Take a moment to answer the question posed by the title of this book. If your answer is yes, then consider:

Take a moment to answer the question posed by the title of this book. If your answer is yes, then consider:

- For whom do workshops work?

- Where do workshops work?

- When do workshops work?

- How do workshops work?

You’ll likely find yourself in territory similar to fiction writing: ambiguities, contradictions, and more questions than answers. As fiction writers, we don’t pose yes or no questions, so it makes sense that an investigation into our primary pedagogy wouldn’t either.

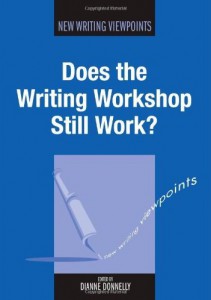

If you’ve followed scholarship debating creative writing—its position in the academy, ontology, professionalization, and pedagogy (to name a few issues)—you know that writers who perpetuate the traditional workshop have come under fire for not considering alternatives or for not reflecting on their pedagogies at all. If you haven’t kept up with the discourse, Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? (Multilingual Matters, 2010), edited by Dianne Donnelly, provides a foundation into creative writing studies in addition to new conceptions of what the workshop is and what it could be with revisions.

While the authors acknowledge the importance of new media, propose modified models of graduate training, and name specific practices—such as Leslie Kreiner Wilson’s “[a]nonymous floating workshop”—the collection is a theoretical and pedagogical study. We’re far beyond swapping unquestioned lore. Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? is by and large a scholarly inquiry into the workshop’s epistemology, elasticity, and value. These are complex issues and difficult questions; in this discussion rests the fate of creative writing in the academy, but there may be even more at stake than that.

Here is an abridged history of the past twenty years of creative writing studies. Scholars of composition, critical theory, and creative writing have debated: can it be taught?; should it be taught?; who has the authority to teach it?; what are we teaching?; and can it serve a diverse body of ever-changing students? (to name a few).

Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? offers an important and timely contribution to the discipline because—in addition to reiterating the censure of instructors who do not turn a critical eye onto their pedagogies, professionalization, and workshop methodologies—the collection complicates issues by asking readers to consider the workshop as an event, an artistic act, and a human activity. Despite all their relevant criticisms, these authors assert that the workshop doesn’t need to be dismantled, but conceptualized in completely new ways. Graeme Harper prefaces the collection by asking readers to see the workshop as “an exchange of human experiences” and creative writing as a thing “we do” rather than an object “we make.”

Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? offers an important and timely contribution to the discipline because—in addition to reiterating the censure of instructors who do not turn a critical eye onto their pedagogies, professionalization, and workshop methodologies—the collection complicates issues by asking readers to consider the workshop as an event, an artistic act, and a human activity. Despite all their relevant criticisms, these authors assert that the workshop doesn’t need to be dismantled, but conceptualized in completely new ways. Graeme Harper prefaces the collection by asking readers to see the workshop as “an exchange of human experiences” and creative writing as a thing “we do” rather than an object “we make.”

Harper, a seasoned contributor to the discipline, joins veterans Stephanie Vanderslice, Patrick Bizzaro, Anna Leahy, Tim Mayers, Brent Royster, David Starkey, Katharine Haake, Mary Ann Cain, and Joseph Moxley—all of whom have been publishing (in addition to their creative work) articles, full-length texts, or editing collections on pedagogy and disciplinarity for a number a years. Donnelly also includes newer voices in a collection that itself functions much like an effective workshop of passionate writers/teachers discussing the larger issues of craft and instruction relevant to the discipline.

Notably, Does the Writing Workshop Still Work?—and specifically Bizzaro’s chapter: “Workshop: an Ontological Study”—does an excellent job of showing creative writing as its own discipline with problems different from those of composition and literary studies, even if it has been influenced by these strands of English studies. This distinction is important because, rather than a subfield of composition, creative writing is its own strand. And perhaps, as Tim Mayers stated in his 2009 article “One Simple Word” in College English, creative writing studies “may harbor the roots of an institutional compromise in which the union between composition and literature does not involve one side winning and the other side losing, but rather both enterprises being transformed [by creative writing studies] so that they can meet on heretofore unimagined ground.” Any member of the academy knows how ugly these battles can get. English departments have imploded over less, but if creative writing might bridge this divide, it may one day even contribute to the survival of English studies in general. So, the work done in Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? may be important not only to our strand of English studies, but to all of English studies.

