Though I’d first heard of Charles Baxter as a high school student, reading the highly praised Feast of Love, and though I had been aware of his presence at the University of Michigan, when I was an undergraduate there, and even though I’d studied his stories and title novella in Believers (that novella being my favorite of all his work) while an MFA student at Emerson College, it wasn’t until my life brought me to the San Francisco Bay Area that I was able to meet and take a class with the writer. I had recently reviewed his then-latest volume, Gryphon: New and Selected Stories, and discovered that he was coming to Stanford University, where I work, to serve as the Stein Visiting Writer.

Charlie allowed me to audit his undergraduate class, but because I wasn’t a student he proposed—or perhaps, more honestly, “justified”—doing so with the agreement that I would give as example to the other students my perspective of what it’s like to graduate from an MFA program. It was a generous deal. His hybrid literature seminar/workshop played a role in developing my own Creative Writing teaching method. I also modeled in part my attitude about creative writing and the culture surrounding it on his. Generous and friendly in general, Charlie is critical but also encouraging, describing the career of a writer as a “long path,” a phrase that to me means it is difficult, perhaps labyrinthine, ultimately rewarding, and, most important of all, surprising. Charlie has a deep love for the short-story form, a love that demonstrates how vital the practice of writing can be, regardless of the “fame and fortune” often seen as the only justifiable outcome of what all writers know is very hard work.

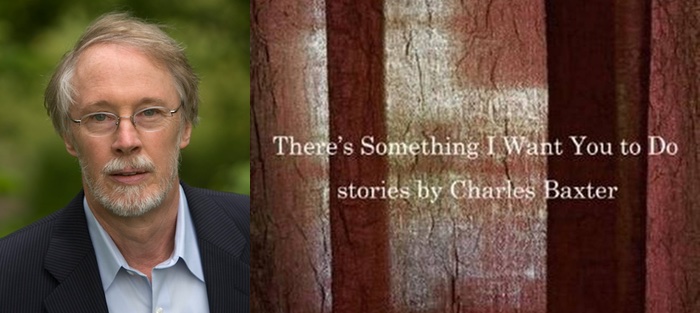

Charles Baxter began by writing poetry, publishing two volumes of poetry in the 1970s. Although he has continued writing poetry, Baxter is better known for his work in fiction. Since his debut novel, First Light, in 1987, he has published four other novels, six works of short fiction, and two books of essays on the craft of writing—invaluable resources for the practicing writer. His latest volume is There’s Something I Want You to Do: Stories, published this week by Pantheon.

Interview:

Ian Singleton: Thanks for granting my request to do this interview, Charlie. Let’s talk about requests, since that’s a theme in your new collection, There’s Something I Want You to Do. Each story has a moment when a character says, “There’s something I want you to do,” which leads to a request. The stories’ titles each come from virtues and vices. How are those two themes related in your work, requests and then virtues and vices?

Charles Baxter: A couple of ways. I came at this in a very unmethodical way. I wasn’t thinking systematically when I put the book together. I arrived at this arrangement just from a kind of a coincidence. I had seen a performance of Hamlet at a local theater here in Minneapolis, and I was struck by the way that play starts with the ghost of Hamlet’s father asking him to avenge his death and to honor his mother and to remember his father, all these requests. And it struck me: that’s a hell of a wonderful way to get a dramatic story started, just to ask someone to do something, particularly if it’s dangerous, or possibly unethical. It brings up issues of loyalty, issues of power, of your will, of your ability to do what’s been asked of you. And I thought: Well, I don’t know why a short story couldn’t operate by some of the same means.

Soon after that I saw another production of a Shakespeare play, King Lear, which also starts with a request moment, with Lear asking his daughters to tell him how much they love him…which, you know, is absurd. But by then I thought that maybe I was onto something, something useful at least in constructing the interior drama of these stories. And then I happened to think about the [Krzysztof] Kieślowski series of stories that he did for Polish television, The Decalogue, which I had seen many years back, and I thought, Wow, I wonder if I could put something like that together without any actual moral lessons. Because I didn’t want the book to be a series of moralizings. I just thought, if you ask somebody to do something, you’re invoking a kind of moral world one way or another.

