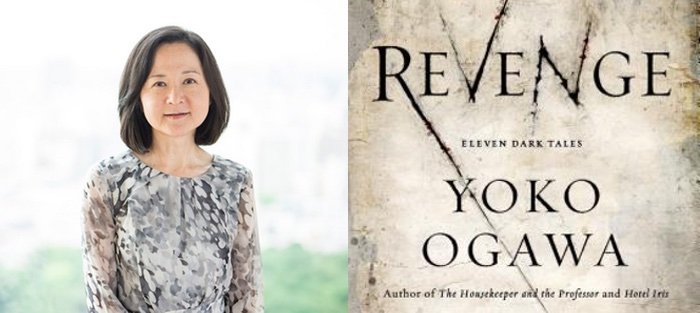

Editor’s Note: This is Part II of Elizabeth Mayer’s essay on strange objects in fiction. Read Part I first for an introduction to the topic and an in-depth reading of Joy Williams’s “Congress.”

1. A bag is patience; a bag is profound discretion.

Yoko Ogawa’s “Sewing for the Heart” is told from the first-person perspective of the main character—an unnamed bag maker who lives in a small apartment over his shop with only his pet hamster for company. His life is simple. He explains: “I have only myself to please, and that doesn’t take much.” Though his interactions with other people are limited, the intimacy he shares with the bags he creates is deep:

Compared with the world upstairs, my life with my bags below is quite rich. I never weary of them, of caressing and gazing at my wonderful creations. When I make a bag, I begin by picturing how it will look when it’s finished. Then I sketch each imagined detail, from the shiny clasp to the finest stitches in the seams. Next, I transfer the design to pattern paper and cut out the pieces from the raw material, and then finally I sew them together. As the bag begins to take shape on my table, my heart beats uncontrollably and I feel as though my hands wield all the powers of the universe.

The closeness of the bag maker’s relationship to his bags is evident through careful diction. He refers to his “life with [his] bags” as “quite rich,” as if the bags were his family members. The language he uses to express his admiration of them is oddly sensual: he never tires of “caressing and gazing at [his] wonderful creations.” This line seems both erotic and predatory. The relationship is not mutual. The bag maker is in control. The bags are his “creations,” his to caress and gaze at as he wishes.

We see the narrator’s obsessive nature in the meticulous step-by-step description of his creative process. The bag begins in his mind, and then he sketches “each imagined detail” down to “the finest stitches in the seams.” The minute intricacy of his sketches is revealed in these tiny seam stitches, stitches barely visible in a tangible bag yet still attended to in his design. The language of the actual construction of the bag is reminiscent of surgery. The image of the narrator “cut[ting] out the pieces from the raw material,” especially with the usage of the word “raw,” brings to mind meat being cut. The material of the bag becomes a kind of flesh, which then “take[s] shape on [his] table.” Here, the word “table” is at once surgical. When the bag maker explains how his “heart beats uncontrollably and [he] feel[s] as though [his] hands wield the power of the universe,” it is as though he has become the mad scientist and the bag his monstrous creation. The physical reaction of his heart beating “uncontrollably” points again to the erotic nature of his relationship to his bags. His creations produce in him feelings of power as well as sexual excitement.

The narrator expounds on his admiration of the bags:

Now, you may be wondering why I get so excited. You may be thinking that a bag is just a thing in which to put other things. And you’re right, of course. But that’s what makes them so extraordinary. A bag has no intentions or desires of its own, it embraces every object that we ask it to hold. You trust the bag, and it, in return, trusts you. To me, a bag is patience; a bag is profound discretion.

After the heightened description of his response to the bags, the narrator switches suddenly to second person, addressing the reader directly. This direct address makes it feel as though the narrator is justifying his actions. While this address does provide further explanation, it also serves to draw greater attention to the bag maker’s fervor. The repetition of the “you may be” clause acts as a direction to the reader. If we had not previously questioned the narrator’s strange affinity for his bags, we now, at his suggestion, clearly do. His reasoning, however, for his devotion to his bags is quite eloquent. Though the bag maker knows we “may be thinking that a bag is just a thing in which to put other things,” he argues that this is “what makes them so extraordinary.” Here, our idea of normalcy is subverted. It is precisely the simplistic nature of the bags and their singular function that makes them, to the narrator, “so extraordinary.”

