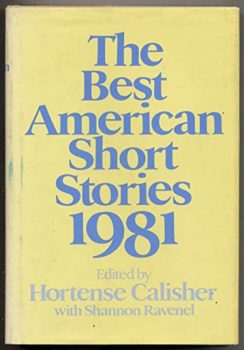

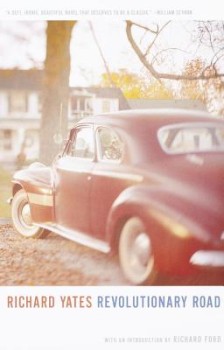

Lonni stood in the middle of the brightly lit dining area of Boston’s Crossroads, or ‘Roads’ as everyone called it. She said, “The thing you gotta know about Mr. Yates besides that he’s a famous novelist is he comes down twice a day, sits in the same booth, orders the same thing – a burger and several,” she gave a wink, “pints of Guinness.” I squinted. Although a part of me wanted to be a writer, I had no idea who Richard Yates was. None of his books had made my reading lists at Boston University. “Start with Revolutionary Road, Lonni said, “It’s a classic.”

Lonni stood in the middle of the brightly lit dining area of Boston’s Crossroads, or ‘Roads’ as everyone called it. She said, “The thing you gotta know about Mr. Yates besides that he’s a famous novelist is he comes down twice a day, sits in the same booth, orders the same thing – a burger and several,” she gave a wink, “pints of Guinness.” I squinted. Although a part of me wanted to be a writer, I had no idea who Richard Yates was. None of his books had made my reading lists at Boston University. “Start with Revolutionary Road, Lonni said, “It’s a classic.”

She gave me a green apron with a shamrock on the pocket, unlocked the front door and sent me out onto the floor. I watched her calmly sail up and down the aisle, every order smooth and successful, while I raced around forgetting items and losing checks. By two o’clock, the lunch rush was over and the dining area empty. It was into this sudden quiet that a lone customer, tall and mumbling, a cigarette hanging from his bottom lip, made his way into the bar.

Lonni signaled and I gathered this was the famous novelist. Yates was just folding himself into the far corner booth when we arrived. Gaunt, with unkempt hair and a wild, overgrown beard, his rumpled shirt and tweed suit jacket smelled as if they hadn’t been cleaned in weeks making Yates look more like a homeless person than a respected writer. I was shocked.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Yates,” Lonni chirped. “I’d like to introduce you to our new waitress, Leslie.” Yates gave me a sideways glance. That’s when I noticed his lower lip. Unlike the rest of his narrow body, it was voluptuous and full, like a woman’s. “Are we ordering the usual, sir?” Lonni asked. Yates nodded and the two of us sped toward the kitchen, placed the order and swung by the bar to pick up his beer. By the time we arrived at his booth, the table was littered with the soft snow of cigarette ash and the air filled with his deep, labored coughs.

Each time Yates shuffled into Roads that summer, I avoided making eye contact. Why didn’t he get help, join AA? My aversion may have been due to a grandparent who seemed to drink too much. Or maybe it came from my teen years when I watched my mother suffer protracted chemotherapy and radiation treatments: she too had entered rooms haggard and weary. Maybe it was just too painful to witness Yates in decay. Whatever the reason, I judged him.

I knew nothing about Yates’ rootless upbringing, his father’s desertion, his stints in sanatoriums or endless battles to quit drinking. I presumed he went to readings or taught a class nearby but couldn’t really picture him out in the world. I pledged that if I ever did become a writer I wouldn’t turn out like Richard Yates.

Sometimes, while I scurried around I glimpsed Lonni and Yates laughing and talking. He sat hunched, waving a cigarette, his face animated. Were they discussing his books? His life? A part of me wished I could talk to him that way too, wished I could stop by and chat with him about the literary world. But what could I say? I couldn’t ask about his books because I hadn’t read them. I couldn’t tell him about my journals—weighed down with the sorrow of losing my mother or my angst-filled attraction to girls—what I did wasn’t writing. Real stories had characters and plots. My words were more like tiny life preservers.

When fall classes started, I cut back my hours at the bar and saw Yates only when he ventured into Roads for supper. It was an incongruous sight: Friday night packed with boisterous college students, everyone laughing and ordering pitchers of draft beer and large cheese pies and in the midst of it, Yates, smoking his ever-present cigarette. We were both outsiders then. He sat looking depressed and isolated, slumped in his booth, while I watched the straight college students flirt and laugh from my own lonely perch at the wait station. It softened me to see his vulnerability and to feel my own. So every half hour, when he signaled another round without looking up, I delivered it without judgment. He unfolded himself from the booth around midnight and made his way upstairs.

