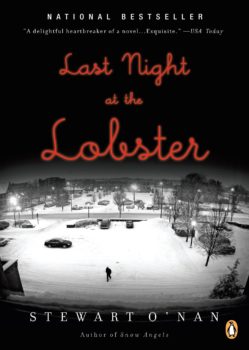

It’s no coincidence that the first words of John Updike’s “A&P” describe physical movement: “In walk these three girls in nothing but bathing suits.” In works of fiction that are limited to a single location, as Updike’s story is, the constraints of setting apply pressure to the narrative, a pressure that results in the movements of the characters within such confined spaces becoming particularly resonant, perhaps even more so than the movements of characters in other stories who are freer to roam the world at large. The “trapped in a snow-globe” atmospheres of both “A&P” and Last Night at the Lobster by Stewart O’Nan are created by such closed-worlds settings, the grocery store and the Red Lobster respectively, and the limitations of these single locations makes the staging within these worlds even more meaningful. After all, when there are few places to physically go in a story, every movement counts.

Because both O’Nan and Updike feature main characters in a single location facing a crisis on their last day of work, and because both characters are, for the most part, tethered to their location (to say nothing of the women they share these locations with), there are obvious comparisons to be drawn between the two. But rather than concentrate on the similarities that can be drawn between these two works, it is perhaps more helpful to examine the differences between the ways the two characters perceive their immediate surroundings, and specifically how their differing perceptions of their own locations reflect their feelings of place and belonging in their own lives. Both Updike and O’Nan utilize the limited space of the story to reflect their main characters’ frames of mind. The location, and the character’s relationship to it, provides a means through which to read the interiority of the two men, though, as we will see, their limitations affect them in vastly different ways. The stories revolve around the two different characters, but the characters also revolve around the two similar settings and, because of the strict constraints of each setting, location and characterization are inexorably interrelated.

In a sense, Sammy from “A&P” and Manny from Last Night at the Lobster are both trapped in their locations, and by extension, in their own lives. Sammy is stuck at a job that he hates, but one for which, it is implied, his family and community believes he should be grateful. Manny, on the other hand, knows that most of the world views him as the captain of a failing ship. Though the Red Lobster that he manages is slated to shutter it doors when the story begins, he feels compelled by a sense of duty to allow one final lunch and dinner service to take place during a winter snowstorm. Though this decision is in no small part due to the fact that it will be the last time that he will likely ever see the woman he is in love with, Jacquie, a waitress who has recently broken off a fling with him, he also feels genuine affection for the restaurant, despite the fact that he recognizes that it is an affection that is neither reciprocated by the corporate entity that owns Red Lobster, nor entirely comprehensible to his peers. In a world of people who see “the Lobster” as just a job, Manny knows that he in the minority by seeing the job as his life. When imagining a fellow employee away from the restaurant, Manny reflects that “away from the Lobster he comes to life.” For Manny, though, the opposite is true; it is as though he feels most alive when he is within the confines of the restaurant’s walls.

In a sense, Sammy from “A&P” and Manny from Last Night at the Lobster are both trapped in their locations, and by extension, in their own lives. Sammy is stuck at a job that he hates, but one for which, it is implied, his family and community believes he should be grateful. Manny, on the other hand, knows that most of the world views him as the captain of a failing ship. Though the Red Lobster that he manages is slated to shutter it doors when the story begins, he feels compelled by a sense of duty to allow one final lunch and dinner service to take place during a winter snowstorm. Though this decision is in no small part due to the fact that it will be the last time that he will likely ever see the woman he is in love with, Jacquie, a waitress who has recently broken off a fling with him, he also feels genuine affection for the restaurant, despite the fact that he recognizes that it is an affection that is neither reciprocated by the corporate entity that owns Red Lobster, nor entirely comprehensible to his peers. In a world of people who see “the Lobster” as just a job, Manny knows that he in the minority by seeing the job as his life. When imagining a fellow employee away from the restaurant, Manny reflects that “away from the Lobster he comes to life.” For Manny, though, the opposite is true; it is as though he feels most alive when he is within the confines of the restaurant’s walls.

