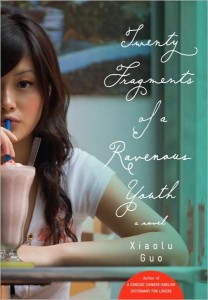

The dust jacket of Xiaolu Guo’s Twenty Fragments of a Ravenous Youth depicts not one but three young Chinese women: on the front, a doll-eyed girl sips a pink milkshake through pursed, glossed lips; on the spine, she leans against a subway pole with eyes closed, as if exhausted by the title that slices across her face; and finally, on the luridly red-tinted back, she crosses a darkened street, hurrying out of the photo head-first. You might read these women as Morning, Afternoon, and Night; or as Innocence, Disillusionment, and Corruption. Either way, the cover reflects the contrasts in this slender novel, which focuses on the disjointed existence of Fenfang, a young woman who has come to Beijing to seek her fortune.

The dust jacket of Xiaolu Guo’s Twenty Fragments of a Ravenous Youth depicts not one but three young Chinese women: on the front, a doll-eyed girl sips a pink milkshake through pursed, glossed lips; on the spine, she leans against a subway pole with eyes closed, as if exhausted by the title that slices across her face; and finally, on the luridly red-tinted back, she crosses a darkened street, hurrying out of the photo head-first. You might read these women as Morning, Afternoon, and Night; or as Innocence, Disillusionment, and Corruption. Either way, the cover reflects the contrasts in this slender novel, which focuses on the disjointed existence of Fenfang, a young woman who has come to Beijing to seek her fortune.

Told in short, titled sections—the “fragments” of the title—the novel follows Fenfang as she escapes her life on a sweet potato farm for a new start in the city, struggling towards independence, maturity, and purpose on the way. The narrative jumps back and forth in time, often starting in the present and then cutting into flashback; Fenfang, lost in her memories, moves from apartment to apartment and job to job so often that she—like her reader—sometimes forgets where she is. The overall effect captures the chaos and confusion of modern urban Beijing, as well as the relentless driftlessness of Fenfang’s life.

Throughout, Guo infuses Fenfang’s voice with wry, self-mocking perspective. Looking back on herself, she sees “a seventeen-year-old who thought that drinking a can of ice-cold Coke was the greatest thing ever.” As she moves to yet another run-down apartment, she says, “I’ve been blessed with cockroaches in every place I lived in Beijing, but it was in the Chinese Rose Garden that I was truly anointed.” Although Twenty Fragments was originally written in Chinese, then translated into English, it doesn’t read like a translation; in fact, Guo rewrote in English on top of the translation, and her language is often startlingly sharp. Even more remarkable, she does little cultural translating for the reader. When she refers to “Longevity Noodles,” there’s no encyclopedia-type paragraph—as there often is in literature about other cultures—explaining the customs of the country. Likewise, Guo’s delightful phrase “Heavenly Bastard in the Sky” appears without explication. This confidence in the reader, and refusal to turn the novel into a Textbook About Chinese Culture, is refreshing.

That light touch works less well with the characters, however. It’s hard to get a sense of who these people are, what they care about, why they do what they do. Important moments happen off-screen: Fenfang goes on a date, and one white space later, she’s moved in with her new boyfriend—and the rest of his family—in their one-bedroom apartment. At other times, the story moves in fast-forward; that first date happens on page 20, but midway down page 21, three years have passed and the relationship—the most significant in Fenfang’s life so far, and arguably in the entire the book—has become stale and stifling.

This breakneck pace may be in keeping with the dizzying speed of modern life in Beijing. But some events are so abrupt they come off as bizarre, such as the mother and daughter who are run over by a van in front of Fenfang on her first night in the city. Their bodies are scooped up by the van’s driver, leaving nothing “but a bit of blood on the pavement”—and a conveniently empty apartment, which Fenfang appropriates for a time before, inexplicably, moving on. Perhaps these moments are meant to highlight the soullessness and impersonality of the Big City: it is indeed chilling how no one seems to notice, or to care. But in other places, that abruptness seems to stem from a lack of character depth. When Fenfang’s American lover visits her apartment, she is arrested by mistake while he’s in the bathroom. His only response? To leave a note: “Fenfang, Are you OK?? Call me!” And, in the next breath: “I need to talk to you about the future. I’ve decided I’ve gotta go home otherwise I’ll never finish my fucking PhD. I’m flying back to Massachusetts the day after tomorrow.” Exit the American. We sense the suddenness of this departure, but the effect is more comic than tragic.

Even Fenfang herself seems perplexed about why these things happen. “How was it that I could sit on the floor of the 315th apartment in the Commercial Success Condominium and not remember how I got here?” she wonders. After calling her violent ex-boyfriend—who’s been stalking her—she admits, “I don’t know why I did it … What on earth had possessed me to revisit my past?” The reader has no idea either. Fenfang is unsure exactly how these men drift in and out of her life: “Ben, who came into my life I can’t remember how. Maybe it was in a bar I liked called Dirty Nelly, or at a bookshop, the one that sells foreign books.” She excuses these lapses of memory through a folk saying: “In my village, the people used to say that a buffalo only remembers things for a month. I think I must be a buffalo.” Yet she has no trouble remembering the exact geographical location of Boston (Latitude 42° North, Longitude 71° West, -4 hours GMT), which she cites repeatedly.

Guo strives to make the metaphorical literal: a young woman’s life and sense of self become hazy and indistinct in the bright lights of the big city. But it’s difficult to understand Fenfang when, despite the retrospective narration, she remains confused and detached. “Maybe that was why people thought I was heartless,” she says. “Apparently my face often had a blank expression.” Though the novel is told in the first person, Fenfang’s emotions are deeply hidden, and the face she presents to her audience is similarly blank.

The most sharply drawn, most engaging, and most enticing character in Twenty Fragments is contemporary Beijing itself. The novel is most vibrant and alive when Guo gets down to details, and the city sparkles in her descriptions, which are sharp, fresh, and free of the clichéd exoticism of many China-set novels. In Fenfang’s hometown, there is one communal book, The Adventures of the Shadow Samurai, that has “been pored over by every literate person in the village” until its covers are lost and its pages marred. Guo highlights the mix of optimism and ridiculousness that comes along with modern city living:

I took a ‘Crazy English’ course, where they believed that you could master English by shouting very loudly. I enrolled in a Wubi typing course where you had to speed-type Chinese characters on an English keyboard. I even took a theory course for those learning to drive, though I didn’t have a car and was totally confused by Beijing’s maze of highways and overpasses.

And throughout, the city pulses relentlessly in all its overwhelming, messy glory:

No matter if it was morning or afternoon or the middle of the night, you would always find a sea of trucks and vans and cars—green state-operated cabs, crowded minibuses, private cars with their tan leather interiors and dogs on the back seat…You smoked the taxi driver’s smoke as he spun sharply around a corner, you smoked the local party leader’s smoke as he tried to establish order at a meeting, you smoked your boyfriend’s smoke whether he loved you or not. Chinese-made cigarettes, foreign imports, dodgy rip-offs. The city was in a permanent fog.

In passages like this, you can see the “cramped side streets where the walls were like the scales of a fish—tall shelves tightly packed with pirated disks.” And you can sense the promise behind this befuddling, bewitching city, what lures Fenfang to Beijing in the first place: “You could find anything you wanted here.”

Read excerpts from Fragments 1, 2, and 3