There has been much hullabaloo. Is the MFA system killing American fiction, or is it bolstering it? Is the short story a dead form, or is it seeing a renaissance? Is the novel becoming a minority cult, or is it headed in exciting new directions? Should we give up on fiction altogether and dive headlong into nonfiction, or is the market’s demand for nonfiction putting the kibosh on what could have been perfectly good novels? Is print dead completely, or are ebooks a false apocalypse? Is the sky falling, or are we just marching ever closer to the sublime? It’s enough to make you walk away from your desk in search of the nearest pint.

The writers who stick to their keyboards don’t seem to care much at all about such questions outside of how they impact them in practical and financial concerns. I had the opportunity to talk with two such writers, Elif Batuman and Geoff Dyer, recently at the Cúirt International Festival of Literature.

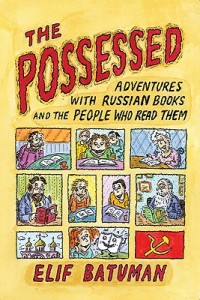

Batuman’s first book, The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them, published to much acclaim last year in the states and recently out in the UK from Granta, is a collection of reportage on Batuman’s time as a PhD student knee-deep in Russian literature, graduate school, and academic conferences. A gloss like that makes the book sound dry, but in truth, it’s as grabbing and compelling as the best fiction, and funny to boot. In fact, during Q&A she admitted that for literary and extra-literary reasons she wanted to sell the book as a novel, but her agent wouldn’t have it.

Batuman’s first book, The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them, published to much acclaim last year in the states and recently out in the UK from Granta, is a collection of reportage on Batuman’s time as a PhD student knee-deep in Russian literature, graduate school, and academic conferences. A gloss like that makes the book sound dry, but in truth, it’s as grabbing and compelling as the best fiction, and funny to boot. In fact, during Q&A she admitted that for literary and extra-literary reasons she wanted to sell the book as a novel, but her agent wouldn’t have it.

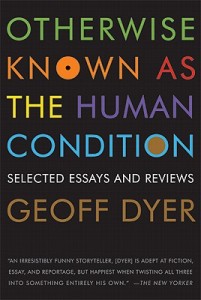

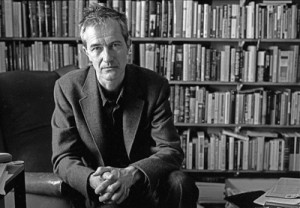

Dyer’s published numerous acclaimed books and was at the festival to promote his latest collection of essays and reviews, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition. Praised far and wide for a brave and flippant attitude toward genre boundaries and his broad range of subject matter (from photography to art to couture to, soon, film), Dyer read from a section of Out of Sheer Rage—regarding his youthful disdain for all things academic—before reading from his latest. At one point during Q&A, an audience member boldly declared that he considered Dyer’s most recent novel, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, to be no more than two half-thought-out novellas, and that the latter of the two was superior to the first due to what he considered a more faithful representation of Varanasi. Dyer responded with a passionate diatribe on why the two sections belonged together—in fact leaned on each other for support—and mocked the critics who point out this split structure as some kind of fault, or that the reason the love interest in the first half of the novel disappears in the second was that Dyer forgot about her. There was much clapping. As I heard the sound man comment on the way out, ragging on academics and critics in Galway always gets applause.

Dyer’s published numerous acclaimed books and was at the festival to promote his latest collection of essays and reviews, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition. Praised far and wide for a brave and flippant attitude toward genre boundaries and his broad range of subject matter (from photography to art to couture to, soon, film), Dyer read from a section of Out of Sheer Rage—regarding his youthful disdain for all things academic—before reading from his latest. At one point during Q&A, an audience member boldly declared that he considered Dyer’s most recent novel, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, to be no more than two half-thought-out novellas, and that the latter of the two was superior to the first due to what he considered a more faithful representation of Varanasi. Dyer responded with a passionate diatribe on why the two sections belonged together—in fact leaned on each other for support—and mocked the critics who point out this split structure as some kind of fault, or that the reason the love interest in the first half of the novel disappears in the second was that Dyer forgot about her. There was much clapping. As I heard the sound man comment on the way out, ragging on academics and critics in Galway always gets applause.

