“The Bloody Countess” Erzsebet Bathory gained immortal fame as one of the first female serial killers; she was accused of brutally torturing and murdering over six-hundred young women.

“The Bloody Countess” Erzsebet Bathory gained immortal fame as one of the first female serial killers; she was accused of brutally torturing and murdering over six-hundred young women.

But the countess was also a powerful widow holding sway over a considerable inheritance of land and money, and her family’s political allegiances were a problem for the regents. Was she really an unrepentant, psychopathic murderer—or was she simply a political obstacle to the king? Was she really bathing in the blood of her victims, or was she herself the victim of a witch hunt? Such questions haunt the pages of The Countess (Crown, 2010), Rebecca Johns’s lively historical novel about Countess Erzsebet Bathory of Hungary. Johns beautifully reconstructs the complexity of this 17th century scandal and brings alive the woman behind the myth.

When I picked up The Countess, I didn’t know what to expect. I read mostly literary fiction, so I wasn’t looking forward or hoping for a Gothic tale. I knew Johns’s work from her debut, Icebergs, a quiet novel about ordinary people’s struggles to overcome the extraordinary emotional damages of war. I had been so impressed with that novel’s understated emotional power that I decided to give Johns’s vision of the evil countess a try.

When I picked up The Countess, I didn’t know what to expect. I read mostly literary fiction, so I wasn’t looking forward or hoping for a Gothic tale. I knew Johns’s work from her debut, Icebergs, a quiet novel about ordinary people’s struggles to overcome the extraordinary emotional damages of war. I had been so impressed with that novel’s understated emotional power that I decided to give Johns’s vision of the evil countess a try.

From the moment I started reading, I couldn’t stop. This fictional historical memoir drew me in with a voice irresistible for its clarity, intelligence and modern subtlety. Hardly the truculent blood-lusty pervert, Countess Bathory comes across as an intelligent woman who from a young age understands too well the responsibilities laid on her shoulders: to not only preserve the family’s name and riches, but to care for her youngest siblings against political turmoil, war, and shifting political allegiances. In the character’s own words:

For a long time I was shocked by the idea that the fate of the family would fall on me, that my little sister Zsofia would depend on me to find a husband who would love me and protect her for my sake. I could not imagine that any man would love me as my father loved my mother.

Throughout the novel, Bathory juggles the restrictive proprieties imposed on women’s conduct with the ruthless political maneuvers that her status and wealth demand. Her family’s wealth baits jealous enemies and men all too willing to play on Bathory’s heart for political advantage. When Bathory becomes a widow and her children are too young to take over the family estates, she struggles to protect her sons’ and daughters’ inheritance against those who threaten to steal it. Who could fail to sympathize with such a woman?

For most of the book, I sided with Bathory. I admired her self-control, her inner fortitude, and her boundless love for her children. I felt her wounded pride when less then reliable men played unfairly with her. And for most of the novel I believed her to be a woman who had everything but what she most longed for: love or even respect from the men in her life. Even her son, who provides the pretext for the letters that compose the story, fails to visit her or even send a kind message when she’s in jail, waiting for death to end her misery and loneliness.

But, readers must wonder, is the countess innocent? Johns is a masterful psychologist. She takes care to establish clues to Bathory’s possible neurosis early in the novel when the countess recounts witnessing—as a child—the execution of a gypsy man who sold his daughter to slavery. The gypsy man is sewn alive inside the stomach of a dying horse, and is left there to slowly die of thirst, hunger, and infection. The young countess visits him on the hour of his death, refusing him water. As she relates:

[…he] opened his eyes, struggling and cursing. I spit in his face, and the white spittle caught in his mustache and hung there like a bit of spider silk. I was never so satisfied as I was at that moment, watching him suffer.

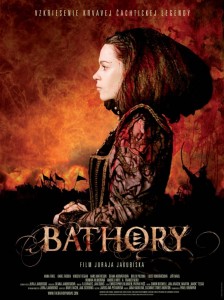

A poster from *Bathory*, Juraj Jakubisko's 2008 film about the Bloody Countess

The narrative suggests that this disturbing reaction invokes a curse or, at the least, calls bad luck upon her. Far from resonating with hocus pocus, this moment establishes the basis for Bathory’s most profound emotional distress: the fear that if she can’t make a man love her, she will become as powerless as the girl who was sold into slavery. She especially resents the gypsy man’s betrayal of his daughter; betrayal is another theme that resonates with her life tragedies. This event also establishes the environment of superstition that ruled the Middle Ages and became a deadly trap for Bathory.