Despite their differing stances toward their jobs, Sammy’s begrudging attitude toward the store he hates and Manny’s appreciative attitude toward the restaurant he’s losing, neither man is free at the onset to do as he likes. Additionally, there is a socioeconomic pressure both men suffer that is also related to their location. Both men are working class and have few other options for work, thus limiting their ability to move in their lives, as well as in their careers. Sammy’s economic class is actually defined by location within the story: “our town is five miles from a beach, with a big summer colony out on the Point, but we’re right in the middle of town. . . . It’s not as if we’re on the Cape; we’re north of Boston and there’s people in this town haven’t seen the ocean for twenty years.” This specific detail of place reveals that Sammy knows that his future is dictated by his distance from, rather than proximity to, the beach. Though at work he frequently gets to interact with members of that beach colony, most notably the girls in bathing suits that inspire him to do the “heroic” deed at the end of the story, he is never permitted to become one of them. In explaining the distance from the town to the beach, Sammy is admitting that, deep down, he knows his place, and that, in a sense, place is the crux of all the problems in his life. Not only is he physically stuck in the A&P day after day, (and for the entire story, save the last paragraph), but he is also stuck in the larger sense in his working-class existence. The circumstances of his family’s place in the world are what really limit his movement in the story, far more than the physical borders of the grocery store. In the world of the story, being stuck on the wrong side of the tracks means being stuck in life. In this way Updike cleverly stages his story in such a way that no matter how much Sammy yearns for mobility, he cannot move from his station.

Like Sammy, Manny is also from a working-class background, not college-educated, and with limited job prospects outside of the Red Lobster conglomerate. But where Sammy bristles at the limitations that have been set for him in his life and his job, Manny embraces the way his life revolves around the Red Lobster. The idea of being cut loose from the setting in which so much of his identity is wrapped is almost unbearable to him. Manny’s world, though limited in many of the same ways as Sammy’s, is not a place that he wants to escape from, but into. The restaurant gives a sense of purpose to his days that allows him to remain passive in his own existence, settling into a life that he doesn’t necessarily want with a woman he isn’t in love with because he lacks the confidence to make a dramatic move toward something better. The restaurant is his crutch, and moreover, it carries for him associations with the best, most vibrant times of his life, the period during which he had a relationship with Jacquie. Whereas Sammy longs to break free of his constraints, Manny is afraid to.

Consider the differences between how these two characters describe their locations. Sammy paints a picture of the grocery store as a harsh and unappealing mishmash of useless items, of “light bulbs, records at discount of the Caribbean Six or Tony Martin Sings or some such gunk you wonder they waste the wax on, sixpacks of candy bars, and plastic toys done up in cellophane that fall apart when a kid looks at them anyway.” Even worse, the place is populated by “women with six children and varicose veins mapping their legs” and folks like the “old party in baggy gray pants who stumbles up with four giant cans of pineapple juice.” Without the presence of a group of teenage girls in bathing suits, Queenie and her friends, the place holds absolutely no appeal to Sammy and because of that, their sudden appearance on the scene is able to affect him so strongly. He knows all too well how depressing the store is without the girls in it, so when they appear, and subsequently disappear, he finds their loss so unbearable that he is compelled to follow them out of the store.

On the other hand, Manny experiences his surroundings in a markedly different way. He feels genuine affection for his restaurant, and that affection is evident in the lyricism that is used to describe what might, to anyone else, be dismissed as a prosaic scene, a glimpse inside a Red Lobster off the side of a busy highway:

[Manny] tramps out to the end of one wing where Dom’s and Roz’s cars sit in exile and works back toward the Lobster, the illusory movement of the colored string through the front doors and the glow from the windows and the candlelit faces of people eating inside all suddenly, surprisingly, beautiful to him, as if he’s still stoned. He rests for a moment to appreciate the vision and hears, in the hush, at a distance, the frantic whizzing of a car spinning its wheels. In the storm light, the restaurant looks warm and alive and welcoming, a place anyone would want to go. It looks like a painting, and he feels proud, as if this is his work, and in a way it is, except it’s over, like him and Jacquie, lost, gone forever. Is that why he loves it so much?

In this passage, not only is O’Nan painting a picture of beauty in the mundane by likening the restaurant to an actual piece of artwork with the painting analogy, but the long, lyrical sentences are a direct result of Manny’s sentimentality toward the location and the memories that it harbors. While Sammy’s location is described in crude, unattractive terms because of Sammy’s resentment, Manny’s location is described lyrically and beautifully because it is informed by beautiful associations. In both works, the writers use the location, and the people staged within it, as a window to the psyche of the character. The loathing and adoration coming through the language are not born of the physical traits of the limited settings alone, but the characters’ willingness to accept those limitations. “Gunk” and “wasted wax” represent resentment on Sammy’s part, while Manny’s “painting” is a manifestation of his preemptive nostalgia towards the place and by extension, the relationship that has ended.

