In the summer of 2009, I met Elliott Holt at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. Our rooms were next door to each other and we were fast friends. In my experience, friendships made during the summer months at residencies and conferences can be ephemeral, more a product of the moment than a lasting connection. But thankfully that was not the case here: in the years after Sewanee, Elliott would become a close friend and one of my most trusted readers.

When we both discovered we were working on novels, we made a deal to exchange pages every Sunday via e-mail. We would not open the documents, unless instructed otherwise. We both needed something to help us stay on track. In those moments when I thought I couldn’t keep going, I was so lucky to be working alongside someone who would tell me, yes, you can. It was also inspiring to work alongside someone who was creating a book that was very, very special.

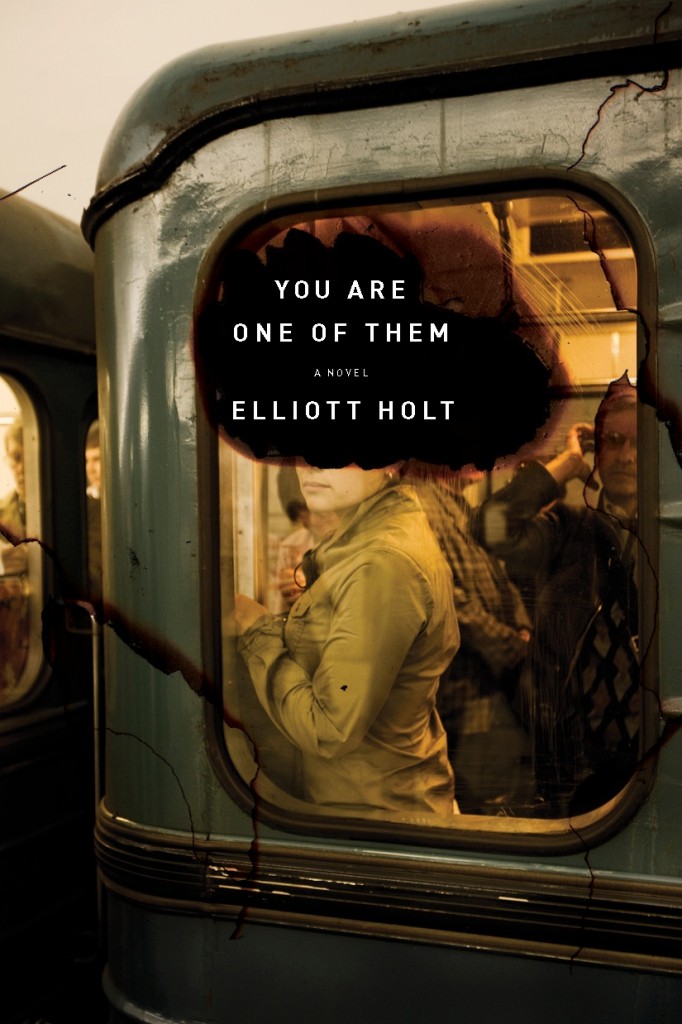

I want to tell you about the first time I read an excerpt of You Are One of Them. I was on a commuter train, traveling from Baltimore to D.C., where I was teaching at the time. Elliott had asked me to read the first couple chapters and so I printed them out and brought them along. Even though it was an early draft, I was knocked out by the voice, the mood, the mystery, the incredibly vivid evocation of America—and Moscow—at a particular time. After reading those chapters, I knew that Elliott would finish the book and that it would be remarkable.

With our days of page exchanging behind us, it was a joy and a privilege to chat with Elliott about her wonderful debut.

Interview

Laura van den Berg: Lorrie Moore once said, “A short story is a love affair, a novel is a marriage.” While it can certainly take me a good long while to write a short story, I found that novel writing required a new level of commitment. Was the same true for you? Can you describe how You Are One of Them came into existence?

Elliott Holt: You were instrumental in the process! Writing a novel does require a new level of commitment and it was daunting. I wasted a lot of time trying to figure out what I was doing and feeling overwhelmed by that large canvas. In the end, what helped the most was the deal that you and I made with each other: we sent each other new pages of our novels-in-progress every week. I’d tell myself, “Every five pages I write gets me five pages closer to a book.” I just had to keep writing, adding pages. Knowing that you were doing the same thing helped me so much.

You were instrumental for me, too! The routine of our weekly page exchange got me through some seriously rough patches. The battle against self-doubt was such a huge obstacle when working on my novel. Such a big canvas, so much time going down the wrong paths and then having to backtrack, so hard to know if it would amount to anything. Did you struggle with doubt too? Were there ever moments when you didn’t think you could make the book work? If so, how did you overcome?