As the narrator’s explanation continues, the descriptions of the bags take on more humanistic connotations. The narrator tells us that “a bag has no intentions or desires of its own.” To even consider the possibility of a bag having “intentions or desires” has elevated the bag to something more than mere object. The narrator admires how a bag will “embrace every object that we ask it to hold.” Here, the bag is an active participant. It embraces its contents, which are, pointedly, objects. These are things that “we ask it to hold.” In the narrator’s mind, we do not simply drop our belongings into a bag; rather, the use of the bag constitutes a conversation.

As the narrator’s explanation continues, the descriptions of the bags take on more humanistic connotations. The narrator tells us that “a bag has no intentions or desires of its own.” To even consider the possibility of a bag having “intentions or desires” has elevated the bag to something more than mere object. The narrator admires how a bag will “embrace every object that we ask it to hold.” Here, the bag is an active participant. It embraces its contents, which are, pointedly, objects. These are things that “we ask it to hold.” In the narrator’s mind, we do not simply drop our belongings into a bag; rather, the use of the bag constitutes a conversation.

Once again, the language hints at sexuality: “intentions,” “desires,” “embrace,” “hold.” This is the language of sexual negotiation, and it is notable that the narrator enjoys that the bag has none of its own “intentions and desires.” The humanizing of the bags continues when the narrator insists that “you trust the bag, and it, in return, trusts you.” The notion of placing trust in an inanimate object is both strange and true. Whether consciously or not, we do trust a bag to carry whatever load we place in it. The idea, however, that the bag returns that trust reveals the instability of the narrator’s mental state. The narrator further asserts that “a bag is patience; a bag is profound discretion.” Something seems to be amiss in this summation. For a bag to be “patience,” we may assume that it is enduring some annoyance or aggression. Is the narrator suggesting that a bag is submissive? When the bag maker says that “a bag is profound discretion,” there is the implication of hiding. What, we may wonder, in the bag maker’s life, requires this “profound discretion?”

The action of the story begins when a young woman visits the bag maker with an unusual request. The narrator relays the experience and his stunned reaction:

I can make any kind of bag a customer wants: bags for artificial limbs, bedpans, rifles, eggs, dentures—any size and shape you can imagine. But I have to admit I hesitated when she told me her request, one I had never heard before and I’m sure I’ll never hear again.

“I would like you to make a bag to hold a heart.”

“A heart?” I blurted out, thinking I must have misunderstood.

From the beginning of this passage, the reader is off-kilter. The narrator claims he can “make any kind of bag” and begins reciting matter-of-factly the kinds of bags he has made in the past. The casualness with which he delivers this list of bags belies the oddness of the items listed. The bags themselves are described by what they are designed to hold: “artificial limbs, bedpans, rifles, eggs, dentures.” Though perhaps easily overlooked upon first reading, under closer examination this list is far from normal. The contents point toward bodily harm, illness, and decay. The grisly nature of the list sets a subtle tone of unease.

Despite the narrator’s experience in the crafting of strange bags, he emphasizes his surprise at the current request, building suspense by telling us that it was one he “had never heard before” and would “never hear again.” In combination with the preceding list, the narrator’s assertions serve to unsettle the reader and build tension, increasing the impact of the actual bid for “a bag to hold a heart.” The woman’s request stands alone as a single line of dialogue without modifiers. Letting the line stand alone creates a sort of resonant quality, like that of a bell being struck by a hammer. It focuses our attention and underscores the line’s importance. The “blurted out” response of the narrator—“‘A heart?’”—then follows like an exclamation point. Here, in this passage introducing the bag for the heart, the reader’s attention is immediately arrested through tension and surprise. Our reaction to the story mimics the narrator’s shock at the woman’s request. Curiosity drives the story forward.

2. Its location made it extremely vulnerable.

The narrator agrees to attempt to accommodate the woman’s request. She explains that she has been turned away by several other shops, but she has heard of the narrator’s prowess for making any kind of bag. Before we are given the precise reason for the bag, the woman details her previous trials:

“I’ve tried everything,” she said. “Silk, cotton, nylon, vinyl, paper . . . nothing is right. It has to be kept warm—heat loss can be fatal—but then there are the secretions. If the material is too absorbent, it sucks up all the moisture. But then again, something like vinyl doesn’t breathe.”

She had explained that she was born with her heart outside her chest—as difficult as that might be to imagine. It worked normally enough, but its unique location made it extremely vulnerable.

Before we learn the explicit details of the woman’s condition, we are told of her struggles in constructing an effective bag. Her desperation is evident in the absoluteness of her assertions that she has “tried everything” and found “nothing is right.” Here, the woman’s list of fabrics contrasts sharply with the narrator’s earlier list of objects. Compared to the bag maker’s grim set of items, the woman’s catalogue of “silk, cotton, nylon, vinyl, paper” connotes a sense of smoothness. Her list is stark and clean.

The language, however, soon turns visceral. It has to be “kept warm” for “heat loss can be fatal.” Here, the heart is depicted almost as if it is a separate creature, a distinct entity that exists separate from the woman, a newborn animal that must be carefully protected. The difficulty of caring for the heart is apparent in the need to maintain the proper balance of moisture. The word “secretions” adds an element of repulsion to the scene, contrasting the cleanliness of the opening list. It isn’t until after the woman has explained these complications that the narrator states the situation clearly: “She was born with her heart outside her chest.” The passage of dialogue serves to heighten the suspense. After, when we are told the exact physiognomy of the heart, we understand the precariousness of the situation. The narrator enforces this idea when he states that the heart is “extremely vulnerable.”

Though the task is strange and complicated, the narrator is determined to “satisfy” the woman. Once again, the word “satisfy” here hints at the sexual. He explains to her that he thinks “seal skin would be ideal,” remarking that “‘It’s soft and strong, and it repels moisture while providing superior insulation—just what a seal needs.’” The seal skin marks a sharp diversion from the fabrics the woman has listed. Her attempts before have involved natural and manmade fibers, but the bag maker’s first suggestion requires the skin of another creature. The material he chooses involves butchery. This idea is enforced when he comments on the attributes of the skin, describing them as “just what a seal needs,” acknowledging that the leather was once the flesh of a living animal. Though she agrees that the seal skin “sounds perfect,” the woman continues to list the complexities of the task. “I’m afraid the shape will be a bit complicated,” she says, “It has to be sturdy but not damage the membrane,” and she goes on to insist, “It needs to have a snug fit. Too loose and it rubs the sack around the heart, but if it’s too thick it cuts off the circulation. It’s a matter of striking the right balance.” As she repeats the delicate requirements, we see that the bag maker has not yet won her trust. She has been through all this before with other craftspeople, and none, so far, have succeeded. Here, also, we see for the first time the physical similarity between the heart and a bag. The membrane around the heart is referred to as a “sack.” Only a short while later, she says of the bag, “it’s not just a simple sack.” By using the word “sack” to refer to both her heart and the bag, a clear connection is drawn between the two.

The parallel between the woman’s heart and the bag itself continues as we witness the naked heart and the bag maker’s reaction to it. The woman undresses and reveals the heart. The bag maker expresses his astonishment: “I was shocked to see the heart beating—for some reason, I had imagined it would be inanimate. But there it was, pulsing and contracting. It seemed to cringe under my gaze.” Like the bags he crafts, the narrator pictures the heart as “inanimate.” The movement and liveliness of the heart “shock” him. When he directs his “gaze” onto the heart, unlike his bags, the heart “seem[s] to cringe.” With the heart’s reaction, we can see there is something aberrant in the narrator’s gaze. While the bags submit patiently, the heart reacts in defense. Here, also, we see that the narrator has disassociated the heart from the woman herself. The heart “cringe[s]” of its own volition. The rest of the woman’s body does not interest him. He feels no desire for her breasts. Instead, he tells us, “I found myself longing to caress her heart.” Once again, the narrator uses the same language in regard to the heart that he used earlier to describe his relationship to his bags. He wants to “caress” the heart, just as he caresses his own creations.

The bag maker is intensely attracted to the heart. His desire increases rapidly as the story continues. He further describes the heart and his impulses toward it:

It could fit in the palm of my hand. A pale pink membrane of delicate muscle tissue surrounded it. What extraordinary, breathtaking beauty! Would it feel damp if I cupped it in my hands? Would the membrane rupture if I gave it a squeeze? Could I feel it beating? Feel it shrink from my caresses? I wanted to run my fingertips over each tiny bump and furrow, touch my lips to the veins, soft tissue to soft tissue, the pressure of her pulse against my skin . . . I could easily lose myself to these thoughts, but I knew I had to keep my desire in check, had to play my role and make the perfect bag for this heart.

The description is fraught with the bag maker’s desire to hold the heart. The heart’s size is explained in relation to the “palm of [his] hand.” Once again, the “pale pink membrane of delicate muscle tissue” is reminiscent of one of the narrator’s bags. His attraction can be seen in his exclamation appreciating the heart’s “breathtaking beauty!” He is stunned by the heart’s physicality. He finds it, quite appropriately, “extraordinary.”

While the bag maker deeply admires the heart’s beauty, there is something increasingly predatory in his desire to touch it. He imagines how it would feel if he “cupped it in his hands.” Here, the verb “cupped” connotes the cradling of a breast. Soon, however, his thoughts turn violent. He goes on to wonder if the “membrane [would] rupture if [he] gave it a squeeze.” He wants to “feel it shrink from [his] caresses.” It is apparent that part of his attraction stems from the cringing and shrinking of the heart. The fear of the heart, as the bag maker perceives it, is alluring. From these brutal musings, the language quickly turns sensual. He wants to “run [his] fingertips over each tiny bump and furrow, touch [his] lips to the veins, soft tissue to soft tissue.” These are sexually charged images expressing intense desire. Interestingly, the woman whose body to which the heart is attached is mentioned only briefly, in reference to “her pulse.” It is not the woman the narrator wants, but her heart. The strength of his feelings are underscored when he explains how he must concentrate to “keep [his] desire in check” so that he can “make the perfect bag for this heart.” Here, it is notable that the “her” is missing. The possessive pronoun is absent because it is not the woman with whom he is concerned. Rather, the bag he longs to make will be for the heart.

The narrator’s desire for the heart haunts him. He goes to see the woman, who is a singer, perform in a dingy nightclub because he “simply wanted to see her heart in the outside world.” His secretive, stalker-like actions enforce his growing obsession with the heart. As he watches her sing, he indulges in violent fantasy:

I wondered what would happen if I held her tight in my arms, in a lover’s embrace, melting into one another, bone on bone . . . her heart would be crushed. The membrane would split, the veins tear free, the heart itself explode into bits of flesh, and then my desire would contain hers—it was all so painful and yet so utterly beautiful to imagine.

His daydream moves quickly from “lover’s embrace” to the “crushed” heart. The language is both violent and reminiscent of sexual climax. The membrane “split[s],” the “veins tear,” and the heart “explode[s] into bits of flesh.” In his fantasy, the consummation of the bag maker’s desire results in destruction. In this way, his “desire would contain hers.” Here, the bag maker and his desire match the shape of a bag. He wants to become a container himself, enveloping the destroyed heart.

3. It was indeed a strange bag.

His desire drives the creation of the bag. Eventually, the bag takes on its corporeal form. The narrator describes it in careful detail:

It was indeed a strange bag. The complicated shape of it was difficult to achieve. I had assembled nine different pieces of leather into an asymmetrical balloon with seven holes of varying size. The bottom of it was an oval, but the bag tapered toward an opening at the top that fastened with hooks. The strap for her neck was long and somewhat awkward, as the leather hadn’t had time to soften. I was afraid she might get tangled in it.

It looked like a spider, or a work of modern art. Or a fetus that had just started to grow.