In addition to revealing character interiority through setting description, Updike and O’Nan also stage their scenes with specific movements that reflect the mindset of their characters while also keeping their stories from feeling too stifled by their constraints. When a story takes place almost entirely in an A&P, or a Red Lobster (save one lunch-break trip across the parking lot to the mall and the gas station), it is important to find ways to allow the constraints of the single setting to apply narrative pressure without resulting in claustrophobia, or boredom, on the reader’s part. After all, lingering overlong in any one location may make a story stagnate. But Updike and O’Nan circumvent this problem by using specific language designed to break up the monotony of the setting.

In “A&P” we see this right from the outset with all the prepositions that Sammy uses to describe the girls’ arrival in the first paragraph: “In walks these three girls. . . . I’m in the third checkout slot, with my back to the door, so I don’t see them until they’re over by the bread.” Later he continues with very specific language describing all the girls’ movements: “the girls had circled around the bread and were coming back, without a pushcart, back my way along the counters, in the aisle between the checkouts and the Special bins.” And even when Sammy doesn’t rely on prepositions to give the reader the blow by blow of the girls’ appearance, he uses very specific details to narrate their passage through the store: “they all three of them went up the cat-and-dog-food-breakfast-cereal-macaroni-rice-raisins-seasonsings-spreads-spaghetti-soft-drinks-crackers-and-cookies aisle. From the third slot I look straight up to the meat counter and I watched them all the way.” The result of these hyperspecific details and the constant locating of the girls within the space of the store via prepositions gives the scene a sense of movement and urgency, despite the limitations of its location, while also emphasizing Sammy’s infatuation with the girls.

Through parts of speech, Updike has Sammy dramatize his surroundings, allowing his imagination to be stimulated by the arrival of the girls and underscoring, not only how much their presence in the store is a seismic shift for Sammy in terms of his perception of the limitations of his own working-class life, but how starved for stimulation he has been in the mind-numbing confines of the store before their arrival. Now that the girls have arrived, the store holds more interest to Sammy just because of their presence in it. “The whole store was like a pinball machine and I didn’t know which tunnel they’d come out,” says Sammy and we get the sense with this metaphor of how powerfully the girls have affected him. They have brought the excitement of an arcade to a place that, in Sammy’s mind, is usually reserved for customers that he refers to as “sheep.” Moreover, the “sheep” also react to the girls, albeit in a markedly different way than Sammy does: “The sheep pushing their carts down the aisles—the girls were walking against the usual traffic (not that there were one way signs or anything)—were pretty hilarious. You could see them . . . kind of jerk, or hop, or hiccup, but their eyes snapped back to their own baskets and on they pushed.” We get the sense through lively description, plentiful prepositions and metaphors of the pinball games and the barnyard creatures, that Sammy is spurred on by the arrival of the girls to do exactly the same thing in his narrative that he claims Queenie is doing in her walk through the A&P, that is, “putting a little deliberate extra action to it.”

O’Nan also uses descriptive language to push against the constraints of a mundane location via metaphor. Though unlike Sammy, whose default mode, outside of the presence of the girls, is to describe the store as an unexciting place, Manny constantly likens the Red Lobster to more dramatic locations, which not only creates a little breadth in the story for the reader by opening it up to other locales via this figurative language, but also emphasizes how much bigger the Lobster is in Manny’s life than just his workplace. When he opens the restaurant in the morning, it’s not just an empty store, but a place that is “as dark as a mine.” When the cook line is up and running, Manny likens the kitchen to a “tropical climate.” Manny even compares himself to a “cop writing someone a ticket” when he’s keeping tabs on his employees. These comparisons make the closed space of the story come alive for the reader, yes, but they also reveal how Manny perceives the space. The Red Lobster is not only his world but also the world to him, as he can travel from mines to tropical rainforests when he’s there. He can play at being a cop, or even a director of a lavish theatre production: “[He] turns up the house lights . . . dials the house music to the approved volume, and . . . tugs the cord to the blinds. On cue, Mr. Kashynski hauls himself out of his car and starts up the walk.” O’Nan describes Manny’s actions here so theatrically because Manny sees his job as theatrical. He has convinced himself that this, the Red Lobster, is all the world he needs, despite the fact that that the curtain is about to fall on that world forever.

