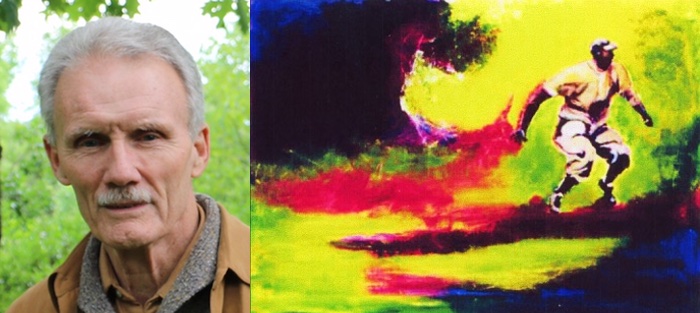

When I came to study in Cornell’s MFA program in the late summer of 1985, I did not know of the generosity of its faculty writers, Stephanie Vaughn and Lamar Herrin. I had never met either of them, and at the same pre-semester party where I was to meet my future wife, at the novelist Alison Lurie’s house, I met Lamar Herrin.

He was a tall, strikingly handsome man, and why shouldn’t he be? Decades earlier, in his very early twenties, he’d had bit parts in Hollywood movies with Elvis, Peter Lorrie, Frankie Avalon. Lamar, I’d soon learn, was as bright and generous and uncommonly decent, and as large-hearted and exacting a novelist, as he was handsome.

He would, of course, cringe to hear such things said about him. Just as he cringed at the world of Hollywood, and fled that shiny place in the second year of a five-year contract. All, God help us, to write literary novels.

From book to book over the past three decades, Lamar Herrin has explored the fault lines of American life, the fractures left by the 1960s, the American and Spanish civil wars, and more than anything, perhaps, he has returned again and again, as he does in his most recent novel, Father Figure (Fomite Press), to what might be the great subject of literature—from the Iliad to Oedipus to Lear to Karamozov. Parents and their children. More specifically, to fathers and sons.

Lamar Herrin and I sat down on an unusually warm fall afternoon in Ithaca, as the leaves were just beginning to turn, to talk about Father Figure.

Interview:

Paul Cody: I know you don’t want to be labeled a Southern writer, but the fact is that up until your last three books your stories and novels were almost all located in the South. Your previous novel, Fractures (Thomas Dunne Books, 2013), was set, it seemed, in upstate New York. Before that you wrote two books: the novel House of the Deaf (Unbridled Books, 2006) and the memoir Romancing Spain (Unbridled Books, 2006). Now in this last novel, Father Figure, you’re squarely back in the South. Does it make any sense pursuing this line of inquiry or should we immediately go on to something else?

Lamar Herrin: We can pursue it without belaboring it, I hope. I’ve lived in Ithaca New York since 1977, but until I wrote Fractures (which deals with a family’s decision of whether to lease their land for hydrofracking or not, and the character-revealing tensions that decision gives rise to), I had not set anything hereabouts. Off and on I’ve spent a number of years in Spain (marrying a Spaniard, fathering a son there), but with the exception of a few stories had never dealt with that land, that country, in the way in which novels force you to immerse yourself in a place. A sense of place is important, is essential, in any novel, but I suppose Southern writers are more affected by that than most others. Why? Someone like Faulkner, better yet, someone like Quentin Compson, puts himself in a position to be haunted and out of that hauntedness spins fabulous tales. The Compson-like narrators immerse themselves in all that flowery decay (honeysuckle in Sound and the Fury, wisteria in Absalom, Absalom!) and suffer the consequences. Ike McCaslin, too. Paradise lost? Followed by the flower-proof Snopes? I do think a number of Southern writers look for all the drama they can get out of their land. And I do think they have a strong sense of history. That is, they tend to personalize history precisely because they take it so personally. And since history begins at home, family history in the South (and in Southern literature) tends to outweigh history on the world’s high stage, which it might mimic. And it all, of course, begs to be celebrated in the act of being lost, so language is frequently taken to the limit (the young Kentucky writer C.E. Morgan seems to write that way). All of which affects me strongly, and I’m sure can be found in my work (and which makes me long to be able to write with the lyrical economy of, say, James Salter), so in that sense, I suppose, Father Figure does represent a coming home.

And the patriarchal figure, he’s kind of a mainstay, too, in Southern fiction. You’ve got a helluva patriarch in this novel, a Battle of the Bulge casualty, one-legged and stomping around, although on a crutch, like a vengeance-mad Ahab, determined to take it out on anybody who crosses his path. The difference is that before the war he was the town’s fair-haired boy and everybody loved him, including his beautiful wife. He was a four-letter man. I wonder, by the way, if contemporary readers, of the younger set, will know what a four-letter man is. Everything is so specialized now. Parents coaching their children practically from infancy on to be billionaire football and baseball players, golfers, tennis players, and so on.

And the patriarchal figure, he’s kind of a mainstay, too, in Southern fiction. You’ve got a helluva patriarch in this novel, a Battle of the Bulge casualty, one-legged and stomping around, although on a crutch, like a vengeance-mad Ahab, determined to take it out on anybody who crosses his path. The difference is that before the war he was the town’s fair-haired boy and everybody loved him, including his beautiful wife. He was a four-letter man. I wonder, by the way, if contemporary readers, of the younger set, will know what a four-letter man is. Everything is so specialized now. Parents coaching their children practically from infancy on to be billionaire football and baseball players, golfers, tennis players, and so on.