The bag is like a puzzle. The bag maker himself remarks on its strangeness and the “complicated shape.” Though we are given specific numbers—“nine different pieces of leather” and “seven holes”—the image of the bag is difficult to conceive. The descriptor of an “asymmetrical balloon” seems to confuse the idea that the bag is made of so many separate parts and contains several holes. If it were a balloon, it would be quite deformed and nonfunctional. The hooks and long neck strap fashioned from leather that “hadn’t had time to soften” are reminiscent of some sort of sadomasochistic bondage instrument. The narrator’s fear that “she might get tangled in it” simply reinforces the suggestion that it could be used as some sort of restraint. The narrator’s disparate similes—the bag as “a spider,” “modern art,” or “a fetus”—also give us conflicting ideas of the bag’s physicality. It is compared to both the animate and inanimate. The notion of the bag as a spider creates an innate sense of creepiness, while the comparison to modern art suggests a strange beauty. Perhaps the most unsettling of the comparisons is the bag as “a fetus that had just started to grow.” Here, the bag is taking on a life of its own, but there is nothing warm about the image. Instead, the word “fetus” feels cold and alien. There is nothing pleasant about the bag’s conception.

After much work, the bag is ready to be fitted. The bag maker fastens it around the woman’s neck, sweeping his hand through her hair in a gesture that mimics the intimacy of lovers. The narrator is extremely pleased with his handiwork. He describes the fit of the bag on the woman’s body:

The bag suited her to perfection. The lustrous finish of the leather set off the color of her skin, and its shape fit elegantly along the curve of her breast. The veins and arteries peeking out at the edges, the leather pulsing almost imperceptibly with each contraction, the strap caressing her graceful neck—I had never seen anything like it.

Now, the bag has enveloped the heart, and the bag maker’s admiration for the heart is momentarily supplanted by his admiration for his own creation. In the narrator’s eyes the bag is “perfection.” It not only holds the heart with its “lustrous finish” and “elegant” fit, it sets off the woman’s beauty. Here, we see the bag maker’s desire to touch the heart being carried out by the bag he has made. It molds to “the curve of her breast” and “the strap caress[es] her graceful neck.” The bag maker gains the closeness to the heart he so yearns for through his creation. The bag has become a surrogate for the bag maker himself. There is a breathlessness in the way he explains that he “had never seen anything like it,” an ecstasy expressing the erotic moment. The woman’s reaction, however, lacks enthusiasm. Her comments, in contrast to the bag maker’s perceived “perfection,” point to the bag’s discomfort. She finds “the hole for the artery too high” and complains that “the hooks rub [her] side.” Though she does find the bag “nice and light,” her reaction bears none of the narrator’s fervor.

The bag maker continues to work on the bag. His devotion to the perfection of his creation becomes obsessive. He describes his drive to finish the task he has started:

The bag was almost finished. The leather was a soft cream color, the cutting and stitching were precise down to the millimeter. I had hung a sign on the door announcing that the shop would be closed until further notice and had spent long hours at my worktable. A regular customer had even called to ask me to repair her makeup case, but I turned her away.

The beauty of the heart oppressed me, but my hands were steady as I worked. I had managed to make a thing that no one else could have made.

Again, we see how enamored the bag maker is with his own creation. There is a sumptuousness in the “soft cream color” of the “leather” which insinuates the suppleness of skin. The narrator’s obsessive, meticulous tendencies are seen in the precision of “the cutting and stitching” “down to the millimeter.” His preoccupation with the heart causes him to close the shop and refuse his regular customers. He toils for “long hours at his worktable.” When he explains that “the beauty of the heart oppressed” him, this is already understood because of the description of his compulsion to finish the bag. His obsession with his work is so complete, his only living companion, his pet hamster, dies. Though he says it may have just been old age, he concedes that he may have “neglected him because I was so absorbed in my work.” In the end, however, he asserts that he has “managed to make a thing that no one else could have made.” Here, we see the egoism involved in the narrator’s creation, and also his attachment to the bag. His creation is completely unique. The bag has become an expression of himself, the bag’s sole progenitor. To him, it is perfection.

After the intensity of his work and his throbbing obsession, when the woman ultimately refuses the bag, the blow is unbearable. She informs the narrator that she has found a surgeon who can relocate her heart into the cavity of her chest. She won’t be needing the bag. The bag maker’s response is relayed mostly through dialogue:

“But it’s a wonderful bag. Here, see for yourself. I’ve moved the hole for the artery and switched to smaller hooks. I’m sure you’ll like it.” I held it out for her to see. “I just want to reinforce the stitching here and adjust the strap and it will be done.”

“I’ll pay for it, of course. But I won’t be needing it now. I won’t have anything to put in it.”

