Marie Mockett / photo credit: Rachel Eliza Griffiths

As a child attending antiques fairs and visiting galleries with her father, Marie Mutsuki Mockett soaked up the behind-the-scenes details of the latest fakery or debate over the authenticity of a piece of Japanese porcelain. The dealers presumed the little girl hovering around the edges couldn’t follow their highly technical verbal sparring. They couldn’t have been more wrong. Mockett explores that idea of access to another world – be it the antiques trade, or Paris or a Buddhist temple in the remote countryside of Japan – in her debut novel, Picking Bones From Ash (Graywolf, 2009).

The daughter of an American father and Japanese mother, Mockett saw firsthand the opportunities and constraints of moving between languages and cultures. Her keen attention to the details of cross-cultural experience comes through vividly in Picking Bones From Ash. The novel’s two main characters, Satomi and Rumi, must adapt to a wide array of geographical and social settings.

Picking Bones from Ash follows three generations of women. The book begins in 1954, with Satomi and her single mother running an izakaya, or pub, in the Japanese countryside. Through her mother’s belief in her ability, and constant supervision, Satomi becomes a piano virtuoso, leaving to study in Tokyo and, eventually, Paris. In Paris, Satomi begins a relationship with an American named Timothy Snowden, a charismatic young antiques dealer. Rumi appears in the second part of the book, decades after Satomi’s story has left off, and the reader soon learns that Rumi is Satomi’s daughter. Mockett fills in the missing pieces of the puzzle through the voices of the two women, in a story that encompasses ghosts, old secrets and the need to understand the past. The novel is set in Japan, San Francisco and Paris and touches on ideas of travel, ambition, and what it means to be a stranger in a strange land.

Marie Mutsuki Mockett’s short stories have appeared in many publications, including LIT, Epoch, Phoebe and North Dakota Quarterly. Her 2008 essay, “Letter from a Japanese Crematorium” won a distinguished essay citation in Best American Essays and was anthologized in The Best Creative NonFiction (vol. 3). She recently published an essay in The Morning News on the allure of flirting via avatar in the video game Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic.

This interview was conducted in person on May 6, 2010, at Mockett’s Jackson Heights home, with her young son, Ewan, in attendance.

Interview

LEE THOMAS: You studied East Asian Languages and Culture at Columbia. What was the path from finishing that degree to becoming a writer?

MARIE MUTSUKI MOCKETT: I always wanted to be a writer, it was a really early ambition, and for some reason I didn’t want to study literature or writing in university. I occasionally started to take an English class at Columbia, and just could never finish it. I think I wanted reading to be my own thing. I was attracted to studying Asian languages and cultures, and so I did. But all the time, I was working on different books. In high school I had been working on my fantasy trilogy, I had my big map and flow-chart of who was related to whom. Then I got to college and thought, ‘OK, I can’t really write that anymore,’ and was going to write a novel about Fisherman’s Wharf and Monterey, very John Steinbeck-like, which I continued to work on after college.

You were recently at Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and I also noticed grant acknowledgment from a variety of sources on the copyright page of your book – the National Endowment for the Arts, Target, the Minnesota State Arts Board and others. How did tho se organizations help you?

Those [grants] are procured by Graywolf, which is a nonprofit publisher. I think that’s just how they chose to distribute the money that they received. It may have been that those grants went more generally to Graywolf, and they chose to put some of the funds toward my book. Graywolf is just a different publishing model.

How did you link up with Graywolf?

How did you link up with Graywolf?

My agent submitted [Picking Bones From Ash] to them. He thought that Fiona McCrae would like my book, and that she would be a good editor for the book, and that Graywolf was a really good place for a first novel, which I think is true. It’s a great place. But I think it’s probably a great place at any stage of a writer’s career. I think they’re probably one of the few places left that actually wants to nurture the writer and thinks of writing as art and as something that takes a long time. It’s interesting because I think in the last couple years, you’ve had writers like me, who have started at Graywolf, but then you have people who have left larger houses to seek refuge at Graywolf. People go there for a lot of different reasons, but it’s always the same thing – they care about writers and artists and are very devoted.

Did you make a conscious decision to skip an MFA?