Self-doubt is my biggest problem (on the page and off). I struggle with it all the time. It was late 2008 when I realized that I had a novel idea on my hands, but between then and the middle of 2011, there were many times when I was sure the book wouldn’t work. I abandoned it for most of 2010 because I didn’t think I could write it. (I had about eighty pages at that point, but I wasn’t happy with them.) In the end, I soldiered on because I didn’t have anything else that really mattered to me in my life. That sounds dramatic, but it’s true. A relationship ended and I was heartbroken, but I thought: I have no excuse to focus on anything but writing. At the end of 2010, I promised myself that I’d finish the book by the end of 2011. I worked like crazy on it that year. It was, in many ways, the loneliest year of my life. But my time was entirely my own that year (I’d saved up money from freelancing in advertising so that I could buy myself some uninterrupted writing time) and I was single-minded. It felt great to have such a clear purpose. And now I know that I can write a novel. And I’m excited to write another one. I just have to figure out how to overcome my self-doubt about my next writing project!

I remember that period, and I so admire the way you just fucking went for it. A lot of people wouldn’t have had the guts. I tell your story—the short version anyway—to students all the time, to demonstrate how, at a certain point, you have to stop hemming and hawing and dive in.

I also so clearly remember the very first time you told me about your novel. We were in a coffee shop in Park Slope, near your old apartment—what was the name of that place?—and you mapped out the story and it sounded incredible. Do you know what your next project is going to be? Or is it too soon?

I remember that conversation, too. We were at S’nice, right down the street from my place. You were so excited about my novel idea that I got excited about it again. I had practically given up on it at that point, but your enthusiasm motivated me.

I’m too superstitious to talk about my next novel idea (I’m still trying to figure out if it’s going to work), but I’m working on a couple of new short stories. It takes me forever to finish stories because I revise so much.

In your actual life, you lived in Moscow for a time. What was that like? Are the Moscow chapters in You Are One of Them the first time you’ve written about Russia?

I wrote a couple of lackluster stories in graduate school that were about Russia. One was set in Moscow, another one was about a Russian woman who comes from Moscow to New York. A teacher in grad school urged us to “own your material,” and at the time my material was expatriate life in general, and life in Moscow in particular. I’d spent five years in my twenties living abroad. When I started the MFA program at Brooklyn College, I’d only been back in the States for two years. I left Moscow in 2001 (after living there for two years) but it took me another seven years or so to really process the experience of living there.

I wrote a couple of lackluster stories in graduate school that were about Russia. One was set in Moscow, another one was about a Russian woman who comes from Moscow to New York. A teacher in grad school urged us to “own your material,” and at the time my material was expatriate life in general, and life in Moscow in particular. I’d spent five years in my twenties living abroad. When I started the MFA program at Brooklyn College, I’d only been back in the States for two years. I left Moscow in 2001 (after living there for two years) but it took me another seven years or so to really process the experience of living there.

What was the strangest thing about living there?

Man, where do I begin? When I first got there, what felt most surreal was the fact that I was there at all. During my childhood, Russia was a mysterious, inaccessible place, behind the Iron Curtain. And I had to get used to having much less personal space: privacy is hard to find there.

Sometimes I hear people talk about books as being either plot-oriented OR language-oriented, though of course many novels cast labyrinth plots in beautiful language—Michael Ondaatje comes to mind—and that attentiveness to both the larger canvas and to the line is something I love about You Are One of Them. Are you a writer who labors over individual sentences in early drafts? Or not until the later stages?

I don’t labor over individual sentences much in early drafts, but I do labor over voice and tone. Until the sound of a story clicks for me, I feel like I’m stalled, and everything I write ends up in the trash. With this book, I rewrote the first seventy-five or eighty pages countless times over three years. It was only when I found the right first sentence—three years after I started working on the book—that I really hit my stride. When the first sentence of Chapter 1 (“The first defector was my sister”) came to me, it unlocked the central metaphor of the book. And it unlocked the voice and the tone. Once I had that sentence, I wrote the rest of the book in a year.

And then in later drafts, I’m not laboring over individual sentences so much as thinking about the big picture: What is this story really about? What themes are emerging, and how I can pull them out and emphasize them? What scenes need to be there to make the plot work? This book is meticulously plotted, but the plotting didn’t happen at the beginning of the writing process. It happened after I had intuitive drafts to build from.

I know what you mean in terms of voice—it becomes an essential guide to both the individual sentence and the overarching story, a kind of north star. What are some of your all time favorite voices from works of fiction?

My favorite fiction is driven by voice. Some of my favorite examples are Nabokov’s Lolita, Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Mary Gaitskill’s Veronica, James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. And a masterful recent example: Claire Messud’s The Woman Upstairs, which was just published in April.

Claire Messud! I know you’re a big fan of her work, and her reply to this question in a recent Publisher’s Weekly interview generated a fair amount of conversation. When a student brings up “likeability” in class, I’m fond of reminding them that Rick Moody once called “likeability” the “hobgoblin of small minds.” To me, it seems among the least interesting or important attributes for a character to possess, so I loved what Messud had to say. As someone who’s written a protagonist who, while not as dark or desperate as Nora, still might not be considered conventionally “likeable,” how did Messud’s response strike you?

I always seem to agree with Claire Messud. In that interview she said:

If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t “is this a potential friend for me?” but “is this character alive?”

