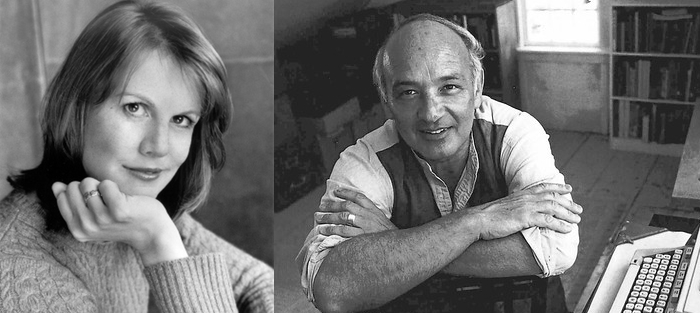

Editor’s Note: In honor of Nicholas Delbanco’s retirement from the University of Michigan, Fiction Writers Review is dedicating this week’s content to a celebration of Delbanco’s influential career as both a writer and a teacher. Delbanco is the author of nearly 30 books of fiction and non-fiction and is the recipient of numerous awards. On December 4th, a symposium entitled “The Janus-Faced Habit: The Art of Teaching and the Teaching of Art” will take place in Ann Arbor as part of a tribute to his legacy.

Nicholas Delbanco, author of a prodigious list of novels, essays long and short, short stories, reviews, and textbooks—have I missed anything?—was one of my several remarkable advisors and mentors at the University of Michigan a decade ago now. I didn’t meet him there, however. In one of those odd circular windings of life’s staircase, I met Nick when I was a seventeen-year-old freshman at Warren Wilson College, a desperately wannabe young writer with little to say. He was the first professional writer I’d ever actually met, an important occurrence in the life of every beginner; in fact, Nick himself would later regale his graduate seminars with the parallel encounter in his own childhood—pleasant family acquaintances who turned out to be H. A. and Margot Rey, the creators of Curious George.

On that occasion when he visited Warren Wilson for a week of readings and seminars, his coming was presaged by posters and library displays. I was fascinated by the idea that a live human being called himself a writer; up to that time, I’d been under the impression that they had all died by about 1940 (most of them, in fact, by 1895). He arrived, with his beautiful young family in tow, to critique our fledgling efforts, and his praise of my short story stayed with me for years as encouragement. I was thrilled that this elderly and distinguished writer (he was 40) seemed to think I had some kind of adroitness on the page.

I saw his teaching gifts again, many years—and for him, many books—later, when I arrived as a graduate student at the University of Michigan in 2002. Nick, while generous about our work, was tough in his teaching; we were writers-in-training. He required us to try hard, in our discussions, and in the stories we turned in. Most of all, he modeled a steadiness about writing. “I got up early this morning,” he’d say in our evening fiction workshop, which rolled around for him after a twelve-hour day of teaching and meetings, “and I wrote for an hour, first thing. An hour isn’t much, perhaps, but you can do a great deal in an hour.” If one of us exclaimed over Nick’s productivity, all those books in the midst of a busy teaching career, he would say, “It’s mostly habit. Years ago, I formed the habit of getting up early and writing.” We learned from him about the importance of persistence, as much as about prose style or character development.

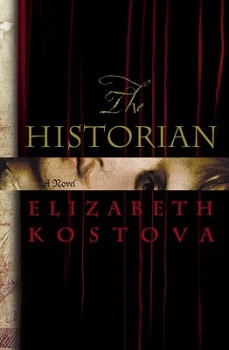

In my application to the MFA program at Michigan, I’d mentioned that I was working on a novel, although I hadn’t sent any pages of it and I also didn’t submit any to that first workshop. In fact, I had vowed to myself that I’d keep it under wraps, because it had a supernatural element and everyone else was talking about Steinbeck and Alice Munro (both of whom I liked, too). One day Nick said to me, kindly but pointedly, “What about that baggy monster with which you wrestle—your novel? Why don’t you bring in a little of that and let us have at it?” It took me weeks to suddenly recognize the reference to my own favorite novelist, Henry James, who called a certain breed of nineteenth-century novels “large loose baggy monsters.”

In my application to the MFA program at Michigan, I’d mentioned that I was working on a novel, although I hadn’t sent any pages of it and I also didn’t submit any to that first workshop. In fact, I had vowed to myself that I’d keep it under wraps, because it had a supernatural element and everyone else was talking about Steinbeck and Alice Munro (both of whom I liked, too). One day Nick said to me, kindly but pointedly, “What about that baggy monster with which you wrestle—your novel? Why don’t you bring in a little of that and let us have at it?” It took me weeks to suddenly recognize the reference to my own favorite novelist, Henry James, who called a certain breed of nineteenth-century novels “large loose baggy monsters.”

Encouraged, if reluctant, I brought in some pages, and found that my obsession with crypts and Béla Lugosi was as welcome in Nick’s classroom as any sparely framed short story. The serious critique of that workshop was an enormous help to me as I completed my first novel, The Historian, which I’d intended to keep nailed in its coffin throughout graduate school.

Most of all, I enjoyed the sense Nick conveyed, in that class and others I later took with my cohort, that writing is about much more than the parts of its forms or the flow of a voice. For him, it was and is not only about language, story, structure, character development, emotion; it’s also—and here his own book list bears me out—about history, culture, etymology, tradition. He writes with equal elegance about camping in Namibia and listening to a string quartet, about the politics of eighteenth-century Europe and the poems of Thomas Hardy. His love of music, art, travel, and expertise of all kinds gives his work a layered depth that really does belong to that nineteenth century in which my young self thought all writers had died out. His love of word-play and of the dazzling varieties of prose style in English filled a course he created at Michigan using the imitation of great stylists to learn the possibilities of our own craft (Joyce, Faulkner, Woolf, Hemingway).

In fact, no conversation about writing, for Nick, is without its corollary discussion of reading—this in a day when too many young writers don’t venture farther back in their self-education than his own birth date. His approach to writing is also practical. Some years after graduation, when I complained to him that I was feeling stuck on my new novel, he suggested I write just forty pages of it, any forty pages, polish them to a high luster, and let them remind me that I had the skill to write the rest. That worked, of course, to hold the baggy monster long enough for me to put a leash on it.

It’s a little hard for those of us who’ve studied with Nick over the years to imagine Michigan’s MFA without his daily presence there, but of course it won’t happen like that. The brilliantly endowed program he built from modest beginnings, the Hopwood Awards expertly administered and encouraging to hundreds of young writers, the tone of generous camaraderie and literary adventure and seriousness of purpose, are all so thoroughly woven into its fabric that you couldn’t take those out without packing away the whole tapestry. It’s nice to think, at the same time, that he’ll have unstinted hours with his morning habit (and that those hours will stretch into whole days); with his adored family and friends; with the art and music he loves, the last one or two books in the Western canon he hasn’t read. For younger writers, he provides a permanent record of both diligence and wit. “This moment always touches me,” he would say at the beginning of a new class. Exactly.