For a while, every year, I would think about applying. I didn’t say, “I’m just not going to do it.” I think I really didn’t want to, if I really had a burning desire to [I would have gone]. There are times when I think if I had gotten an MFA, maybe I would have worked more quickly or would have had a more sophisticated understanding of … everything. The one place that I always thought I might like to apply to was the Warren Wilson program, because most of writing is being by yourself with a computer. In general I just felt very protective of what I was doing, and my development, and wanted to be able to ask for help when I felt I needed it. I had a purist, idealist, unrealistic idea of what it was to be a writer and an artist. Me, up against a blank piece of paper, doing what I wanted to do, how I wanted to do it.

In your novel sacred objects have a lot of meaning. How do you feel like the material culture of American and Japan influenced your storytelling?

Mazarin Chest (detail) Victoria & Albert Museum

I think most people when they think of Japan, even if they’ve never been there, think of it as a really beautiful place, which it is. [Japan] has a really highly developed aesthetic, and their high arts are very, very high. I had a lot of exposure to that growing up, and it gave me a sense of Japanese culture at its most developed. My eighth grade term paper was on Japanese lacquer and I took pictures of my father’s collection and stuck them inside my term paper. So some of that is just based on what I was raised with and what I knew about Japan. But any fine art is connected to other things within a culture. In college I learned to look at an object and not just think about what made it beautiful, but also to think about the story behind it and what other significance it would have had in the context that it lived in. I think if someone is naturally interested in storytelling then you automatically want to know what the story is behind a thing. For example, any

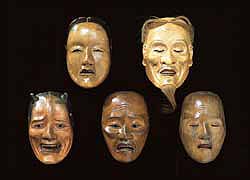

Noh Masks, Horniman Museum

study of Japanese ghost stories – and originally what I wanted was to write a pure ghost story – has to begin with a discussion about Buddhism, and you can’t really talk about ghosts and Buddhism without talking about Noh plays, and from there you get into masks, and you get into kimonos and you get into the other objects surrounding this very high art. So they all sort of fit together.

Language plays a really interesting role in the novel. Characters have varied linguistic abilities in Japanese, French and English. How do you feel like those questions of translation and understanding play out in the conversations characters are able to have? You speak English and Japanese – German too?

German was my first language, but my French is better than my German at this point. I’ve been on the inside of different languages, and in situations where I’m not expected to understand what’s happening, but I do. Watching my mother, who is incredibly fluid and articulate and nimble in Japanese, really struggle in English –something that I was aware of from childhood – has made me aware of what can happen when you can speak a language and when you can’t. You’re right, there’s the whole part in Paris where Satomi doesn’t speak French particularly well, or doesn’t have confidence, and then gains confidence and people wonder how she managed to learn French. These are things that happen when you travel overseas, and have to struggle with another language. This is the thing about being a foreigner, if you go to Japan and speak any Japanese, people are shocked, like you’ve managed to accomplish the impossible. I’m very aware of how physically in place and out of place people look. There are so many things that we are constantly telegraphing that put us in a particular culture that we’re not aware of. Having been aware of that for much of my life, I wanted to write about it.

Your level of fluency, I would imagine, constrains the idea of yourself when you’re in a different language.

I think it definitely changes who you get to be or how you’re perceived as you go from culture to culture.

Do you feel different in, say, English versus Japanese?

Sure. My husband and I were talking about this last night, because he’s European, he’s from Scotland. And I said, “You realize there are plenty of Americans who will tell you that there’s something about me that doesn’t seem completely American.” And he said, “Well, yes, I can see that.” But if I go to the U.K., I feel very American. And language is, of course, more than just speaking a tongue, it’s also picking up on humor. I was watching Glee with my mother and she can’t get half of the references. It takes a very high level, not just of language skill, but of cultural understanding to get half of what’s being said on that show. And then there’s the physical vocabulary that you have when you travel. I feel when I’m in Japan much more aware of my personal space. I’ve also been in situations with friends, I almost said foreigners, but I mean Westerners who are in Japan, and they don’t notice that they’re taking up a ton of room in the subway or train and they’re getting in the way or speaking loudly when it’s not appropriate. I’ve watched my mom move physically with a certain amount of freedom and confidence over here, and then in Japan look out of place because she’s been here for so many years. So, all these things make it hard if one wants to travel and have a sincere relationship. How do you know you’re really getting along with somebody? Just because you can shoot the breeze? Or because there’s something at your core that you’re really relating to. I think when you have an international relationship or marriage; it really demands that you figure that stuff out.

Picking Bones from Ash has three generations of very strong women and is told from two of their points of view. Did one of them speak to you first?

