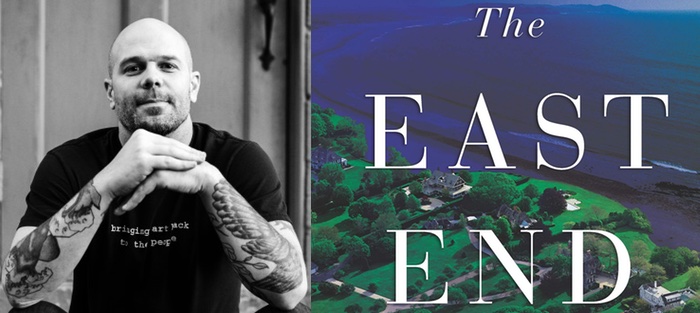

One of the most important lessons we get from reading Jason Allen‘s debut novel, The East End (Park Row/HarperCollins), is that so much of what happens to us depends on perspective.

Corey Halpern, one of the main characters, sees the formidable, barely used, multimillion-dollar estates in the Hamptons where he works sometimes as open spaces, places to break into and explore since their owners leave them largely untouched. His mother, Gina, sees the act of cleaning these homes as a means to an income for her and her sons to survive on. And her billionaire employer, Leo Sheffield, sees his own mansion in South Fork as a refuge for a private meeting, held on the night before Memorial Day weekend begins, before his own family and neighbors will come to intrude on his secrets.

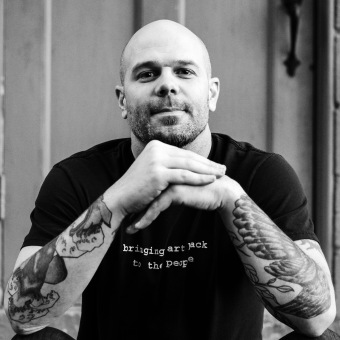

Having once lived and labored for the rich in this world, Allen returns to it as the source material for his first major work of fiction. Late one night this spring, we talked about growing up there, about writing between genres, and about addiction and recovery—both his own and that of his characters.

Interview:

Barrett Bowlin: I know you’ve mined a lot of your experience growing up in the Hamptons for material in the novel, but what were some of the biggest moments you encountered of the class divide there? What stands out to you years later?

Jason Allen: Well, when I was a kid, my mom ended up working at a millionaire family’s summer estate in Southampton. I didn’t realize we were working class until I had more of a comparison with a place like that, where extreme wealth was on display. We had a tiny, two-bedroom house and my mom raised my brother and me on her own for the most part, but the people she worked for had a massive property and a house with something like eight bedrooms, and rooms for specific activities, even a billiard room.

Later, when I was working labor-based jobs in the Hamptons, the traffic itself really highlighted the demographics of the area. Early morning traffic was referred to as the “trade parade” because there were so many work trucks for people who worked various trades. But then in the summer you would see Lamborghinis and Ferraris and the most customized Mercedes, Bentleys, and Rolls-Royces in the mix. I also remember that there was a working-class–poor section of Southampton, which was an area where I had a few friends, and it was within a couple miles of summer homes that were worth in the neighborhood of $20 million. So the class divide always hung in the air for the locals.

Growing up there, as well, what jobs did you find yourself involved in, either working with your mom or while you were out on your own?

Growing up there, as well, what jobs did you find yourself involved in, either working with your mom or while you were out on your own?

I did eventually end up working at that Southampton estate with my mom for one summer when I was nineteen, and that really informed the setting for The East End, but lots of other jobs gave me a fly-on-the-wall POV of the wealthy homes there.

I worked for carpenters, landscapers, and for five seasons I cleaned swimming pools. The pool-guy job sent me to mansions and estates basically unannounced, so I walked into back yards when people were naked or in the midst of blowout fights or just had a chance to overhear hundreds of awkward conversations. I’m grateful now for having had so many strange work days and stories to hold on to afterward. Someday I’d like to write a memoir just about all the jobs I’ve had, especially the one with the pool company.

Having witnessed such a class divide growing up, I imagine it would’ve been very easy for you to caricature the upper-class Hamptonites and property owners in the novel. But I liked it how you were careful to provide such a balance between complex, compassionate characters like Leo versus his demanding, privileged-to-the-core wife, Sheila. What was behind the decision to make Leo one of the book’s protagonists, then?

I’ve been so glad to hear early readers of the novel say that they empathized with Leo, because that was one of the most gratifying surprises during the writing. I didn’t want to create a billionaire character that was a stock villain, but it took some effort to figure out what Leo’s conflict might be that would allow me to care about him. The more I let his character develop, I realized that he’s been in the closet his entire life and has reached a point when he cares enough for his much younger male companion that he brings him to the summer estate the night before Leo’s family and friends are due to arrive for Memorial Day weekend. Leo’s secret life finally crumbles in the most disastrous way, and because other characters arrive as well, unexpectedly, I needed to explore Leo’s panic and the depths of his desperation to try to salvage any semblance of his prior life. I was fascinated to see how far he would go to try to keep his true self hidden, even after a few key people know.

Since telling Leo’s story was definitely part of the overall plan for the book, what was the initial conflict you wanted to set in motion? Who did you start with, and how did those original plans change over the course of writing and revising the novel?

Initially, I thought that the teenage character, Corey, who is a working class kid who breaks into mansions for the thrill, might be the sole POV character, but then I wanted to explore the POV of his mother, Gina, who works at the billionaire’s estate doing the same type of work my mom did. Gina is unlike my mother in every way, other than the job she does, and when we meet her, she’s drinking heavily during the day, taking pills, and has an intense interaction with her soon-to-be ex-husband. Just a bit later, I knew I wanted to get into her boss Leo’s POV. So those three are the main players, but I also found Angelique, Corey’s love interest, really intriguing. Angelique is best friends with the billionaire’s daughter, but she’s not rich herself, which allows for a deeper connection with Corey. She’s the final POV that felt necessary to tell a story with so much emphasis on class, and with so many misunderstandings and overheard snippets of conversations. I had a lot of fun with the complexity and added tension that arose from the shifting perspectives.

