Because of the pandemic, the last time the Hemingway Society held their Biennial Conference was in 2018, in Paris. There, plenary sessions and paper presentations were held at the Sorbonne, and scholars from all over the world converged on the city Hemingway is perhaps most well known for. This year, the Society will meet for the first time in four years, in part, in the tiny town of Cooke City, Montana, located high in the Absaroka Mountains along the Montana-Wyoming border. On the one hand, Cooke City isn’t near anything—the nearest airport is three-plus hours away—but on the other, it’s right next to everything: the town sits in a valley encircled by glaciated horns and peaks; in summer, dozens of rivers and streams thread an alpine landscape so full of natural beauty and vitality as to be almost psychedelic. And it was here, for a roughly a decade from 1928 to 1938, that Hemingway found a home and a creative life that fostered some of his most famous works, including the first chapters of his anti-fascist masterpiece, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

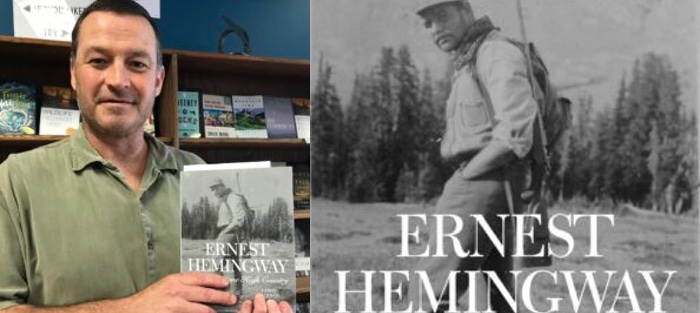

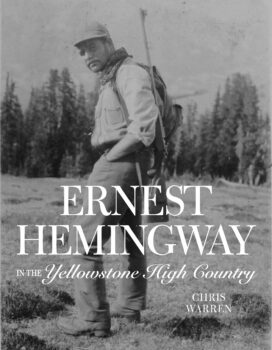

Yet almost none of this was known, or could be found, in the Hemingway criticism and scholarship of the last fifty years. That is, until writer Chris Warren, published his book on the subject, Ernest Hemingway in the Yellowstone High Country (Riverbend Publishing), in 2019. Warren has lived in these mountains for nearly thirty years, and his book strikes a balance between mapping Hemingway’s biography in the area (early on, Warren frames the geography as “Yellowstone High Country” because 1) topographically it is autonomous, 2) and because the rivers, mountains, and roads constantly criss-cross the conventional Montana-Wyoming borderline) with a reading of how the area found its way into Hemingway’s fiction.

Recently I caught up with Warren (who from July 21 to 23 will be directing the conference in Cooke City) to talk about the book and to talk a little bit about some of Hemignway’s short fiction. We begin the conversation with a discovery Warren made about Hemingway’s last published short story, “The Man of the World.”

Interview:

George McCormick: How did you come across “The Man of the World” in the first place?

Chris Warren: While working on my book, I was first focused on the 1928-1939 time frame in which the book takes place. But after reading works like Across the River and into the Trees and True at First Light and finding references to the Yellowstone High Country, I decided that I had to read absolutely everything. So I picked up the Finca Vigia Edition of the Short Stories and started working my way through them. “A Man of the World” was published in 100th Anniversary Edition of the Atlantic Monthly in 1957 and then essentially disappeared until this collection was published in 1987. As soon as I read it and realized that the action takes place in two fictional bars named The Pilot and The Index, which are two actual mountains just a few miles from my house, it became obvious that this story was set in Cooke City.

One of the arguments that your book makes is that there’s been a gap, or a blind spot over the years in Hemingway biography and criticism. What does this short story have to do with that?

One of the arguments that your book makes is that there’s been a gap, or a blind spot over the years in Hemingway biography and criticism. What does this short story have to do with that?

In Hemingway scholarship, it is important to know what happened and when and where things were written. After leaving the L—T Ranch for good in 1939, Hemingway would publish only four more short stories in his lifetime: two children’s stories called “The Good Lion” and “The Faithful Bull” in 1951, then “Get a Seeing Eye Dog” and “A Man of the World” in that issue of the Atlantic. When we turn to Carlos Baker’s mammoth biography, Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story, in chapter 74 we find that “A Man of the World” was the last published story written in his lifetime. I presented a paper to the Hemingway Society at the 2018 Conference in Paris making the case that this story was set in Cooke City, Montana, even though Hemingway renames it Jessup. That means that in the fifty-one years since its publication, no one from the world of Hemingway had been able nail down a setting for his final short story—this was a gap in the scholarship.

Tell me about the connection between The Yellowstone High Country and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.”