I always thought the story was supposed to be Rumi’s story, but Satomi was really bossy and gradually took over the novel. I know you hear writers say that, and I always thought that sounded sort of pretentious, and yet it’s really true. [Satomi] just had so much to say and she had strong opinions, and once she started talking I couldn’t stop her. There are some people that really love her – she’s independent and carved out her own space in the world. And there are other people who hate [Satomi], and think she’s not a nice person and, you know, she probably wouldn’t care.

When Satomi and Timothy Snowden visit Amsterdam, there’s a scene where she says that she’s “fallen into a storybook and was watching the characters come to life.” She goes on to say, “This is the difference between traveling to a foreign country and trying to live in one, as I was doing in Paris. Countries, like people, are at their most beautiful when you visit them briefly and allow them to enchant you over a short period of time.” I was wondering what you think the difference between that kind of pleasure and the pleasure of knowing a place intimately over time might be?

This is something I thought about a lot. One of my favorite books is The Sheltering Sky by Paul Bowles, and he talks about travelers, and who is a real traveler, and who is not a real traveler. I was born and raised in the United States, and so I have a strong connection to the landscape in different parts of this country, and I’ve been going to Japan since I was a child, so I have a pretty intimate and personal connection to Japan. My husband is from Scotland, and I’ve been going to the U.K. for the last 10 or 12 years now. The first time I went to the U. K. I was 17 and had won an essay contest and was awarded a trip. I went around and saw only the most beautiful things, and I came back raving about Europe and, like a lot of Americans who travel to Europe for the first time, had this idea that it was better. It didn’t matter what it was; it was just better. Now that I have a more personal connection, certainly to the U.K., it’s a more three-dimensional place. I have ongoing relationships with people there. The election is on today, and we’re wondering what’s going to happen with the election. I feel that when you really, really are connected to a place, you have harder and more interesting questions to ask, versus a quick trip, where what you see are the most beautiful things.

Do you think that there is value in knowing the flaws of a place?

Oh, sure. People say that if you go and live in Japan for a long period of time, people go through incredible waves of love and hate with Japan. It’s the most beautiful place, everything is efficient, they take care of their children and their families, the food is healthy, nobody’s fat, the trains run on time. On the other hand, with enough exposure, you also realize that [Japan] has incredible restrictions on certain human rights and civil liberties, and actually I don’t even think Japan is the worst offender, if you look at other parts of Asia. So for a naturally curious person, you would want to know the good and the bad. I think that you can’t be exposed to a place without learning what’s good or bad about it. There’s a very natural impulse, certainly when I was younger, to think that anything foreign was better. I think the world is more complex than that. I do think that for novels that are set in Asia, that are sometimes written by Westerners, a sort of classically historical novel, is in what I call the ‘beautiful Japan mode.’ I have a deep knowledge of Japan, and so I was trying to write a book from that point of view. [That project] was more challenging than I realized.

Oh, sure. People say that if you go and live in Japan for a long period of time, people go through incredible waves of love and hate with Japan. It’s the most beautiful place, everything is efficient, they take care of their children and their families, the food is healthy, nobody’s fat, the trains run on time. On the other hand, with enough exposure, you also realize that [Japan] has incredible restrictions on certain human rights and civil liberties, and actually I don’t even think Japan is the worst offender, if you look at other parts of Asia. So for a naturally curious person, you would want to know the good and the bad. I think that you can’t be exposed to a place without learning what’s good or bad about it. There’s a very natural impulse, certainly when I was younger, to think that anything foreign was better. I think the world is more complex than that. I do think that for novels that are set in Asia, that are sometimes written by Westerners, a sort of classically historical novel, is in what I call the ‘beautiful Japan mode.’ I have a deep knowledge of Japan, and so I was trying to write a book from that point of view. [That project] was more challenging than I realized.

It feels a little like being infatuated with somebody, versus being married to her. Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has said – I’m paraphrasing here – that to really love someone, you have to love even the bad and unappealing aspects of that individual. That real love is accepting, even appreciative, of a person’s flaws.