Although what they were most looking forward to was post-festival naps before post-festival drinks (when in Galway), Elif and Geoff were kind enough to sit down with me to appreciate but dismantle the working thesis I had of Geoff’s novel, answer a few of my questions, and talk between themselves.

Shawn Mitchell: I read The Possessed and Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi back to back and noticed a lot of parallels between them. In several ways, Dyer’s novel reads like an illustration of a lot of what is discussed in The Possessed, like when Batuman talks about protagonists trying to make their lives as meaningful as their favorite books, and Dyer quotes other authors on Venice and Varanasi openly throughout the novel. Or how Batuman describes the structure of Saint Augustine’s Confessions: the first half is an account of Augustine’s youth, going to the theater, his love affairs, while the second half is a denunciation of that time and the idea of narrative itself and moves over to exegesis and philosophy. Dyer’s novel moves in the same way, with the first half following a love affair and the second a spiritual awakening. Dyer, were you thinking of Confessions when you structured this? Did you have any other models?

Geoff Dyer: I like the point, but it seems to me there’s almost an invariable rule at work here. Whenever somebody says to you “A-ha! Behind your book was this book,” it’s always the case that you’ve not read it, even though that seems a peculiarly close fit. I’m sort of happy with your summing up of what’s going on in those two parts, especially since part one of my book is so hedonistic and carnal in all sorts of obvious ways and in part two we get this kind of renunciation or just a fading away of the carnal and hedonistic and the self. That is exactly what is going on, but unfortunately, for your thesis, I’ve not read it.

Elif Batuman: You don’t have to have read it to be aware of it. You could still have a conversion structure even if you haven’t read it.

Dyer: Yes, but that wasn’t at the front of my consciousness. At the front was Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, obviously, and also a book Elif and I were talking about earlier, American Purgatorio by John Haskell. I loved the fading away of the character in that. It’s really a work of genius, and I liked the journey he underwent. There was another book that we talked about, a book that begins in Venice and if I’m remembering correctly goes by India in an incredibly trippy way, Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb, written in the ’30s in Hungarian. It’s this mind-blowingly psychedelic journey that the guy goes on from ostensibly quite straightforward realist beginnings.

Both of you write a lot of nonfiction about other subjects, arts, and sports and such. Elif, in The Possessed you mention “la sindrome di Stendhal,” where viewing a beautiful or expansive work of art brings on dizziness, fainting, and hallucinations. I’ve more or less done everything you jokingly suggest to not do in your book. I moved to Brooklyn and did the broke and decadent thing while working in publishing, and now I’m writing short stories in an MFA program. One problem I’ve noticed now is that it’s hard for me to get into fiction without picking it apart for craft. Do you both find that you’re able to engage with what you read in the same way that you did when you were young? Do you still suffer from Stendhal Syndrome from time to time?

Batuman: With works of art? Yes. There’s a risk of it getting kind of excessively meta. A lot of my book was obsession with obsession. This whole fall I was working on two pieces at the same time. One was about Dante-mania in Florence and the other was about football hooliganism in Istanbul, and I realized at a certain point that it’s the same story, that people who are obsessed with Dante are exactly the same as people obsessed with football, and it doesn’t really matter what you’re obsessed with. So I’m personally trying to move away from that. I find that I’m not as moved by art as I used to be ten years ago. I hope that it’s not a permanent thing, but it might be. I know a lot of people who did PhDs in literature who say it’s impossible now for them to read. You wrote a nice thing about that, Geoff. You had a very nice explanation for why you don’t read much anymore, because when you read when you were young, everything that you read was a much larger percentage of the total that you’d read and the total of your formation. I think that’s really true. What am I going to read that’s going to totally rock my world? It happens every now and then. I’m trying to get myself to a point where it happens more than it used to.