I can’t put it any better than she did. Humans are complicated creatures, full of apparent contradictions, and the most compelling characters in fiction are complicated, too. Humbert Humbert is a pedophile, but he’s a charming, entertaining one. Everyone has a dark side. I’d much rather read fiction with strong, complicated characters than with bland, eager-to-please ones.

Once Sarah reaches the dacha, there is this amazing uptick in energy that makes the last 100 or so pages wonderfully gripping. How long did it take for you to figure out what would happen once she reached the dacha?

I knew how I wanted the book to end, but I had to get there. I had to earn that ending. Part of the reason that dacha scene is so tense is because the process of writing it was tense. It was like walking a tightrope. I was working very intuitively—just imagining the scene and allowing myself to be surprised along the way—but I was also conscious of taking these small steps, creating these precise beats in the scene, working with subtext in the dialogue. It was like playwriting (which I used to do in college). I’m a terrible playwright, but reading Aristotle’s Poetics (plus a lot of Beckett and Pinter and Mamet plays) certainly helped my fiction writing.

And my brilliant editor, Andrea Walker (at the Penguin Press), was hugely helpful when I was revising the book. She saw what I was trying to do with the ending and understood exactly what kind of novel it wanted to be. Her notes were key to making those final scenes work.

I love the way your novel ends, the ambiguity—an outcome is suggested, but a degree of mystery remains. It seems to me that an ending like that is about redirecting the reader’s attention away from the literal mystery and toward the more complex, slippery mysteries of the self. Can you talk about the way you used a “surface” question/mystery (“is Jenny alive?”) to explore these other kinds of questions?

Several people have told me that they love the ending of this book, but that while reading it, they got scared that I, the author, had backed myself into a corner that I wouldn’t be able to get out of. “How is she going to make this work?” one friend told me he was thinking. I’m proud of the ending. It wasn’t easy to make it work, but I think I pulled it off.

Several people have told me that they love the ending of this book, but that while reading it, they got scared that I, the author, had backed myself into a corner that I wouldn’t be able to get out of. “How is she going to make this work?” one friend told me he was thinking. I’m proud of the ending. It wasn’t easy to make it work, but I think I pulled it off.

As for the tension between the surface mystery and the complex mysteries of the self: this is a book about the way our lives are shaped by history (cultural and personal), and it’s also a book about the obsessive nature of grief. I think grief turns us into detectives, trying to make sense of the loss, trying to understand the person who is no longer in our lives. Sarah’s fixation on her friend—and her friend’s fate—is tied to her own sense of self. So there is a mystery of sorts in this book, but it’s Sarah’s emotional arc that interests me. Sarah has spent most of her life as a footnote in someone else’s story. In this book, she finally tells her own. The surface mystery, as you put it, occupies her because she’s avoiding the larger questions about herself.

In a similar vein: I was reading an old interview with Zadie Smith and Ian McEwan in The Believer the other day and was struck by this passage (from McEwan):

And with the novel we have happened to devise this form, this very elastic, mutable form that can allow us moments of real human investigation. Milan Kundera says very wise things in this context. He lays a lot of stress on the novel as a mode of investigation. It’s an open-ended way of looking at our own image, in ways that science can’t do, religion’s not credible, metaphysics is too intellectually repellent on its surface—this is our best machine, as it were.

Does this vision of the novel resonate with you?

Yes. Completely. I do think of the novel as a form that allows us moments of “real human investigation.”

I know McEwan doesn’t necessarily mean “investigation” literally, but that quote got me thinking about how some of my most beloved novels revolve around a mystery the narrator is trying to solve. Javier Marías’ Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me, which begins with an enigmatic death, and Yoko Tawada’s The Naked Eye, which begins with an abduction, spring to mind as two of my most essential “grief detective” novels. What are some of yours?

The Virgin Suicides is a perfect example. And The Great Gatsby is basically an elegy (that wistful tone!). Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day and Barnes’s A Sense of an Ending come to mind. I love novels in which the narrator is looking back, trying to make sense of events. Those books are less about the events themselves than about the narrator’s (often fractured) memory of them.

Going back to Zadie Smith: in her “Rules for Writers” in The Guardian, she advises writers to “Resign yourself to the lifelong sadness that comes from never being satisfied.” I remember reading this and thinking, “Oh, that seems exactly right.” Your thoughts?

That is exactly right. Zadie Smith is a genius, as usual. I am never totally satisfied with my work. The story or novel we imagine never ends up as good as we hope it will be. But that tension between what we want to do and what we actually achieve is what keeps us going. It’s motivating. I’m aware of all my book’s flaws. I keep telling myself the next one will be better. But I’m sure I won’t be satisfied then. It’s okay. I’m resigned to it.

In his lectures on literature, Nabokov (God, I love him) talks about the Russian word, toska, which has no equivalent in English. As he puts it:

No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases it may be the desire for somebody of something specific, nostalgia, love-sickness. At the lowest level it grades into ennui, boredom.

I am quite familiar with toska.