I think that’s probably true, as long as people aren’t getting hurt. There was a really funny article that I read a couple of years ago about how so many Japanese were going to France, and then France wasn’t what they thought. And so there was a Paris recovery course that they take, to get over the trauma of going to France and have it not be what they expected. Which, in a country that doesn’t really have a lot of mental health services compared to Western countries, I found really fascinating. A lot of people go to Japan and either find it a really alienating

experience, because they spent all their time in Tokyo and can’t understand what is going on and never go out into the country, and therefore decide that the country must be cold and precise and impersonal. I always wonder, how could you possibly know if it’s really and truly impersonal if you can’t understand a thing? Or people go and simply rave about it and decide that it’s a completely superior way of living. The thing is, I’ve gone through both extremes. But I think that’s a function of traveling. It’s funny how much thinking you have to do about foreigners and living in a foreign place if you want to have a smooth experience. I definitely thought about all of these things as I was writing this book, and I thought it was important and I thought it was true. It may not be necessarily pretty. There are a lot of readers who love the first chapter of the novel, which is set in a very historical, beautiful, pretty Japan, and then don’t like that complications arise. Yet, I feel that that is the truth of the experience.

The landscape, both in the opening chapter and then later on when they’re at the temple where Masayoshi is a priest, is magical. Are there places from childhood, or now, that you find to be magical?

Absolutely. You know, I’m a writer, so while I’m sitting here going on and on about “What is the truth of the experience?” I’m also a terrible romantic. I’m very susceptible to a beautiful, atmospheric place and I get very enthusiastic about these things, since I’m a Northern Californian. Japan is very beautiful. They know it, and they take very, very good care of a number of their most beautiful locations and make them even more beautiful. For me that’s just nothing short of magical. But I feel that way about places in the States too. I was in Japan two years ago for the cherry blossoms, and everybody goes on and on about the cherry blossoms in Japan, but it really was the most beautiful, ecstatic experience. It’s spring, so it’s warm, and there are cherry trees as far as the eye can see because they’re indigenous. You could be on a bullet train going from city to city and there are cherry trees beside the bank of a river, and in the town and then all the way up the

hillside until they disappear. In Kyoto there are these night walks where the trees are lit-up by theater people, so they glow, and everybody’s drunk and you’re climbing higher and higher up a hillside, past cherry trees, and these lit-up temples. We did one of these walks to the Kiyomizu Temple, which is surrounded by cherry trees, and the temple is on a cliff, so it looks like it is floating on this cloud of cherry trees, and it’s lit so that it looks that way. It’s just incredible.

Parenthood is central in Picking Bones from Ash, especially the tension between desire and discipline. Satomi and then Rumi almost get swallowed up in parental desire for them to be gifted in a particular way. How do you view the pull between a parent wanting his child to play the piano or learn about Japanese antiquities, and the child maturing and eventually wanting to break with her parents?

You look at someone like Tiger Woods or Beyonce, did they want to be doing what they’re doing? Do they know? There are an awful lot of arts that require training from a very early age. You look at the amazing Soviet gymnasts back in

the eighties, chosen at a small age, and the family was given an apartment from the government because their child was talented. It sounded so atrocious to us because we believe in freedom, and yet excellence in something, certainly like a musical instrument or dance or gymnastics, requires incredible training from the time you’re really small. That’s the tradeoff. It’s sort of the dirty secret that nobody wants to talk about. I also think that people are always capable of so much more than they think, they just have to ask it of themselves. “Should you or should you not?” I don’t really have the answer to that.

Has becoming a parent yourself changed anything for you as a writer?

I don’t know. We’re still finding that out. Part of what I was thinking about when I wrote this book was the number of people I know who are writers or want to be writers or artists, who do not want to have children because they think it’s going to get in the way of an artistic career. This is one of these subtle questions. Once you have a child there’s the whole stay-at-home mom versus working mom debate, and also the women writers who have children and don’t have children debate. I was thinking of people who really feel very strongly [about this]. Somebody once said to me that for every child a poet has, two books of poetry don’t get written. Men don’t have the same kind of pressure on them because they have wives who will take care of the children, but it’s different for female artists. So Satomi has a point, if she’s going to be this great, talented person, she can’t be putting all of her energy into a child, if she doesn’t have any support to help raise the child.

François, in a conversation that he’s having with Rumi, says, “Remember, the most important thing in life is to be able to see things as they really are.” The idea of truth, and not only what is true, but does the truth matter, and what part of the truth matters, drives many of the characters. For both children and parents, there is that sense of wanting to know.