Dyer: To go back to that, that’s in an essay called “Reader’s Block.” It’s crazy, it’s madness to suffer from it, but one does periodically. It gets gradually better—one is in remission quite a lot, but yes, of course when you’re reading when you’re eighteen, nineteen, your judgment is not so refined. I would go along with David Shields’ argument in Reality Hunger to a certain extent, but I think he should emphasize more that it’s not necessarily the novel that’s the problem so much as just one’s own approach. In terms of one’s ability to respond to works of art—meaning music, literature, everything—I don’t find that diminishing at all, actually.

Last night we were listening to Beethoven really seriously, and that is an incredibly deep experience. Christian Marclay’s film, The Clock, is one of the greatest works of art, I think, of the last twenty years. In terms of one’s ability to respond, for me I’ve always believed I have a completely anti-addictive personality. The obsessive and the addictive are two quite contrary conditions. I think I’m a total obsessive and that’s why I don’t have an addictive tendency. You’re obsessed, obsessed, obsessed about something and then you’re obsessed about something else. That’s why I’ve tended to be obsessed with different things as opposed to constantly plowing one particular furrow.

Batuman: That’s interesting. No, I know some people who are just barking up the same tree their whole lives pretty obsessively.

Dyer: At that point they’ve become addictive, not obsessive.

Batuman: I see.

Dyer: I suppose obsessiveness can become a problem. Part of the problem of feeling there’s nothing to read is because one is defining what is there to be read too narrowly, because of course there’s loads of stuff that’s great to read outside the realm of fiction or novels. It really is inexhaustible, I think. History, anything, whatever you want to read.

Elif, in an N+1 essay back in 2006, you examined the state of the short story. I read that essay with a sort of sad recognition as an MFA student. I was trying to think, though, if I noticed those trends you mentioned, such as everyone having proper names and the hyper-specificity of objects and the abuse of in medias res, in BASS 2010. Have you revisited short stories at all more recently?

Elif, in an N+1 essay back in 2006, you examined the state of the short story. I read that essay with a sort of sad recognition as an MFA student. I was trying to think, though, if I noticed those trends you mentioned, such as everyone having proper names and the hyper-specificity of objects and the abuse of in medias res, in BASS 2010. Have you revisited short stories at all more recently?

Batuman: No, it was awhile ago and I think it’s changed and that MFA programs have gotten a lot more diverse since then. When I wrote that, I read the BASS 2003 and 2004 and I had only looked at MFA programs two years before that, so it’s been around ten years. There’s so much difference now that I don’t think it’s possible to generalize. The other thing I wrote about creative writing programs was a review of Mark McGurl’s book about the rise of program writing, which I did for the London Review of Books. In there I said a lot of stuff about the creative writing program, but I was really just responding to what McGurl said, and he’s my age, so I think he’s talking about the same time ten years ago. I don’t think any of that is reflective about the current state of affairs, about which I know very little.

Have you written any short stories, Dyer? I’ve mainly come across nonfiction and novels.

Dyer: I have written stories, it’s just that people haven’t tended to realize they were stories. To go back to a piece in that yoga book I mentioned. My girlfriend and I were coming back from the Bahamas and stopped off in Miami. I wrote something without any sense of what it was going to be, and then I wanted to sell it, so I sold it to the Observer in Britain as a travel story. OK, that’s fine. Then a little while later an anthology editor asked me if I had a piece, and I said “Oh, yeah, I’ve got this short story,” same thing, because I like to recycle, of course. So it was then published as a short story kind of thing. Then I sold it to the American journal The Threepenny Review, where they don’t have a travel section, and they published it as a memoir. Then as a result of it being published there, it was selected as one of the Best American Travel Essays, and then finally it’s reprinted in my yoga book under the title “The Despair of Art Deco.” Again, like a lot of the pieces in that book, it could equally be a short story, but that’s really not my concern at all. That’s all about the expectations that are brought to a certain type of writing, and people’s ideas about how a certain form of writing is supposed to happen. So, actually, I really believe in my case when people have said, in a similar way to the way the guy in the audience earlier, “Oh, this is no good,” actually what they mean is that it is not conforming to their generic expectations of how something is meant to behave, even though the piece I’m writing isn’t trying to do that. It’s so much this thing of generic expectations that I’m very happy to be at loggerheads with, or at least not to conform to those expectations.