So, the requests, as you say, invoke a moral world?

I think so. I think the request has to rise above a certain trivial level. If I’m in the room with you and I say, “Hey, Ian, would you get me a cup of coffee?” you could say, “Yeah, sure,” or “No, I’m busy right now,” it doesn’t have the same effect. But if I say, “Hey, Ian, there’s been a dog in the neighborhood that’s been soiling my lawn. Could you go out there and kill it for me?” You know, it’s a different kind of story.

Yeah, I’d have to think about that before I killed the dog.

[Laughter.] Yeah, any of us would. That’s the kind of thing that, I think, gets interesting in a story, you know, when you start to wonder, Hey, would I do that? I don’t know if I’d do that?

Is there a reason why you chose linked stories with recurring characters? Sometimes the same character is in one virtue story and one vice story. Why choose to do that?

The trivial answer is that I was reading one of the early ones in Erie, Pennsylvania. I think it was the U Penn-Erie. And I tried to explain to the audience what I was working on, and a kid in the audience, Kyle Kerr, said, “Are the same characters gonna be in the vices or the virtues?” I hadn’t thought of that, but maybe they are, and it turned out they are. I mean, there’s an obvious point here, which is that everybody commits virtues and vices. And I just thought it would be interesting to keep the characters going and have a major character in one story be a minor character in another. It was fun to play with. I like patterning. As a writer, I like patterns. I always have, and messing around with the structure of a book…I wanted the book not to look like other people’s books. And to have a kind of crazy logic of its own.

Yeah, because you said it wasn’t systematic or methodical, yet you have five virtues and five vices. I couldn’t figure out what your system was, because I’ve always heard of the seven virtues and the seven deadly sins, and they each have their pairs.

Not this time. This is my decalogue. This is my own version of all that. No, if I had used the classic virtues and vices and the way they’re defined, I would have been hemmed in. I wouldn’t have had the room I wanted.

That makes me think of “Chastity,” since in that story you give your own take on the virtue, with the idea that “irony is the new chastity.” That really stuck with me. It has a double side to it, right? Sarah’s irony is a form of chastity. But chastity’s not a virtue if it prevents reproduction, and Sarah’s overdoing it on the irony seems to put a distance between her and the story’s protagonist, Benny Takemitsu.

Sarah is one of those characters in your stories who seem to be kind of strange, inscrutable, even sibylline. The first story, “Bravery,” has another woman, Susan, who takes “pleasure in seeing [boys] flummoxed.” Can you talk about writing such characters as opposed to writing more straightforward ones?

Well, in the next story, “Loyalty,” there are two central women, the first wife, who goes into post-partum depression that she can’t get out of and really undergoes a series of mood disorders after that. But then there’s the second wife, Astrid, who’s very straightforward. Who’s a wife and mother and a nurse, a serious professional, and who’s very down-to-earth. I think that’s also true of other stories and characters of mine. In The Feast of Love, Diana is a very strong, smart woman, who’s not inscrutable.

Well, in the next story, “Loyalty,” there are two central women, the first wife, who goes into post-partum depression that she can’t get out of and really undergoes a series of mood disorders after that. But then there’s the second wife, Astrid, who’s very straightforward. Who’s a wife and mother and a nurse, a serious professional, and who’s very down-to-earth. I think that’s also true of other stories and characters of mine. In The Feast of Love, Diana is a very strong, smart woman, who’s not inscrutable.