Notably, Does the Writing Workshop Still Work?—and specifically Bizzaro’s chapter: “Workshop: an Ontological Study”—does an excellent job of showing creative writing as its own discipline with problems different from those of composition and literary studies, even if it has been influenced by these strands of English studies. This distinction is important because, rather than a subfield of composition, creative writing is its own strand. And perhaps, as Tim Mayers stated in his 2009 article “One Simple Word” in College English, creative writing studies “may harbor the roots of an institutional compromise in which the union between composition and literature does not involve one side winning and the other side losing, but rather both enterprises being transformed [by creative writing studies] so that they can meet on heretofore unimagined ground.” Any member of the academy knows how ugly these battles can get. English departments have imploded over less, but if creative writing might bridge this divide, it may one day even contribute to the survival of English studies in general. So, the work done in Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? may be important not only to our strand of English studies, but to all of English studies.

Donnelly organizes the book into four sections: “Inside the Workshop Model,” “Engaging the Conflicts,” “The Non-Normative Workshop” and “New Models for Relocating the Workshop.” Beginning the first section, Vanderslice, in “Once More to the Workshop: A Myth Caught in Time,” advocates exercise-based, in-class writing, so students can see how a piece of writing comes together rather than as something finished and workshop-ready. Vanderslice points out that beginning writers need “content that enhances skill building and craft” so that they can understand the multiple ways of being a writer, reflecting, and producing work. In addition to his important ontological study, Bizzarro advocates that instructors “show students how to do the work of the workshop—to interpret and evaluate,” which are more examples of skill building students need prior to engaging in the workshop.

In the second section of the book, Royster considers the social dimensions of creative writing, a relatively new topic of inquiry in creative writing scholarship, but one that will be crucial to the discipline. He discusses the subjectivity of the author and argues that “[c]reative writing, in short, is both social and individual, and both identities are held within the self. As an alternative to the romantic ideal of the independent genius, the writer composes in response to specific environments and ideologies.” Royster advocates for instructors to help students locate themselves in a larger socio-cultural enterprise. Also in this section, Gaylene Perry looks at the vulnerable, but crucial, situation of “[carrying] out the practice of the art form” in hands-on writing workshops, which is also similar to Vanderslice’s emphasis on exercised-based, in-class writing.

In the second section of the book, Royster considers the social dimensions of creative writing, a relatively new topic of inquiry in creative writing scholarship, but one that will be crucial to the discipline. He discusses the subjectivity of the author and argues that “[c]reative writing, in short, is both social and individual, and both identities are held within the self. As an alternative to the romantic ideal of the independent genius, the writer composes in response to specific environments and ideologies.” Royster advocates for instructors to help students locate themselves in a larger socio-cultural enterprise. Also in this section, Gaylene Perry looks at the vulnerable, but crucial, situation of “[carrying] out the practice of the art form” in hands-on writing workshops, which is also similar to Vanderslice’s emphasis on exercised-based, in-class writing.

Although rhetorical awareness has traditionally been the concern of compositionists, Mayers engages the question of audience in creative writing. He proposes the workshop as a site for exploring the issue because it “provides apprentice writers with a responsive audience” and “[highlights] the variable and complicated ways in which writers think (or do not think) about the readers they one day hope to reach.” Composition theory is more prominent in chapter nine, “‘Its fine, I gess’: Problems with the Workshop Model in College Composition Classes.” Colin Irvine writes of the difficulties students have workshopping and discussing global writing issues (such as structure, context, and problematic patterns) in peers’ works in-progress. His contribution is significant because traditionally (in composition scholarship) instructors have been faulted; Irvine proposes that the problems are much more complex and have little to do with teachers. Although Irvine’s argument focuses on the composition classroom (but is rightfully included in the collection because it is about the workshop), it may indicate imminent reprieve for creative writing instructors, who have been accused of anti-intellectualism and even laziness in previous scholarship.

In the final section of the collection, “New Models for Relocating the Workshop,” Sue Roe proposes master classes that focus on practical technical skills as well as a real world understanding of the publishing industry. Similarly Haake, who has previously argued that curriculum should include professional institutional concerns, adds that students in workshops should be “encouraged to define for themselves precisely what might count as writerly, for whom and in what contexts” so that they might sustain their writing with inquiries that go beyond the classroom. These inquires are crucial because “exposing them to the hardest most complex writing problems of our age is the single surest way [ . . . ] for them to experience the primacy and imperative of writing, as writers do.” Finally, Cain complicates the question of the title. She proposes that it’s not about asking students if writing works or doesn’t but teaching them to look at how it works. Cain challenges the assumption that “the binaries that inform the question of ‘what works’” are fixed. “[T]he work of the workshop is, instead to ‘disorder,’ ‘deconstruct, and ‘tentatively reconstitute’ these totalizing assumptions.” Like Haake has done throughout her career, Cain is thinking bigger by engaging critical theory, and this foundational work will be as important to creative writing studies as the theorizing of composition studies was to grounding that discipline decades ago.