The primary connection is the 1912 murder of Jim Smith. As Harry lies dying under a tree in Africa, he drifts into dreamlike italicized flashbacks and laments all the things he hasn’t written. Towards the end of the story, he asks himself, “What about the ranch and the silvered gray of the sage brush…?” He then goes on to tell the story of a chore boy who is left to watch over the ranch and instructed not to give out any hay to other ranchers in the area. Jim Smith, who used to employ the boy, comes to the ranch to take some hay. When the boys says no, Smith blows him off, and next the boy shoots and kills him. Then Harry skis the boy and the body to town to face the music. While Hemingway in “Snows” calls them the “half-wit chore boy” and “the old man,” they were actually real people named Tony Rodescheck and Jim Smith. The latter being the original homesteader of what would become the L—T Ranch; Jim Smith Peak towers above the ranch to this day, and the murder was eventually ruled justifiable homicide, as was the custom of the day.

The other half of the story has to do with Harry irrationally berating his wife Helen while she tries to care for him. The abuse is vicious and unnecessary; much of it is because her wealth emasculates him and now, he is there helpless while she cares for him. Hemingway’s wife Pauline came from such wealth; her Uncle Gus bought them a car and the house in Key West and funded the Safari to Africa. I believe this part of the story has its roots in the author’s six-week stay in St. Vincent’s hospital in Billings, Montana, after a crashing the car while leaving the ranch in 1930. His writing, fishing, and shooting arm was badly broken. Pauline came out to look after him, and while she was there, he was depressed and consuming too much bootleg liquor and morphine. Other Hemingway friends that visited left feeling more sorry for Pauline than for Hemingway. While this episode is documented in the short story “The Gambler, the Nun and the Radio,” Pauline is left out. But I think he channeled his insecurity about her wealth and his resentful abuse of her during his convalescence into the dialogue of “Snows of Kilimanjaro.”

Since you’ve read Hemingway so closely over the last decade, and since this interview is for a site dedicated to short fiction, I wanted to ask: what do you think we sometimes miss, or don’t consider, in Hemingway’s short stories?

Since this for Fiction Writers Review and is focused on short fiction, I will assume that most people who read this are familiar with the iceberg theory. This is a concept that governed all of Hemingway’s fiction, especially the short stories. He first explained this principle to George Plimpton in an interview for the Paris Review in 1958:

“If it is any use to know it, I always write on the principle of the iceberg. There is seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows. Anything you know you can eliminate and it only strengthens your iceberg.”

So, however straightforward a story might seem, however simple and declarative the words may be, it is up to the reader to uncover the seven-eighths beneath the surface.

The other important thing to consider when reading Hemingway is the close connection between the fiction and the biography. There are two schools of thought on this. One is that we must read, judge, and critique the work on its own, that a story must be able to stand alone and should be read this way. I adhere to the other one; that all the work is in some way fictionalized biography. The Nick Adams stories of In Our Time represent Hemingway’s childhood and his experiences in World War I; A Farewell to Arms, his first love; For Whom the Bell Tolls, his experiences in in the Yellowstone High Country and his time spent covering the Spanish Civil War. In the 1933 short story collection Winner Take Nothing, there are two stories about suicide and in the collection’s final story Nick Adams reappears, contemplating his relationship with his father while driving with his son. If we read these as stand-alone stories, they are good, but when we understand that these stories were written soon after the suicide of Hemingway’s own father, they take on more meaning and the rest of the iceberg is revealed.

This is an impossible question, so you can pass on it if you want. But what’s the short story you wish Hemingway would have written?

This is an easy one, and there is no way I’m gonna skip it. I have a few stories of my own that I don’t tell simply because no one would believe them and I think this story may have fallen into the same category for Hemingway. It is the story of his first bear, and it has been verified by biographers, local sources, and in his letters. It goes like this:

In 1930, during his first trip L—T Ranch ten miles east of Cooke City, a bear had been killing cattle up Crandall Creek at an alarming rate. The outfitters at the ranch had been asked to bait the bear and shoot it, and Ernest had asked if he could tag along. He had only been at the ranch for a couple of weeks and hardly knew these men: Ivan Wallace, Chub Weaver, Smokey Royce, and Floyd Allington, all of whom would go on to become close friends. They kindly gave him a horse named Goofy who promptly bolted into thick woods with Hemingway riding it. He gashed his face and knee badly, and neither he nor the hands could stop the bleeding. Ivan and Ernest rode to the Crandall Ranger Station and borrowed a car in order to make the sixty-mile dirt-road drive to Cody, Wyoming, for treatment. The only doctor they could find was a converted veterinarian named Dr. Trueblood who stitched him up and prescribed a bottle of Oscar Pepper whiskey for the pain (it was during Prohibition). The two men worked on the whiskey on the drive back to Crandall and then rode five miles up the river to where a bear was feeding on the mule carcass the men had used to bait it with. Hemingway, all bandaged up, shot the bear, and the whiskey was used to get through skinning process. When they returned to the ranch, Hemingway offered to buy Goofy from ranch owner Lawrence Nordquist. Feeling a little guilty about the whole affair, Nordquist suggested he buy another horse that was better for riding. Hemingway growled through his newly stitched up face, “I don’t want to ride him—I wanna shoot him for bear bait.”

So, while riding Goofy, with Ivan, Smokey, Floyd and Chub, with a little help from Dr. Trueblood and Oscar Pepper, Ernest Hemingway shot his first bear. That is the story I wish he had written.