“But see how exquisite it is. You won’t find a bag like this anywhere else. The insulation, the breathability, the quality of the materials, the workmanship . . .”

“I said I won’t be needing it.” As she stood to go, she brushed the bag from the table and it lay there on the floor, as still as a dead animal.

Though the bag has become unnecessary to the woman, he tries to convince her of its worth. He offers it to her, holding it out to her, pointing to the alterations he has so carefully made. The narrator’s desperation is evident in the tone of the dialogue. First he insists that it is “wonderful,” and then, when she still rejects it, he presses her to see “how exquisite it is.” He remarks on its uniqueness—she “won’t find a bag like this anywhere else.” He lists the bag’s attributes, ending, frantically, with “the workmanship,” alluding finally to himself. In an ultimate act of dismissal, the woman “brush[es] the bag from the table.” This action, given the narrator’s obsession with the heart and the creation of its bag, is monumentally cold. The severity of the gesture is enforced when the narrator describes the bag on the floor, “as still as a dead animal.” It is as if the woman has killed a part of himself. Here, the bag has become a replacement for the bag maker himself. When the woman rejects the bag, it is the narrator who feels the rejection. It is not just his creation which she sweeps so carelessly to the floor, it is the bag maker she discards as well.

It is this rejection which drives the bag maker’s final actions. He goes to the hospital where the woman is awaiting her surgery. As he waits for the elevator he fantasizes about what he will say to the woman when he sees her:

“Making your bag has been a very important experience for me. I don’t think I’ll ever have the chance to make a piece like this again. Still, I’m happy you’re getting the operation and won’t need the bag. But I do have one final request: I’d like to see it put to its intended use just once. I know it’s asking a lot, but I’d be very grateful. I promise I’ll never bother you again, but nothing is more painful for a craftsman than knowing all his hard work was for nothing. Just this once, I’d be eternally grateful.”

She’ll take off her gown, and I’ll fit it on her.

“Are you satisfied, then?” she’ll ask, eager to be rid of me.

“Thank you,” I’ll say, but when I reach for the bag, I’ll cut her heart away, too.

Rather than see the culmination of the narrator’s revenge, we view his desired actions intimately through his internal fabrications. His detailed premeditation reflects the obsessive personality we have come to know throughout the story. Again he stresses the significance of the creation of the bag, calling it “a very important experience,” and the uniqueness of the bag. When he remarks that “nothing is more painful for a craftsman than knowing all his hard work was for nothing,” the reader may identify with the narrator. We understand better the pain of his rejection. Who does not know the disappointment of working hard for something which eventually comes to nothing? However, the overly polite tone of his rehearsed speech rings false. We sense there is some malfeasance in his request, though we cannot be sure of his intentions. When he reveals his plan to “cut her heart away, too,” we are shocked. The switch in tone from overly polite and cajoling to sharp and starkly violent is stunning. Here, in the end, we realize the extent of the narrator’s dark obsession.

As the narrator awaits the elevator to take him to the correct floor of the hospital, the narration switches to the present tense. The bag maker says: “The bag is in my left pocket. I tried to fold it flat, but there’s a little mound in my pants.” This move into the present tense heightens the suspense of the ending. We are now in the moment with the narrator. The bag in his pocket appears like “a little mound in [his] pants.” Here, the bag is clearly linked to his sexual arousal, physically replacing the narrator’s phallus, emphasizing, in the end, the eroticism of his obsession.

In “Sewing for the Heart,” the narrative relies on two strange objects—the woman’s exposed heart and the narrator’s convoluted bag. Through these objects, we are able to see more clearly the characters of the story. The woman, though reserved and seemingly cold, becomes quite vulnerable when we realize the delicate and precarious placement of her heart. Though the woman exhibits no outward fear of the bag maker or shame toward her condition, the heart itself repeatedly cringes under the gaze of the narrator. It is through the visible heart’s reactions that we begin to suspect the narrator’s intentions, and it is the beauty of the heart itself which attracts the bag maker—not the woman. In the narrator’s detailed evaluation of the heart, we learn of his obsessive nature, his violent yearnings. The creation of the bag enforces these notions of the bag maker. His devotion to the bag is fastidious to the point of madness. The bag takes on life. It becomes a mutated creature born from the narrator. Eventually, it becomes an extension of the narrator himself. Though the bag maker longs to grip the heart, it is his bag which makes physical contact, clinging to and covering the heart.