Later in the novel, it becomes clear that Bathory remains affected by that childhood event; the gypsy’s dying words revisit her during the most traumatic moments of her adult life—and there are many such moments in this novel. The countess is married to a cold, uncaring man, seduced by indifferent lovers, disrespected by the servants, and devastated by the loss of three of her children.

It is so heartbreaking to see Bathory’s affections crushed at every turn that we forget her historical reputation and hope instead for a happy ending. The beatings and the rather creative punishments of the servant girls (she forces one to breastfeed a wooden log) seem at first only a footnote to the more compelling story of her emotional devastation.

Rebecca Johns

Even as the novel begins to unravel the mystery of the servants’ deaths, Bathory is such an eloquent character that it’s easy to ignore even the most obvious clues: a reader could long hold onto the belief that Bathroy was just an unwitting enabler to the perversions of her more trusted servants, to whom she delegated the management of the household.

It is only late in the novel that the reader fully witnesses the ravaging effects of the countess’s emotional damage as it capitulates in her blackout rages. In a riveting scene, Johns unleashes her most brilliant storytelling gifts, bringing us into the fragmented, haunted mind of the countess when she’s under the spell of her most repressed rage, revealing even in that moment of absolute monstrosity a compelling vulnerability:

A cracking noise, like the breaking of stone, and the room grows dim before me, blackens. I am alone in the darkness, and then, as if from a great distance, colors come back to me, sounds, light. There is a girl in front of me, a girl crying. Her nose is bright with blood and her eyes tear, making tracks in the dirt of her face and the blood…How small she looks, how frightened. For a moment, I wonder what her days are like, what love there is for her, whether she feels fear, or anger, or pity, or love. Whom does she love? What have those she loves done to her? There is blood on her face, running off her chin in little spins and rivulets. I’m not sure how it got there.

The real horror of Johns’s version of this historical monster is that Bathory is not only likeable, a woman we would not hesitate to welcome if we’d met her in real life, but, like most serial killers, she is comfortable balancing her dark side with her generosity and sense of justice. The most lasting effect of Johns’s The Countess is the uneasy feeling readers get that there may be a monster within each of us, concealed behind thick curtains of false ethics and self-justifications.

For the reader who seeks sophisticated characterizations and unreliable narrators, Johns’s work is thoroughly satisfying. She constructs a complicated character whose unrepentant confessions reveal the damaged mind of a woman raised to strive for all the most false and superficial values, a woman whose talents and ambitions become so focused on fleeting and unrewarding pursuits that the results can only capitulate in despair or madness. That Bathory refuses to crumble to self-pity is the spring upon which her disturbing late-life behavior feeds. Her fears give way to a mental breakdown that resolves itself, literally, in bloody murder.

By the end of the novel, I felt all the irony and perverted cruelty of Bathory’s punishment. Not only is the countess trapped in her fairy tale archetype of evil, but she also has the unfortunate fate of experiencing—literally—the restrictions imposed upon her gender by her time: she is walled alive inside a tower in her own estates, abandoned and reviled by family and friends.

The Countess is a complex and artfully constructed story about a powerful spirit perverted by oppressing values, political ruthlessness, and disloyalty, capitulating in a morbid slaughter whose realistic rendering is far more frightening than any fantasized demon vampire plot. Rebecca Johns proves that real-life horrors, the horrors of war and mental damage, are far more terrifying than any Gothic fantasy. I bow to Johns for transcending multiple genres and writing yet another eminently compelling story.

Further Links and Resources

– Learn more about Icebergs, Rebecca Johns’s first novel, at Powell’s Books. And pick up a copy of the Winter 2010-2011 issue of Ploughshares to read a story by Johns, “Perpetua in Glory.”

– You can read Laura Valeri’s interview with the author at The Mojito Literary Society, and here is a widely distributed Q&A with Johns, via Reuters.

– On her blog Illiterati, the author offers this fictional interview with Erzsébet Báthory.

– Would your reading group like to talk to Rebecca Johns about The Countess? Fill out this form on the author’s website.

– Bathory is a frequent subject of the arts and popular culture, inspiring novels, plays, films, comics, operas, metal bands, and even toys–like this doll in a blood bath.

– Interested in some cinematic takes on the legend of the Bloody Countess?

- Here is a trailer from Bathory, Juraj Jakubisko‘s 2008 film about the countess; Anna Friel stars in the title role.

- And here is a trailer from Julie Delpy’s 2009 film (which she directed and starred in), The Countess: