It is impossible to say how the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night.

– Edgar Allen Poe, “The Tell-Tale Heart”

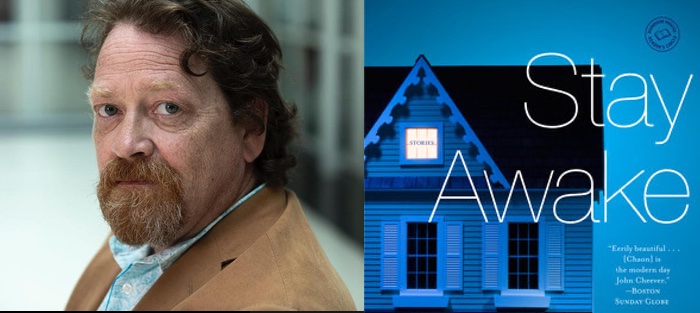

In the months leading up to our daughter’s birth, I had a basic worry. It was the most common and primordial of parental fears, that I might not be good enough, or patient enough, or loving enough, that I might not bond with her or might resent her for the reallocation of time. The short story “The Bees,” by Dan Chaon, drew me to it during that plague winter of 2020 and draws me back to it in the spring of Zelda’s second year, because it’s that fear refined to its purest form. It’s a classic horror story in the tradition of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” an expert distillery of all things parental terror that invokes dread through foreshadowing, a creeping progression of memories, and a relentless repetition coupled with a fundamental uncertainty that holds the reader in the same stiflingly anxious atmosphere as its main character.

“The Bees” follows Gene, an allegedly recovered alcoholic and UPS deliveryman who lives in the Cleveland suburbs with his wife, Karen, and their five-year-old son, Frankie. Frankie has been inexplicably waking up screaming every night and not remembering it afterwards—a nightmare scenario, to be ripped awake by your child and not be able to help them in any lasting way. My partner, a family medicine physician, informs me that these sound like common night terrors, but in the story, they are unnamed, and in such have a nameless power.

Over the course of the story, however—spoilers, ahead—we learn that Gene has or had a previous wife and son, whom he emotionally and physically abused before abandoning them and almost dying in a drunk driving accident. Since then, he hasn’t been able to locate them, hasn’t sent child support, and hasn’t told his new wife about his previous family. The tale is set when Gene’s past has come “full circle,” when he’s come to the point with Karen and Frankie when his life with Mandy and DJ ended a decade prior. “Something awful has been looking for him a long time,” Gene thinks, and that something culminates in the story’s awful ending, when Karen and Frankie die in a house fire.

This vulture’s-eye-view of the story is bad enough on its own, but it’s Chaon’s craft that gives it its carrion stink. We all know about Chekhov’s gun and its rules, and here we have screams and smoke and the “trembly, pressure-cooker hiss” of a cicada—so many loaded narrative weapons casting long shadows forward. The very first sentence, “Gene’s son Frankie wakes up screaming,” is unfathomably sad when you revisit it in the ticking red emergency light of the story’s final words:

They place the corpse into the spread, zippered plastic opening of the body bag, and he can see the mouth, frozen, calcified, into an oval. A scream.

If that’s not enough to alarm you, there’s also the images that Frankie’s screams conjure in Gene’s mind, of a child falling or being caught in machinery or mauled. And the horror-story-taboo moment in their past when Karen told Gene she didn’t believe anything bad could happen to her, and the ambulance’s siren in the distance the evening of the fire. Even a throwaway line from the pediatrician, who says a disturbance like the screams usually “simply passes away,” foreshadows the ending, giving it an oily, noxious sheen of inevitability.

Chaon builds on this sense of looming death through a constant accrual of memories that, as they gather and return and congeal, seem to manifest themselves in the suggested presence of Gene’s former son. Early on, we learn only that Gene used to be a “drunk” and a “monster,” but as the story continues, these abstractions transform into a memory of him throwing beer bottles the night he left. “He’d been drinking a little” becomes “he slapped her hard enough to knock her out of her chair” and DJ’s eye “swollen shut and puffy.” And while these memories materialize, so does DJ. First, he’s a child in Gene’s dream, then he seems to be Frankie’s imaginary playmate, followed by the voice on the other end of a phone call Karen recieves, until, finally, he’s an adult in another dream, saying “I know how to hurt you.” DJ is an “observant, unfriendly presence” throughout the story, never literally there but drawing ever nearer as Chaon ratchets up the pressure until Gene, his family, and the reader are “at the mercy of his fears.”