I think what happens is that, when you’re writing fiction, you have a couple of choices in finding the source of the story. One of them is to make the situation peculiar, or dangerous, and the other is to have characters who are somewhat unusual, and, in those stories, in anybody’s stories, you do one or the other. You’re often trying to find an unusual character, somebody who isn’t bland, and who’s fascinating and who has some resemblance to what’s going on in the world. When I was writing “Chastity,” I was trying to get at a certain kind of character who is uncomfortable with intimacy. She’s a stand-up comedian. And I think there are people like that out there. I mean, most of the time they’re just texting on their cell phones. But they also, particularly young people, people in their 20s, in a professional class—I noticed this around Stanford—tend to be very ironic all the time, jokey, wise-cracking types. And I think there’s a lot of humor to that, but there’s a dark side to it as well, and I tried to get that into the story.

I think part of that might have to do with Stanford being located in Silicon Valley, where that’s a chronic problem.

Well, I think it is, actually, and I think that’s true wherever professional, managerial people, who are very young, are making a lot of money. You get both idealistic and cynical, both at the same time.

That’s an interesting observation, which makes me think about class. You brought up “Loyalty,” which includes yet another character, who then appears in “Avarice,” Wesley’s mother. I really enjoyed that story as well, especially her voice. There’s a class difference between her and somebody like Benny Takemitsu. Can you talk about how you write characters like Benny or characters like Wesley’s mother differently?

You mean Dolores. With Dolores, who hardly appears in “Loyalty,” and I don’t think she gets a direct quotation, I thought, who is this woman? Who is a Christian, and who imagines the end times?

I love the line that she is “immune to surprise.” I have people in my family like that. Sorry to interrupt.

Oh no, that’s okay. Thank you. One of the things I was aiming for was a character who was dying and was still upbeat, who never felt despair and never felt anger about it, or if she did, she only felt it for a moment. So, I set about writing this odd combination of a woman who is Christian, upbeat, and dying. Wesley is a very smart guy. I mean, he’s a garage mechanic, but he’s a very smart guy, and so is she. When “Loyalty” first came out and then was anthologized, a couple people said to me, “I don’t think garage mechanics are usually this smart.”

I have to admit I thought that for a second, but I don’t think I can say such a thing.

Well, I’ve met a lot of really smart people who do work like that, really, really smart people who have simply chosen that kind of life. So, I wanted to make both of them very perceptive and interesting people. I hope I succeeded. It’s not for me to say. But I thought it was important to have some mixture of social classes in the book.

I think that makes the book much richer. There’s a story called “Time Exposure” from Believers with a similar kind of character. Or another story, “The Winner,” with some of the class resentment Dolores has a little of.

Yeah. A whole lot of class resentment. I share it.

But it’s much more dignified, I think, with Dolores. Maybe this has something to do with that religious outlook she has. Since you wrote about the virtues and the vices, how has religion influenced your writing? Or has it at all?

Oh, it has. I grew up as an Episcopalian. And on my father’s mother’s side, there were preachers, ministers, theologians. I use this subject as a way of talking about inner worlds and perception of the otherworldly, the sense of mystery that is often in our lives, whose origins we can’t know. That turns up a bit in “Chastity,” the idea that there may be a God, but we can’t say anything more about God than a dog can say about Mars. A dog is incapable of understanding that there’s a planet called Mars. And we may simply not have the cognitive, intellectual equipment ever to understand God. It’s a subject that’s turned up in a lot of my books, Shadow Play in particular, and Believers. It’s a preoccupation, and I deal with it any way that I can.

Oh, it has. I grew up as an Episcopalian. And on my father’s mother’s side, there were preachers, ministers, theologians. I use this subject as a way of talking about inner worlds and perception of the otherworldly, the sense of mystery that is often in our lives, whose origins we can’t know. That turns up a bit in “Chastity,” the idea that there may be a God, but we can’t say anything more about God than a dog can say about Mars. A dog is incapable of understanding that there’s a planet called Mars. And we may simply not have the cognitive, intellectual equipment ever to understand God. It’s a subject that’s turned up in a lot of my books, Shadow Play in particular, and Believers. It’s a preoccupation, and I deal with it any way that I can.

How does this make your style different than that of, say, strict realism?