Dyer: I have written stories, it’s just that people haven’t tended to realize they were stories. To go back to a piece in that yoga book I mentioned. My girlfriend and I were coming back from the Bahamas and stopped off in Miami. I wrote something without any sense of what it was going to be, and then I wanted to sell it, so I sold it to the Observer in Britain as a travel story. OK, that’s fine. Then a little while later an anthology editor asked me if I had a piece, and I said “Oh, yeah, I’ve got this short story,” same thing, because I like to recycle, of course. So it was then published as a short story kind of thing. Then I sold it to the American journal The Threepenny Review, where they don’t have a travel section, and they published it as a memoir. Then as a result of it being published there, it was selected as one of the Best American Travel Essays, and then finally it’s reprinted in my yoga book under the title “The Despair of Art Deco.” Again, like a lot of the pieces in that book, it could equally be a short story, but that’s really not my concern at all. That’s all about the expectations that are brought to a certain type of writing, and people’s ideas about how a certain form of writing is supposed to happen. So, actually, I really believe in my case when people have said, in a similar way to the way the guy in the audience earlier, “Oh, this is no good,” actually what they mean is that it is not conforming to their generic expectations of how something is meant to behave, even though the piece I’m writing isn’t trying to do that. It’s so much this thing of generic expectations that I’m very happy to be at loggerheads with, or at least not to conform to those expectations.

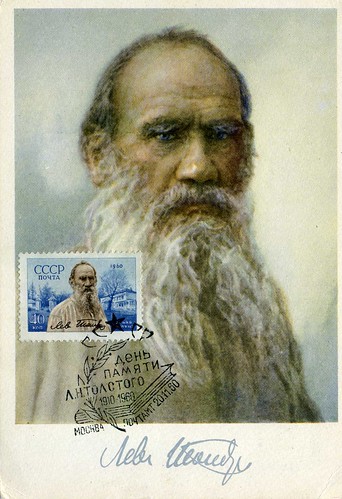

Batuman: The Tolstoy thing I originally wrote as a short story very cautiously. It was really about Chekhov, only about Tolstoy. But then I submitted it to Harper’s and they took it. I thought they were taking it as a short story, but they said they’d assigned me a fact checker. There were really only a few things that weren’t factually accurate, so I changed those and they ran it like that. I kind of struggled against it, but it became clear that they weren’t going to publish it if it wasn’t nonfiction.

Have you returned at all to fiction since you published this book? Do you picture returning to it in the future?

Batuman: No, I’m making ends meet. I was doing journalism because that’s what pays. I think like Geoff keeps saying, it seems like a really arbitrary distinction. I know what I want to write, but I don’t know if they’re going to make me call it nonfiction. I’m not going to become Henry James and invent some whole intrigue. The things I want to explore in the next book are all invariably something that have happened to me or things that I read, so in that sense it’s like the first book. But I want to do a book about sex, so I don’t want to have to present it as nonfiction, for obvious reasons.

Do you feel the mission you state at the beginning of the book, where you say you’re setting out to see if studying literature in a very academic way works as a way to learn to write, has worked?

Batuman: The thing that really had a big influence on me was literary history. I realized that a lot of what I thought about as theory was actually putting things in context, and that has been extremely important to me and all the other writing I’ve done, including journalism.

I think the standard idea now is that if you’re an English major, you go out and get an MFA if you want to be a writer.

Batuman: Right, or a PhD if you want to be an academic.