The relationship between the narrator and the woman, the bag and the heart, becomes one of sexual predation and domination. The bag maker’s violent musings reveal his lust to be predicated on destruction. The bag itself will entrap the heart, cover it, asserting dominance over the pulsing organ. The physical quality of the bag is the perfect representation of the erotic. The bag is empty, waiting to be filled. The erotic yearning itself is based on lack. Desire denotes emptiness and the craving for that which one does not yet possess. The bag can be seen as the physical manifestation of this lack, this erotic urge which drives the entire narrative of “Sewing for the Heart.”

Nine months before my daughter constructed the hot pink cat house, her father died of a fatal drug overdose. At the time of his death, he had not lived with us for over three years. In the last year of his life, he had moved several states away to stay with his mother. My daughter’s relationship with her father consisted of phone calls and video chats and the exchange of thick envelopes of notes and drawings—her father was an artist. Sometimes the communication was frequent. Sometimes there were long periods of silence.

In nearly every conversation they had, they found their way back to the same topic. One day, he was going to build her a house. They discussed the location (faraway mountains), security (a moat like a castle), how many floors it would be, methods for moving from level to level, and various other aspects of the specific design. In the mail, he sent her elaborate blueprints—line drawings in pencil meant to be colored however she saw fit. My daughter spoke of this house often. My daddy is going to build me a house. You can live in it with me. In the house my daddy builds me . . . Even in the long gaps when her father couldn’t be reached, my daughter kept this narrative alive. The story of the house became a mantra, something to hold on to in the absence of his physical presence.

My daughter’s father died, but the narrative of home-building had been embedded within her. When she came home with this strange, radiant, obstinately pink structure, I was overcome with emotion—the nature of which I cannot exactly describe. Hope, maybe. Maybe that was the feeling. My daughter had built her own house. With her own imagination, her own two hands, she had brought this miniature home into existence. Her father was going to build her a house. While that lovely fantasy floated between my daughter and her father, we—she and I—were building our lives, learning together the summit of our own strength. Her father was going to build her a house, but in the end we didn’t need him to, because we had already built it ourselves.

For me, this is the understory of the hot pink cat house. Both the little deer foot lamp and the bag to hold a heart carry with them their own understory, the subtexts of their respective surface narratives. In “Congress,” the deer foot lamp underscores the relationship between humans and nature. It subtly points to the frivolity of our consumerism and our disregard for nonhuman creatures. As Miriam’s source of solace, the lamp also highlights the lack of intimacy within Miriam’s human relationships. Through her attachment to the lamp, we see the failings of her connection with Jack. We see her reaching out for something more than a tepid existence and a lackluster relationship with a man. The lamp is her path to the celestial unknown. In “Sewing for the Heart,” the bag to hold the heart and the heart itself are markers of obsession and desire. The woman’s heart, exposed and vulnerable, is a literal expression of inward sensitivity and unguarded emotions. The woman strives to protect her heart, though her past attempts have failed. Though the purpose of the bag is to keep the heart safe, the narrator’s obsession soon overtakes its primary function. The bag, instead, becomes the bag maker’s way to subsume the heart within his own creation, an extension of himself. The bag maker’s desire is not to help but to dominate, and the bag becomes the instrument of this domination.

Strange objects in fiction allow our inward fascinations to manifest on the page. Like illustrations in a children’s picture book, they reveal what may not be explicitly defined by the text. They serve to illuminate themes and character traits which would otherwise remain hidden. Like fiction itself, these objects are a bridge between the real and unreal. They are a way of grounding the reader in the physical world of the story, even if that world looks nothing like our own. We are captivated by the strangeness of the objects, while, at the same time, we are engaged by their tangibility. Their strangeness grabs our attention, sparks our curiosity, while the physicality of their object-ness holds us firmly. Like an empty bag or a lamp free of expectations, strange objects in fiction are an invitation to imagine and inhabit a new space full of possibility. They are a dazzling reminder of the truth that nothing can happen anywhere.