Well, “strict realism”—what is that? But in my work there’s always a world within our world: something close, nearby. It’s our light and our darkness, our inner life. Religion understands that world, or at least sometimes it does.

This is in “Chastity,” at the end, where it mentions myths and fairy tales, kind of as a relief: “In myths and fairy tales, the stepmother…but…” Then it ends like a fairy tale, or a folk tale, which is very different than most of your endings, I would say. And I was reading another interview that you did with Jeremiah Chamberlin [for Glimmer Train], and you say that you can never end with a car accident, as a rule. Then your story “Gluttony” ends with a car accident. I guess you said it was more of a guideline than a rule.

[Laughter.] I stole that business of guideline vs. rule from Ghostbusters.

I thought that was a funny break of your own rules, or guidelines. We talked about this once before, and you said Stanley Elkin told you in a class that a writer should never have a dream in a story, but I think there’s a story with a dream in his Criers and Kibitzers, Kibitzers and Criers [Dalkey Archive Press, 2000].

[Laughter.]

So, finally, would you talk about your approach to endings, with exceptions and otherwise?

Any working writer usually doesn’t have more than an intuition about where the ending ought to locate itself. You don’t think these things out as abstractions, you work them out practically. There’s an idea going back to Aristotle, that you’re often looking for the moment when the situation reverses itself or reveals itself, or something comes up to the surface that makes the whole story suddenly illuminate the characters or the situation. I think David Mamet says somewhere that a good ending answers the question that the story has been asking in a way that seems inevitable and surprising. The protagonist may not have understood what was at stake, but suddenly she/he and the reader simultaneously realize it. In “Gluttony,” Eli, the doctor, comes to realize that he does love life, and in a way he has to fight to survive. But the story doesn’t end with the accident the way “Saul and Patsy Are Getting Comfortable in Michigan” does. Elijah has the accident, and then he has to climb out of the ditch, as my brother once did. The story is dedicated to the memory of my brother, who was overweight and often fell asleep behind the wheel, and one time had to do what Elijah does to live. Otherwise he would have frozen to death. I think endings tend to reveal themselves. You just keep writing and writing and writing, and sometimes you come to a point that you just feel that the situation has opened up and something arrives on the scene, and what was at play in the story resolves itself, and there’s a kind of clarity that’s achieved at the end. Often, you don’t know what it’s going to be when you start. But I like it when it reveals a sort of moment of beauty, in one way or another.

You’re right—it doesn’t just end with the accident. It’s actually everything that happens afterward, that often is left out of the Hollywood ending, the effects of violence.

When you think of Toby Wolff’s story, “Bullet in the Brain,” who would have guessed that that story’s ending would be a sentence: “Shortstop is the best position they is”?

I mean, that’s glorious, that’s a beautiful ending, and only Toby could have thought of it.

The focus on language.

The focus on language…the focus on something luminous, something beautiful.

Beautiful, and it reflects back on the character, because he prides himself on being this critic, then it’s something like “Rosebud.” And I suppose you wrote “Gluttony” after the accident you were in back in 2011?

Yes, I did.

There’s some frightening similarity between that and your brother’s accident.

Yeah, and my driver in the limo had fallen asleep. I didn’t mention that to the police, because I didn’t want to get the guy in trouble, but he had fallen asleep behind the wheel. That’s why we went over the shoulder and went tumbling down the ditch.

It’s amazing that you were worried about getting him in trouble.

Speaking of writing based on things that have happened to you, “Believers” might be my favorite of all you’ve written.

It’s my favorite too.

Tell me again what it’s based on?

It’s based on travels in Nazi Germany that my stepfather took with his first wife and a German-speaking priest, whom they took along with them. The rest of it was just invented. Except for the part about jumping up on the running board of Goebbels’ limo, which she did.