O’Nan also uses descriptive language to push against the constraints of a mundane location via metaphor. Though unlike Sammy, whose default mode, outside of the presence of the girls, is to describe the store as an unexciting place, Manny constantly likens the Red Lobster to more dramatic locations, which not only creates a little breadth in the story for the reader by opening it up to other locales via this figurative language, but also emphasizes how much bigger the Lobster is in Manny’s life than just his workplace. When he opens the restaurant in the morning, it’s not just an empty store, but a place that is “as dark as a mine.” When the cook line is up and running, Manny likens the kitchen to a “tropical climate.” Manny even compares himself to a “cop writing someone a ticket” when he’s keeping tabs on his employees. These comparisons make the closed space of the story come alive for the reader, yes, but they also reveal how Manny perceives the space. The Red Lobster is not only his world but also the world to him, as he can travel from mines to tropical rainforests when he’s there. He can play at being a cop, or even a director of a lavish theatre production: “[He] turns up the house lights . . . dials the house music to the approved volume, and . . . tugs the cord to the blinds. On cue, Mr. Kashynski hauls himself out of his car and starts up the walk.” O’Nan describes Manny’s actions here so theatrically because Manny sees his job as theatrical. He has convinced himself that this, the Red Lobster, is all the world he needs, despite the fact that that the curtain is about to fall on that world forever.

Whereas Updike conveys Sammy’s relationship to his setting through his prepositions, O’Nan uses lively verbs to describe Manny’s movements throughout the space: “Manny strides to the far end of the bar, dips his hip at the corner, then squares, stutter-steps, and shoulders through the swinging door” (italics mine). In fact, in “A&P” these kinds of extravagant movements are reserved, not for Sammy, who is stationary in his cashier lane, but for the girls he is so infatuated with. In Sammy’s description, it is not himself but the girls who are constantly moving, not only as they physically transverse the store, but even as they revel in the very act of being young and alive. We’re told that the bathing suits the girls wear have “slipped” and their shoulders have “looped loose.” A few sentences later, we’re told that the hair of Queenie is “done up in a bun that is unraveling” and that her neck is “kind of stretched.” Sammy is attracted, it seems, not just to the girls’ bodies, but to how uncontained they are in their clothing. The freedom afforded by their socioeconomic status at the beach colony is evidenced not just by impertinently wearing bathing suits at the A&P, but by the way every part of their bodies seems to have the freedom to move around, to “stretch” out and “loosen.” The girls literally can’t be still, as even when they are not moving, Sammy perceives them as bursting with unfettered life.

It’s heart-breakingly ironic, then, when the reader realizes that even while Sammy calls the rest of the customers “sheep,” he himself is also in a pen, stuck where he is behind the register. The girls may have inspired him to finally move from his place in the end, but when he does, he is not rewarded for it. The girls disappear before he ever gets a chance to catch up with them, having harnessed that limitless movement that they are blessed with to literally move away from him: “The girls, and who’d blame them, are in a hurry to get out, so I say ‘I quit’ to Lengel quick enough for them to hear, hoping they’ll stop and watch me, their unsuspected hero. They keep right on going, into the electric eye; the door flies open and they flicker across the lot to their car.” Sammy, who up until this point has failed to realize that he is just as domesticated and penned in as the customers he so detests, cannot match the girls’ movements and because of that, they slip away from him.

It is also no coincidence that Sammy’s epiphany at the end of the story, the moment after he quits and realizes the magnitude of his gesture, happens only after he moves away from his spot behind the register to the world outside the store. Once he literally moves, the first and only time in the story that he steps away from his place behind the register, he comes to realize “how hard the world was going to be . . . hereafter.” Sammy recognizes this difficulty because he realizes that he doesn’t have the social movement of the girls and that in a sense, he will always be on the outside looking in to the life that he wants so badly to be a part of. Whereas when Manny looks into his restaurant from outside and sees a thing of beauty that is about to be taken away from him, Sammy looks in and sees only the inescapable drudgery of the rest of his life. Both authors move their main characters outside of the setting but to vastly different ends because of the differences in the aspirations and the interior lives of the two characters.

Both “A&P” and Last Night at the Lobster give the minute attention to detail that is necessary for works that are self-contained like this because these details help create a sense of movement within these limited locations that helps fend off the possible stagnation of spending too much time locked in one setting. Metaphor and vibrant parts of speech keeps the stories moving so that the A&P and Red Lobster become places that the reader gladly commits to spending so much time in, though how the reader perceives the constraints of these surroundings is directly influenced by how the main characters see, not only their locations, but themselves. If fiction holds a mirror up to human nature, in “A&P” and Last Night at the Lobster, Updike and O’Nan also hold the mirror up to the characters themselves and the reflection spills out onto the stages that they have created. The location not only gives these stories their life, but reflects the lives that they contain.