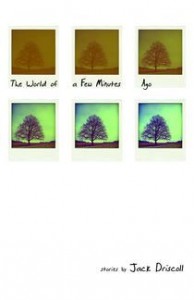

Few authors possess the range or emotional depth that one finds in Jack Driscoll’s new story collection, The World of a Few Minutes Ago, published this month by Wayne State University Press. Whether writing from the point of view of a twelve-year-old boy accompanying his father on a secret run to the slaughter house, or a seventy-year-old man reassessing both his fifty-year marriage and career as a war photographer, or a sixteen-year-old girl driving through a snowstorm with her driver’s ed instructor, Driscoll manages to seat the reader in the lives of his characters with grace, despite a roughness that often characterizes their lived experience.

Few authors possess the range or emotional depth that one finds in Jack Driscoll’s new story collection, The World of a Few Minutes Ago, published this month by Wayne State University Press. Whether writing from the point of view of a twelve-year-old boy accompanying his father on a secret run to the slaughter house, or a seventy-year-old man reassessing both his fifty-year marriage and career as a war photographer, or a sixteen-year-old girl driving through a snowstorm with her driver’s ed instructor, Driscoll manages to seat the reader in the lives of his characters with grace, despite a roughness that often characterizes their lived experience.

It is this human quality of the work that speaks to me so profoundly. That is to say, I can feel that these people genuinely matter to the author. That by writing about them, Driscoll is not only trying to give them voice, but to also better understand them. A writer just starting out may view his or her characters as puzzles to be solved, or, worse, as ciphers in the service of illustrating some abstract concept or theme. The writing, then, becomes an exercise to teach a lesson rather than an honest exploration of what it means to be human. As Tim O’Brien explains in his essay “The Magic Show”:

Above all, writing fiction involves a desire to enter the mystery of things: that human craving to know what cannot be known. … When writing or reading a work of fiction, we are seeking access to a kind of enigmatic “otherness”—other people and places, other worlds, other sciences, other souls. […] Beyond anything, I think, a writer is someone entranced by the power of language to create a magic show of the imagination, to make the dead sit up and talk, to shine a light into the darkness of great human mysteries.

In addition to Driscoll’s technical mastery of voice, and his compassion for his characters, the book also possesses an impressive emotional continuity. Longing and grief permeate this collection. Though not always immediately felt, these emotions lie below the surface of each story like permafrost, lending the book a feeling of structural integrity, to say nothing of depth.

It also makes The World of a Few Minutes Ago feel like a unified project. Driscoll asks larger questions that the collection as a whole wrestles to answer. What is the nature of longing? What does grief look like as we transition through different stages of our lives? For what we grapple with in our late thirties or early forties is quite distinct from what we feel in the ages preceding and following this “middle” period of our lives.

It is chronicling these middle years—the thirties and forties—where Driscoll’s art truly sings. The emotional terrain of one’s thirties, what Jane Smiley so accurately termed “the age of grief,” is captured here in all its beautiful messiness. That grief stems from having been on this earth long enough to know the score—to know that it often doesn’t get better, that the road ahead typically holds more of the same—and, in spite of all that, to still harbor the hope that one lucky break could change everything. After all, it’s a fine line between delusion and optimism, between knowing when to step out of the ring and when to give it one more shot.

stems from having been on this earth long enough to know the score—to know that it often doesn’t get better, that the road ahead typically holds more of the same—and, in spite of all that, to still harbor the hope that one lucky break could change everything. After all, it’s a fine line between delusion and optimism, between knowing when to step out of the ring and when to give it one more shot.

In “Saint Ours,” the narrator, Charlene, says:

My dad believed that the true worth of any life was how well you survived your own worst human share of it, and not how you warded it off, which he contended was impossible so why even try. Arguments I barely understood at ten years old, which is when he left us for good. But all things being equal, here I am, beaten up and down and sideways, but still intact enough at thirty-five to believe, against the odds, that the happier outcome the human heart was meant to act on is still possible, maybe. If that includes toughing it out for tips at the Day-Runner for a while, so be it. I mean—could be it’s as simple as this: We do what we do.

Similarly, there’s a fine line between abandoning a life and escaping it. Parents disappear in these stories, as do children. What’s so often at stake, then, is as much about who has been left behind as who has left. Because we can’t help but wonder how things might have been different. How our lives might have changed if we’d left or hadn’t, if our loved ones had finally gone, or perhaps had decided to stay. When Reilly Jack, the narrator of “Prowlers” (the story that opens this collection), wonders to himself, “And what are the chances that I’d end up here instead of in another life…,” he could be speaking for all the characters in these stories. The road not taken haunts this collection and gives it its heart.

In The World of a Few Minutes Ago, Driscoll deploys that nostalgia for what never happened as a kind of grace, if we could just let it be. If we could just live with our wounds and recognize in them the dignity that Charlene’s father counsels, if we could just free ourselves from their hurt. “Tell me, Clyde, something inconsolable about you that I could never guess,” a wife asks her husband in the collection’s title story, which closes the book. “Some murky reach inside you that you have never allowed me to see.” He does, though it’s not what she—or the reader—expects. So, too, reality subverts our expectations of what we thought our lives might turn out to be, what we envisioned for our futures.

In The World of a Few Minutes Ago, Driscoll deploys that nostalgia for what never happened as a kind of grace, if we could just let it be. If we could just live with our wounds and recognize in them the dignity that Charlene’s father counsels, if we could just free ourselves from their hurt. “Tell me, Clyde, something inconsolable about you that I could never guess,” a wife asks her husband in the collection’s title story, which closes the book. “Some murky reach inside you that you have never allowed me to see.” He does, though it’s not what she—or the reader—expects. So, too, reality subverts our expectations of what we thought our lives might turn out to be, what we envisioned for our futures.

We haunt and are haunted by our pasts, by the what-ifs of our lives. By melancholy and murk. And like the characters in these stories, who often find themselves staring through glass—whether standing outside their own lit homes, peering in from the blackest night, or staring out from a bright interior, trying to catch a glimpse of some phantom in the dark—the reality is the same: we are all prowlers of our lives. We all return to the sites of our abandonment, whether we were the ones leaving or the ones left behind.

Further Links & Resources

- Over at the Georgia Review you can read Jack Driscoll’s short fiction “That Story”—and his intimate description of why his work returns to the desolation of winter and to regular folk on the verge. He begins: “Perhaps nothing in this life is more fatiguing than boredom, but boredom is what we abided growing up, my small-town buddies and me.”

- On the Wayne State University Press page for Driscoll’s collection, you can download the sample story “This Season of Mercy,” find event information, and more.