There’s something about the beginning. It feels like there’s a desire…it’s the story of a priest who has become a father. So, right there is an immediate story, of course. But you don’t dwell on that. I felt like there was a desire to have a life that wasn’t there, that’s only implied. Rereading it, I thought about my own family and upbringing, my own desire to want a different kind of upbringing or a different kind of background, at least to try it out. Is there a desire in that novella, or in your work in general, to live out another life?

There’s something about the beginning. It feels like there’s a desire…it’s the story of a priest who has become a father. So, right there is an immediate story, of course. But you don’t dwell on that. I felt like there was a desire to have a life that wasn’t there, that’s only implied. Rereading it, I thought about my own family and upbringing, my own desire to want a different kind of upbringing or a different kind of background, at least to try it out. Is there a desire in that novella, or in your work in general, to live out another life?

I think many writers have that. Most of us have that desire. Once you become tired of writing about yourself or people you’ve known, if you’re a fiction writer, you almost automatically start to become very curious about how other people have lived, and you try to imagine yourself as somebody else, a man or woman, somebody young, somebody old, somebody gay, somebody straight. For me it’s one of the great pleasures. I don’t want to write about myself anymore, I’m tired of myself. I want to imagine what it’s like to be somebody else. It’s not that I actually want to be somebody else in the world. I’m okay, I guess, being myself, and I’m stuck with it anyway. There’s nothing I can do. But I do like to imagine what it’s like to be other people. I think most fiction writers do.

Thinking about other people’s interests, other people’s needs and wants, and going back to “Chastity” with that irony, which I think you are implicitly criticizing, is Sarah and Benny having a family an antidote to that? Now they have to take care of somebody, and it’s really difficult to be ironic. I’ve seen people like that, who become parents and have difficulty maintaining that irony afterward.

That’s exactly right, and I think that’s very acute. I’ve seen some people who do it when they’re in company. But when you’re alone with your spouse, there’s no point in irony any more, not when the baby’s crying.

And the baby’s not going to get that irony.

No. [Laughter.]

I’m going through that right now.

Oh, right.

So, I’m absolutely sure of that.

How old is your baby now?

She’s ten weeks.

Wow. Congratulations. It’s an intense time. It’s a great time. But when you’re a young parent, when I was, I was just tired all the time, and I was scared that I was doing the wrong things and all of that, but there’s nothing like it.

Another interviewer asked you if there was ever a moment when you felt like you had “made it.” And you said, “No. That moment will never be.” Was there ever a crucial moment when you felt like giving up on the ambition of the writer, whatever that is?

Yes. Around 1978 or ’79, I had written three or four novels in succession, and none of them were published. I couldn’t get an agent. I didn’t know what was wrong with my writing, but something apparently was, because even my wife didn’t finish one of these books. The first thing I thought was I’m not going to write any more novels. And the second was I’ll write a story about not fulfilling my life as an artist. I thought Maybe I’ll just end up writing criticism for the rest of my life. So, I wrote a story called “Harmony of the World,” which in my mind was about how I was going to give up writing fiction. And that story kind of turned things around, because it was printed, and then it was anthologized in a couple of places. So, it gave me a sort of second life. It gave me some hope, that story. That story did it.

So, if you had to pick, would you rather write short stories or novels?

Short stories. I love reading other writers’ short stories. I just wish there were more of an audience for them. It’s such a beautiful form. Everything is possible in a short story. Novels often tend just to bore me. They seem laborious and padded. I like the poetry of short stories, really.

That makes sense considering you started as a poet. Last one, even though I think you already answered this. If you hadn’t become a writer, if you didn’t have a good, solid job teaching creative writing, what else would you do and would it involve language in some way? You said you’d have been a critic. Do you still want to stick with that answer?

[Laughter.] I think I have to. I would have been a teacher. I don’t know that I would have ever made a good scholar, but I think I would have been an okay critic. I don’t know how I would have avoided doing some creative writing. It just seems like, whether I had any audience for it, it was still something I probably would have wanted to do. I hope I wouldn’t have become bitter. I don’t know what would have happened if I had done something else.