I think that that’s true. Of course when you’re a child, you parents seem to know everything and have all the power, and then you discover that they’re just human, they’re not gods. Then you yourself become a parent and you realize that your parents were just doing the best they could, in most cases, just as I’m sort of basically doing the best I can here. The search for truth is something that is very important to me, and I wanted to write about it in a way that wasn’t too heavy-handed. That’s a very Buddhist idea, to try to see truth through illusion.

Do you think there’s a difference between the way that Buddhism and Shinto perceive truth?

Well, Buddhism is very focused on the truth, seeing truth and having insight, and not being confused by illusion, and as a result is considered much more of a philosophy or a philosophical religion. Whereas Shintoism is concerned primarily with purity, and in many ways morality doesn’t come into play into Shinto. It’s such an old and animistic religion. It’s not monotheistic, and it’s not trying to regulate behavior in the same way that we think of religion regulating behavior. It comes from a much more chaotic universe with many more gods and demons, and even the gods themselves may not be particularly kind.

I do think it’s very old world to be very integrated into your family, and to accept the power structure of the family. It’s much more new world for us to forge out on our own and do things that are very different from our parents. With that comes a lot of wonderful freedom, to redefine ourselves or be truer to some sort of inner nature that we might have. That could mean that we lose our family ties, but that could also mean that you see through the illusion that your parents have cast over your life. In my novel we have characters that needed to move out beyond their family and parents, but at the end of the book also have to be able to come to terms with their parents. I think that’s a very modern struggle.

As with most things, there’s a dark side to that freedom, there are certain trade-offs to that lack of structure?

Absolutely. Now that I have a child, I’m thinking of all the really wonderful things about Japan and that Japanese culture has to offer that celebrate childhood. The reason there’s this fish mobile rotating from the ceiling is because yesterday was Children’s Day and the traditional decoration are these huge Carp streamers, and somebody sent us this mini-mobile for Ewan. We went to a Children’s Day event at Japan Society and made origami helmets. Tradition is wonderful and grounding, and its there for you, and people have contemplated really hard, existential questions for centuries and often in tradition you can find some insight and answers. But that doesn’t mean that it’s going to meet every single modern problem. If only living were that easy, that all the

Isabella Bird

answers are actually there. They’re really not, but you can still find a lot of insight. I guess that was why I was trying to put in this Buddhist temple, and put in this priest, because I do think there’s a lot of value [in tradition]. But I’m not a conservative who thinks that we should all live the way that people always have, it’s just not possible. I love change and technology and travel; those are very modern things. Mass, popular travel was [reserved for] these people like Isabella Bird who got to go to foreign countries and write books and send them back for the masses to read. It just doesn’t work that way now.

People’s only exposure to Europe or Asia or Africa was often through reading.

Right. And the odd exotic specimen, Pocahontas going off to England, and suddenly there’s a Native American on display. It’s really hard to imagine what it was like. You think about how, even now, we’re shocked and startled when we meet a foreigner, it would just be even worse and more intense [back then]. My family has a wheat farm in Nebraska, and I go in the summers and I’m the most ethnic person around. I realize I look very out of place.

Travel is threatening though. This weekend I went to a Japanese restaurant that we love in New York, and we met a Japanese family there. They had come for a three-day shopping trip, and of course, there they were eating in a Japanese restaurant. Which is sort of like Americans going to Japan and then eating at  McDonalds. Travel’s hard. If you really engage in it in an authentic way, which, again, is why I love The Sheltering Sky, it’s challenging. It’s existentially challenging. I think you can step into a foreign country and it doesn’t quite feel real. They’re all just pretending to go to work. They aren’t really watering geraniums in their window boxes. They just put those out to make it look like it’s a storybook place. But, no, places are real.

McDonalds. Travel’s hard. If you really engage in it in an authentic way, which, again, is why I love The Sheltering Sky, it’s challenging. It’s existentially challenging. I think you can step into a foreign country and it doesn’t quite feel real. They’re all just pretending to go to work. They aren’t really watering geraniums in their window boxes. They just put those out to make it look like it’s a storybook place. But, no, places are real.

You just went to Kansas City and met with people who had read your book as part of the book club for the Kansas City Library. What is it like to meet your readers?

Mostly it’s just really cool. I obviously loved to read before I knew I wanted to be a writer, so in an ideal world people are reading my book and thinking about things and, I hope, enjoying it. But of course a writer spends an awful lot of time on her own constructing a story, not interacting with people, so there’s an element of unreality about meeting people who have actually read the book. For me it just reminded me of that early love of books, that pure love for books that I had, before I was embroiled in the process of the agent, and publishing and reviews and all of that. So, it really was just an extremely pleasurable experience and a reminder of what the whole thing was all about in the first place.