We both left the bar at the end of the year. I graduated and Yates left Boston to teach at the University of Southern California. Once there, he recreated his Boston life with one huge exception: he had quit alcohol. “I was much more affable when I was drinking,” he said in an interview. “Now, I’m sort of shrunk into myself from the effort to keep from drinking.”

Richard Yates passed away three years later in 1992 but I didn’t hear about it. I was busy coming out, working on my grief with a therapist, and sending poems and essays to journals. It was scary and exciting to send my words into the world but each time I received a rejection slip, I wanted to quit the whole enterprise. This business of trying to be a published writer seemed like a peculiar type of masochism. Still, the personal side of writing never disappointed me. Each time I opened my journal, my pen led me to a clear, open space within myself. I wondered if these two aspects of writing would ever come together – the deeply personal and the public. While I continued to collect rejection slips, Yates stayed in the back of my mind, climbing the stairs to and from his desk above Roads, the kind of writer I still didn’t want to be.

Richard Yates passed away three years later in 1992 but I didn’t hear about it. I was busy coming out, working on my grief with a therapist, and sending poems and essays to journals. It was scary and exciting to send my words into the world but each time I received a rejection slip, I wanted to quit the whole enterprise. This business of trying to be a published writer seemed like a peculiar type of masochism. Still, the personal side of writing never disappointed me. Each time I opened my journal, my pen led me to a clear, open space within myself. I wondered if these two aspects of writing would ever come together – the deeply personal and the public. While I continued to collect rejection slips, Yates stayed in the back of my mind, climbing the stairs to and from his desk above Roads, the kind of writer I still didn’t want to be.

By 2008, sixteen years later, I had met my partner, moved to California, and experienced a few modest successes as a writer. Still, not a day passed that I didn’t question my decision to write. Then one morning I came across a movie review for Revolutionary Road. The article included a sepia-toned photograph of Yates looking exactly the way I remembered – thick beard, wild hair. I saw the movie and afterward bought the book, but the story felt too heavy and sad and I put it down, unfinished. Nevertheless, Yates kept haunting me. Two decades had passed since my days at Roads, but he hadn’t faded from my mind. Why was that? I did then, what I always do when something or someone confounds me – I opened my journal and wrote. I sat down to sort Yates out, got only so far and set it aside.

The next year, after the elation of finding an agent for a book I had spent five years writing, I was told there were no offers to buy my manuscript. This time I was really through with writing. Months passed before once again, something called me back. In bed with the flu, I opened my laptop and wrote out the story of how I first learned my father worked for the CIA. I sent it to the Los Angeles Times and was flabbergasted and grateful when they accepted it.

In the same way I felt called to write that essay, I was drawn back to the one about Yates but soon realized I would never get anywhere unless I followed Lonni’s long-ago advice and finished reading Revolutionary Road. I went to the bookshelf in our living room and pulled it out.

I thought I knew what I would find: a sad, sharp dismantling of 1950s America told in startlingly honest prose. But what I didn’t know was that I would actually like it and that it would change me. When April told Frank about her plan to salvage their empty suburban lives by moving to Paris, my heart lifted. I really, really wanted them to take the chance, if nothing else, to at least take a stab at living chosen, wanted lives. My 20s and 30s had seen me struggling toward this as a writer and person, and for me, it had been worth it. Just as finally reading Revolutionary Road had been worth it. It is a moving story, as complex as Yates the man—as complex as all of us.

If Yates were still alive, I would tell him his book is beautiful and sad. I would say I knew him when I was young and hurting, that I judged him then but that I had learned better.

Now, as I climb the stairs to the rehabbed garage where I write each morning, I think of Yates. I see him face the blank page and instead of worrying about whether editors would embrace and publish his work or what the sales of his next book would be, I imagine him preoccupied with getting the words on the page as close as he could to the perfection of his ideas. Most of all, I realize what I couldn’t see, at twenty-one, that as I watched him come and go from the bar I was witnessing what it takes – the dedication, heart, and humility necessary to do what he himself once described as, “the hardest and loneliest profession in the world, this crazy, obsessive business of trying to be a good writer.”

And that is exactly the kind of writer I hope to be.

Links & Resources

- More essays and posts about writers “Under the Influence”

- Stewart O’Nan’s thoughtful piece for the Boston Review (Oct/Nov 1999), “The Lost World of Richard Yates: How the great writer of the Age of Anxiety disappeared from print” –before the renaissance of the writer’s work.