary capacity for detail. Without the need for description, and with the supposed thousand words per illustration, authors are allowed quiet moments of focus that might be dull or ponderous or even nigh-impossible to convey with straight prose. In Bottomless Belly Button (Fantagraphics), cartoonist Dash Shaw takes this technique to an extreme, decompressing what might typically, in prose form, be material for a short story or a novella, into 700 pages of evocative panels: three grown siblings reunite at their childhood home upon finding out that their elderly parents have decided to split up. Dennis, the eldest, reacts with the most outward frustration, while middle child Claire has her hands full with her teenage daughter Jill, and youngest Peter drifts through in a haze other twentysomethings may find familiar.

We don’t just follow the characters saying goodbye to the family unit as they know it — we glimpse their routines and private moments. Shaw slows down time, sometimes spending several pages on simple acts like jogging or undressing, and he pauses completely to display Wes Anderson-style maps of the household or photos from family albums. All of these details add up to a much larger picture of a family neither cripplingly dysfunctional nor completely in sync: when Dennis and Peter share an awkward hug or Claire tries to relate to her daughter, you can feel the space between all of them.

Throughout, Shaw imitates the simplicity of newspaper comics—everything is portrayed in brown-and-white, for one—for a cumulative, rhythmic effect. He uses labels and decidedly non-onomatopoeian sound effects (rather than action-style “bam” or “pow,” actions are accompanied by “poke, poke” or “shrugs” or “smooths-out”) to access the directness of comics while never simplifying the actions or emotions. The similarly comics-only conceit that Peter be drawn as a (humanoid) frog, while everyone else is a normal human, fares less well. As a symbol of alienation, it’s obvious (and a little confused, since just about everyone in the book feels alienated from someone else); as an artistic gambit, it seems arbitrary given how striking Shaw’s humans look.

It may also seem arbitrary the way the story ends without much resolution for anyone, but it’s not; perfectly, the narrative ends when the family reunion does. Shaw doesn’t yet have the authorial voice of alt-comics mainstays like Daniel Clowes or Adrian Tomine—that sense that no one else could have written or drawn his story as well. But I can’t wait to see him continue to develop, hundreds more pages at a time.

Preview Bottomless Belly Button with this slide show from Fantagraphics or the following trailer (created by Dash Shaw himself):