For writers like yourself working in multiple genres, what’s the process been like of focusing primarily on one genre for so long and then switching genres?

I’ve found it keeps me from getting burned out on one genre to change over to another from time to time, and they all end up crossing over and informing one another as well. For instance, some of the poems I’ve written are basically slivers of memoir, and some of the memoir chapters I’ve written reinforced my interest in themes of class and addiction, so they’ve then transferred over to some of my fiction. The focus on language in poetry also has become inseparable from the revision process for my prose. On top of all of that, I get a different type of charge from writing through each genre, a different avenue to express a thought or emotion.

Speaking of which, as Corey works through a lot of the experiences you did growing up and living in this world of class disparity, I like it that you’ve included poetry as part of his mechanics. Some readers might know you first as a poet, since you’ve already published both a chapbook and a full book of verse. Not to spoil the ending, but how did you choose to conclude The East End with one of Corey’s poems? (Which is damn beautiful, by the way.)

Thanks so much for saying that about his poem. That took quite a bit of work to get right because I needed to feel that it would be a poem he would write at seventeen. The poem seemed to work well as a moment of resonance to end the story, especially since in my mind Corey is the main character, and the words he’s written in secret, which Angelique gains access to, reveal Corey’s deepest longing, his frustrations, but also that he’s a very sensitive kid. It’s interesting to look back on all the sections through his POV and realize that more of my own experiences and outlooks from when I was his age seeped into his character than I’d planned.

You’ve talked before about addiction and your own path with recovery. With characters like Corey and Gina and Leo in mind, what were your big concerns about portraying addiction here?

For the most part, the characters in The East End all have issues with substance abuse to varying degrees, and even though Gina does attend her first meeting just before the marathon work sessions of Memorial Day weekend, they’re all using alcohol and drugs to cope or to distract from the turmoil of their lives. I wanted to be careful not to push recovery for any of them, but it was gratifying to bring Gina to her first meeting and convey her intense anxiety at the prospect of sobriety, even as she knows she needs to stop drinking.

Leo and Corey have their own paths, and I’d say Corey has a lot of similarities to myself when I was seventeen. All the kids I grew up with smoked and drank a lot and took a whole galaxy of other substances, and that lifestyle carried over for me for many years, but thankfully I got help and have lived a completely different life for quite a while now. I guess I wanted to invite readers to understand addiction a bit more, especially through Gina and Corey, and hopefully some readers who would have had judgments of addicts and alcoholics might open up just a bit more and internalize some empathy.

I think that familiarity with Corey’s situation is what makes him such a complex and compelling character. While you were writing, then, what would you say was the biggest stretch for you in terms of accessing the characters? Who do you think you had the most trouble wrestling with and why?

Well, I’d say Leo was the greatest stretch, but for all the characters I ended up so deep inside their heads that their actions made total sense to me. I’ve had some incredible writing mentors, one of whom, Jack Driscoll, always reminded his students of the importance of empathizing with your characters, no matter how badly they behave, no matter how troubled or flawed. You don’t need to like them all, but you do need to understand them. So you could say I wrestled with the development of each character, but it felt especially gratifying to get to the point of understanding them all, despite their varied backgrounds, conflicts, and motivations.

Along with Driscoll’s advice, what other writing guidelines from mentors or authors you’ve read helped you as you worked on the book?

I’ve been really fortunate to apprentice with lots of amazing author mentors over the years, so I’m sorry to leave anyone out of this answer. The first couple that come to mind are Jack Driscoll and Claire Davis. They each walked me through the process of writing my first novel manuscript while I was in the MFA program at Pacific University. Jack emphasized both character and line-level choices. For example, you want the added effect when you refer to money in certain settings and replace a word like “stack” in the phrase a “stack of bills” to “wad” for a “wad of bills”—that one word change adds a certain seediness that I recall had a potent impact on a scene I’d written in that early novel. Claire Davis was so helpful in walking me through the considerations for the development of setting and scene dynamics. At one point she suggested that I write detailed biographies for my characters, taking into account everything about them that would affect how they act, why they act the way they do. So much of our behavior does come down to the place we live or where we’re from. She also pushed me to read widely, including lots of volumes of poetry, and both she and Jack have a musicality to their prose that I tried my best to emulate, or at least aspired to.

Other mentors, including Jaimee Wriston Colbert and Jack Vernon, whom I worked with during the PhD program at Binghamton University, really helped steer me toward a plot line that was both complex and propulsive.

I’ve had a number of other incredible writing mentors. Each one has contributed to choices I made with this novel, especially during revisions, and I can’t thank them all enough.

The book has these amazing set pieces where the plotting and the action is very kinetic, even cinematic at times. What was the score (or the soundtrack playing in the background) like for you while writing The East End?

I found in recent years that I can’t actually focus on novel pages with any music playing, so I work in silence, but it would be fun to think of what song might be playing in the background of certain scenes. For Corey’s character, we do get to get to ride with him from one break-in to another early on with Iggy Pop and The Stooges playing in his truck, and with Leo we hear Sinatra crooning when he’s in his limo with his young boyfriend, and Gina listens to classic rock radio when she’s drinking alone and high on pills, so it varies a lot from one character’s POV to the next. The weekend parties also include classical music that’s played by live orchestra musicians. Still, since I’m such a huge fan of Tom Waits, it’s likely that some of his songs were in my head as I wrote. More than likely in the scenes with the most drinking.