Or now you get a PhD in creative writing because there are so many people with MFAs that you have to distinguish yourself further. Dyer, did you study writing in college at all?

Dyer: Oh, no, I studied literature. That’s the, you know, “How did you become a writer?” question. The answer is by being a reader. I think a straight-down-the-line, old-fashioned, Beowulf-to-Beckett course remains the very best training to being a writer, even though unfortunately studying literature so often means studying criticism. That’s a shame, but it gives you a great sense of things. Back when I was young, there was only one course in England in creative writing, the UEA one. So I didn’t study writing, but I do think America has led the way in fiction since the second World War. It’s very difficult to come up with a strict causal explanation, but certainly it can’t be divorced from the way it’s been supported by creative writing programs.

Batuman: When you say led the way, do you mean in quantity or quality or money?

Dyer: Quantity and quality.

Batuman: You really think so?

Dyer: I think for somebody of my age, it was American writing that seemed so much more exciting, and, weirdly, so much more contemporary. People like Graham Greene seemed older than their American equivalents. It’s that weird demotic of the American voice that seems more modern. In Britain, the first person to really domesticate that voltage was Martin Amis. For me, America really has led the way and set the standard in postwar fiction.

That’s nice to hear. Usually I just hear people slagging on America and Americans over here. So your next book is going to be fiction, Elif?

Batuman: Yes, I would rather have it appear in the world under the guise of fiction. All the scandals lately make it very obvious why it’s bad to write a fictional book and call it nonfiction, to say it’s a memoir when you’ve invented it. It’s a very recent thing where you’re not able to write nonfiction and call it fiction. I don’t see the ethical or legal or artistic problem with it. I think if Proust were to write now, they would make him make it nonfiction, it’d have a colon in the title, it’d be In Search of Lost Time: The Rememberer’s Journey. I want to do the book I want to do and I would rather call it fiction for extra-literary reasons, but whatever.

And Dyer, what’s your latest obsession?

And Dyer, what’s your latest obsession?

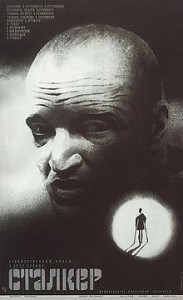

Dyer: I was meant to be writing a book about tennis, but I’ve ended up writing a very very detailed summary of Andre Tarkovsky’s Stalker.

Batuman: How did you get into that?

Dyer: I’ve always liked that film. It’s always haunted me. I found I was just enjoying summarizing the film in a really mad way.

Batuman: That’s awesome.

Dyer: And because Tarkovsky is this ultimate figure, talked about in such reverential terms.

Batuman: Right, “unsummarizable.”

Dyer: Right, I just felt there was a way to talk about Tarkovsky with a kind of lightness, and I was enjoying that. I also felt that since people are always commenting on how I’ve written books about jazz, photography, and everything else, it was about time to add cinema to my CV. Then of course cinema is such a part of everyone’s autobiography, and this was a way of talking about the state of cinema, so it ends up being much more. Because of the nature of the film, it lends itself very well to a very precise summary and also all sorts of loopy speculations as well.

Batuman: Sounds amazing. When does that come out?

Dyer: February 2012, and now I will drum up a blurb in the name of Elif Batuman, and if I don’t hear back from you in twenty-four hours, I’ll assume you’re cool with it.

Further Links and Resources

Elif Batuman

- Visit Elif Batuman’s website. She blogs at My Life and Thoughts.

- Geoff Dyer’s website contains more information about his thirteen existing books and his fourteenth, out next year.

- Listen to the New Yorker‘s podcast from March 7, 2011, with Elif. She discusses her article on Turkish soccer fans. (No subscription necessary to listen.)

- Also in the New Yorker this spring, Geoff Dyer’s piece about land art, including Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. (Subscribers can read this online.)

- Pick up a copy of The Possessed or one of Geoff Dyer’s books from your local indie bookseller.

Geoff Dyer, courtesy the author's website