There’s a kind of rhyming lyricism to Chaon’s horror, an artfulness to how he repeats words and images over and over for a circling effect that mirrors the outing of the truth and the revisiting of the father’s sins upon his undeserving, undeserved wife and son. Again and again things circle, like the plate that “clatters in a circling echo” after Gene pounds the table. Again and again there’s the static and the droning buzz, a kind of malevolent tinnitus. Three times Gene wakes up disoriented and unsure where he is as a woman-as-saint looks down. Twice he thinks himself a monster. Twice a child is thirsty, and once Gene drinks straight from the carton, guzzling milk as if he can douse the disappointment emanating off Karen “like waves of heat” and the “smothering, airless feeling of being watched” as his behavior becomes increasingly erratic. Chaon’s most artful linkage occurs when Gene’s past is connected to insects (“all the things that he doesn’t quite remember are circling and alighting, vibrating their cellophane wings insistently”) and insects to the fire (which sounds like “the amplified sound of tiny creatures eating”), so that, imagistically at least, the fire is linked to his past. These grim echoes, Chaon’s dark calls and responses, are a rhythmic drumbeat driving us into those insect flames.

There’s a kind of rhyming lyricism to Chaon’s horror, an artfulness to how he repeats words and images over and over for a circling effect that mirrors the outing of the truth and the revisiting of the father’s sins upon his undeserving, undeserved wife and son. Again and again things circle, like the plate that “clatters in a circling echo” after Gene pounds the table. Again and again there’s the static and the droning buzz, a kind of malevolent tinnitus. Three times Gene wakes up disoriented and unsure where he is as a woman-as-saint looks down. Twice he thinks himself a monster. Twice a child is thirsty, and once Gene drinks straight from the carton, guzzling milk as if he can douse the disappointment emanating off Karen “like waves of heat” and the “smothering, airless feeling of being watched” as his behavior becomes increasingly erratic. Chaon’s most artful linkage occurs when Gene’s past is connected to insects (“all the things that he doesn’t quite remember are circling and alighting, vibrating their cellophane wings insistently”) and insects to the fire (which sounds like “the amplified sound of tiny creatures eating”), so that, imagistically at least, the fire is linked to his past. These grim echoes, Chaon’s dark calls and responses, are a rhythmic drumbeat driving us into those insect flames.

At the same time, much of what we sense and feel in this story isn’t literally true. Frankie may remind Gene of DJ, but Frankie is not possessed, and there’s no way to know who was actually on the phone. Chaon instead does it all through subtext, which is actually more upsetting than if it actually were happening, because you can’t be sure what’s real and what’s only in Gene’s head. You can’t even know whether Gene is being truthful when he tells Karen he hasn’t been drinking again, or if his present is being blurred like his past was when the “alcohol grotesquely distorted his perceptions” and made him see DJ as a hateful presence.

“The more you know, the less sure you are of anything,” Karen says (in the kind of line that could define Chaon’s whole aesthetic), and you could almost read this story as a projection of Gene’s fears, a drunkard’s rationalization of the fire and a literalization of what his past would do to the present were it revealed, to burn his life to the ground. But I’ve never been one for stories where you’re made to wonder if it’s all just in the character’s miiiiind, man, so I prefer to take at least the abuse, fire, and death as truths. Regardless, the uncertainty works the same way: by kneecapping us after piling the past on our shoulders, it leaves us flat on the lawn with Gene, unable to look away from the “blackened, shriveled body of a child.”

It seems painfully obvious, now, but stories about children being harmed, taken, or killed hit a lot harder after you have a kid. My errors and regrets, the things I did while younger and dumber and drunker, are infinitely minor compared to Gene’s, like pilfering candy from a gas station versus intentionally running over twelve people while fleeing the scene of a children’s hospital robbery. I’m not a deadbeat dad in a telltale heart tale. But it’s still that sort of fear, now that of a new, first-time parent, that draws me back to the story, if for no other reason than to stare into the abyss and find myself worthy.

Of course, my initial worry turned out to be unfounded. When they brought Zelda to me to be held skin-to-skin while they stitched up her mother, and later while I held her in the crook of my arm while the sun went down and I gave her a bottle, or even now, as she sleeps in the room next to my office after a morning spent watching her page through board books and solve brightly-colored, birch-wood puzzles, our bond has grown and grown and I have found in myself a loving father who was already there. It is hard at times, when her mother is away from home for her medical residency, and it has been hard to adjust to the shifting of priorities, but my love for her is the most intense kind I’ve ever felt. “The Bees” is one hundred percent, additive-free parental nightmare fuel, from the inexplicable screams to the accidental and intentional harms to the final body bags. And Gene and Karen and Frankie’s burnt-out house is a memento mori, a reminder to cultivate all the benevolent, jovial love that an imperfect, Midwestern father can give.