The debut novelist space feels very, very crowded. There are books that get a lot of attention early on, books that grow slowly, books that fall through the cracks, and books that maybe shouldn’t have been published in the first place. You’re aware of all these things once your book has been published, and aware that everybody else who has published a novel is aware of these same tensions. It’s so hard to get into this group of debut novelists, and then you’re in and it feels crowded, and so to have an experience where I just get to talk about the book is really nice.

Have you been surprised at all by readers’ reactions to anything in the book?

I guess I feel more interested and curious than I do surprised. Once the book is done, it’s out there – it’s everybody else’s book. As a reader, I’m aware of the fact that how I read isn’t the way that everybody else is going to read a book. So I know that the way that people will read the book will be different, or they may pick up something that I hadn’t intended. I guess I don’t have an illusion that I have any kind of perfect control over the entire experience from here on out. I do the best job I can so the book feels right, and then it’s up to other people to respond to it. It’s flattering, actually, if people pick up on different aspects of the book. I was surprised by how feminists embraced the book early on, because I wasn’t thinking about feminism.

What are you working on now?

I have about 60 pages of a novel in progress that will again be about a specially talented girl, and will examine the intersection of spirituality and modernity. I’m also working on a few short articles, but am trying not to talk too much about them so I don’t jinx them. But I will say this: I’m leaving for Japan soon, hoping to get some research done. Prior to writing the Crematorium article, I didn’t know I could write nonfiction. But that piece was so successful, I feel eager to try my hand at writing some more pieces on the Japan I know, that others might not see or hear about in the mainstream or weirdness-seeking news.

You recently found out that you were shortlisted for the Saroyan International Prize. Congratulations. You wrote on your blog,

You know, it’s a funny thing. At one point, every writer works and works and works in isolation, knowing almost no one. That writer might, say, go to a conference, not really knowing why she’s there, but watching all these published authors on the other side of some “fence,” talking about the publications, and wondering how she ever gets to part of that world. And she might feel that her career is going nowhere, while all that time, her work is actually “working” for her.

What would you say to that writer?

You just have to keep working. You really do have to fight, and keep writing, and keep submitting, and doing the best work that you can. Assuming your work is of a high level, you just have to keep sending it out, and you never know what kind of an opportunity will arise from something that you’ve published. One thing can completely change a career. I’m somebody who was afraid to submit. It’s not an uncommon problem. And I still find it hard, and I still go through phases where I just can’t. Most of the time, I think, it’s better to put yourself out there, because then you have a chance of something coming back. But if [writing] is something that you really, really want to do then you have to keep fighting, and keep working. Eventually something will happen, it just will if you’re good. It’s very difficult. The industry is at a really interesting point right now. I kind of struck the jackpot, getting to publish with Graywolf. They’re a small press, but they’re a really great small press. Paul Harding [published by Graywolf] just won the Pulitzer. It’s a chaotic time in the industry, which can be depressing, but there’s opportunity within chaos. My father always used to say to me, “Look, people do it. People become published authors. They become part of that world. Why wouldn’t it be you?” It’s not magic. It’s just a lot of work.

You just have to keep working. You really do have to fight, and keep writing, and keep submitting, and doing the best work that you can. Assuming your work is of a high level, you just have to keep sending it out, and you never know what kind of an opportunity will arise from something that you’ve published. One thing can completely change a career. I’m somebody who was afraid to submit. It’s not an uncommon problem. And I still find it hard, and I still go through phases where I just can’t. Most of the time, I think, it’s better to put yourself out there, because then you have a chance of something coming back. But if [writing] is something that you really, really want to do then you have to keep fighting, and keep working. Eventually something will happen, it just will if you’re good. It’s very difficult. The industry is at a really interesting point right now. I kind of struck the jackpot, getting to publish with Graywolf. They’re a small press, but they’re a really great small press. Paul Harding [published by Graywolf] just won the Pulitzer. It’s a chaotic time in the industry, which can be depressing, but there’s opportunity within chaos. My father always used to say to me, “Look, people do it. People become published authors. They become part of that world. Why wouldn’t it be you?” It’s not magic. It’s just a lot of work.