In the final section of the collection, “New Models for Relocating the Workshop,” Sue Roe proposes master classes that focus on practical technical skills as well as a real world understanding of the publishing industry. Similarly Haake, who has previously argued that curriculum should include professional institutional concerns, adds that students in workshops should be “encouraged to define for themselves precisely what might count as writerly, for whom and in what contexts” so that they might sustain their writing with inquiries that go beyond the classroom. These inquires are crucial because “exposing them to the hardest most complex writing problems of our age is the single surest way [ . . . ] for them to experience the primacy and imperative of writing, as writers do.” Finally, Cain complicates the question of the title. She proposes that it’s not about asking students if writing works or doesn’t but teaching them to look at how it works. Cain challenges the assumption that “the binaries that inform the question of ‘what works’” are fixed. “[T]he work of the workshop is, instead to ‘disorder,’ ‘deconstruct, and ‘tentatively reconstitute’ these totalizing assumptions.” Like Haake has done throughout her career, Cain is thinking bigger by engaging critical theory, and this foundational work will be as important to creative writing studies as the theorizing of composition studies was to grounding that discipline decades ago.

Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? concludes with Moxley’s commentary on the state of creative writing studies. Moxley—the editor of the earliest inquiry into theory and pedagogy, Creative Writing in America—reiterates his call for collaboration between all strands of English studies but states that questions and issues raised twenty years prior (regarding instructor’s anti-professionalism, and anti-intellectual attitudes) persist. He points to “the constraining force of the existing faculty reward system” that grants tenure to poets for their poetry and to fiction writers who publish fiction. Research and scholarship (and book reviews?) that are vital to the survival of our discipline don’t merit much; whereas, these are the critical components to the advancement of literature and composition studies. This is particularly chilling to someone who wants to write and teach in the academy—someone who understands the simultaneous impulse to write with academic ethos and connect to others (not just academics) through language.

Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? concludes with Moxley’s commentary on the state of creative writing studies. Moxley—the editor of the earliest inquiry into theory and pedagogy, Creative Writing in America—reiterates his call for collaboration between all strands of English studies but states that questions and issues raised twenty years prior (regarding instructor’s anti-professionalism, and anti-intellectual attitudes) persist. He points to “the constraining force of the existing faculty reward system” that grants tenure to poets for their poetry and to fiction writers who publish fiction. Research and scholarship (and book reviews?) that are vital to the survival of our discipline don’t merit much; whereas, these are the critical components to the advancement of literature and composition studies. This is particularly chilling to someone who wants to write and teach in the academy—someone who understands the simultaneous impulse to write with academic ethos and connect to others (not just academics) through language.

Nonetheless, I’m hopeful that discussions begun in Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? will spark further discourse among all threads of English studies, mark the beginning of similar projects to consider what Donnelly calls our “patchwork of practices,” and put workshop practitioners into conversation. Creative writing studies is, or can be, as Katharine Haake stated in What Our Speech Disrupts, a conversation with many voices and ideas rather than a revolution. Haake writes, “I am not convinced transformation is in order anymore, since it presumes consensus and, as in many things, our diversities continue to be among our greatest strengths.” Creative writing studies is very much like the workshop itself: multi-vocal, uncertain, and significant. The contributors of Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? assure us that there’s no need to dismantle the workshop, but reconsideration, further analysis, and more inquires—like the one they model in this collection—are in order.

Further Links and Resources

– This Table of Contents from Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? includes a full list of the book’s selections. You can preview or purchase the book at Book Depository or through Amazon.

– In case you missed Lee’s blog post about this last week, The Faster Times recently published a wonderful piece in which Deb Olin Unferth and George Saunders engage in a rational, practical, and, in the end, laudatory discussion of writing programs – a counterpoint to the voices raised against the model.

– Previously on FWR: Read Mary Stewart Atwell’s interview with Mark McGurl, author of The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing. (And we just can’t stop linking to Louis Menand’s essayistic review of said book.)