A bygone age, which the narrator, the patriarch’s son, is fully aware of. Yet that same son can’t give up on a father he never knew, the pre-war hero of the town, its golden boy, about whom he’s heard countless stories, about his mother too, but these stories in almost no way correspond to the post-war parents, the post-war casualties, he knows. The germ of this novel, by the way, came from a story I published in Epoch magazine nearly twenty years ago, entitled “Casualties.” It was a story of that hero turned into an avenging, acquisitive force, but I guess I always felt the story belonged more to the narrating son than it did to his father. I remembered a quote from the Odyssey, which I went back and found (and now serves as the novel’s epigraph). It’s Odysseus talking to Telemachus: “No god. Why take me for a god? No, no. / I am that father whom your boyhood lacked /And suffered pain for lack of. I am he.” I may be a little off on my own chronology, but when I went back and found that quote I began to realize the story belonged to the son, whose pardon Odysseus begs, not to the heroic father, and that the story deserved to become a novel.

Wow! That’s some quote! I don’t know how many times I was sure somebody had said something in some book, then when you go back and look for it you almost never find it. Turns out those are lines or speeches we, the readers, have written in ourselves. That used to frustrate the hell out of me until I began to see it all as one ever-enlarging, ever-evolving book that an author gets started but that readers keep adding to. I guess the good books—the great books—are the ones that invite those sorts of additions, interpolations.

Except in this case it was there on the page. Odysseus, after all his adventuring, all his philandering, and about to enter into all that slaughtering of the suitors, pauses long enough to apologize to his son. It may be one of the most tender moments in all of literature. It certainly cements the allegiance of Telemachus. And I think all of that had something to do with the ongoing inspiration for my novel. Those brief luminous moments that last a lifetime and determine a relationship, a state of allegiance and trust.

For instance, in Father Figure, one of the narrator Jay Langley’s first memories, maybe the first, is of his one-legged father picking him up off the floor and setting him down beside him in an easy chair. Jay goes on to narrate:

. . .and there is nothing spooky about it, nothing to be kept out of sight—as though in darkness at the back of a store—and I remember in that instant it being the most natural fit in the world. My father lost a leg fighting for his country, and I sit there in the space provided making up the difference.

The store is a family furniture store that Bob Langley will briefly sell used furniture out of the shadowy back reaches of, and his son Jay will live the rest of his life in the glow of that memory and a handful of others. When the time comes to account for his father’s wounding in the Battle of the Bulge and to join him in that freezing cow pasture in the Ardennes, he won’t hesitate, even if his own sanity is at stake. Because his father picked him up and set him down in “that space provided?” Yes, probably so. It was probably the lastingness of that first memory—certainly one of the first—and the volumes it spoke that set him on the course that his life and the novel itself would take. But you never know, do you, Paul? I don’t know about you, but I’ve always felt when my characters surprise me, and take the plot of the novel in unforeseen directions, that those are the moments when the book comes alive, precisely the moments when you the author seem to have the least say-so over it.

But you’re out on a fine edge then, and maybe risking your sanity in the process. What did Melville tell Hawthorne? That he’d written an evil book (or was it an insane one?) and come out on the side of the angels? Something like that. Well, it took Queequeg’s coffin to save him from falling under Ahab’s spell himself. I wonder if Melville saw that ending, that coffin bobbing up like a buoy, all the way? Or if at the last moment he just grabbed hold? Now, there would be a great project! Choose your favorite ten novels and ask the authors if they saw the ending coming all the way. Or were they out adventuring themselves?

John Irving once told me that he had to write the last chapter of his novels first, otherwise he felt too anxiously adrift to carry on. This was not too long after he’d published The World According to Garp. I said, “You mean you block it out, don’t you? And he said, “No, I mean I write it down word for word.” So much changes during the writing of a novel, so many characters come on stage demanding their say, that I couldn’t believe he was being serious, but he insisted he was. Every word.

John Irving once told me that he had to write the last chapter of his novels first, otherwise he felt too anxiously adrift to carry on. This was not too long after he’d published The World According to Garp. I said, “You mean you block it out, don’t you? And he said, “No, I mean I write it down word for word.” So much changes during the writing of a novel, so many characters come on stage demanding their say, that I couldn’t believe he was being serious, but he insisted he was. Every word.

How did we ever get lured into this profession of endless guesswork?

William Gass said that great art shames us with its superior reality, or words to that effect.

So we try to create gods of our own—and holy texts—to worship?

We’re getting pretty far afield here. Especially when you consider we’ve made the bulk of our living as teachers. As if there were a right and a wrong way to go about writing fiction and here’s how you stay on track. I’ve always felt a queasiness in my stomach when I implied such a thing, and I always felt my students weren’t getting their money’s worth when I began to go inspirational on them. One year about midway through my twenty-nine years at Cornell, I audited Astronomy 101, followed the next semester by Geology 101. I did all the reading and the labs (just didn’t take the exams). I learned a lot, and was awfully glad I audited those courses, but I also remember coming out of class and going off to teach classes of my own overcome by envy. My astronomy and geology professors had a body of knowledge to pass on and I had. . .what? My urges, my doubts, my hunches, my sensibilities?

Could we come back to your book, please?

We should. Although after quoting what Melville, John Irving, and William Gass have had to say, that might be a bit of a downer.

All right. Here’s a question, maybe the key question as far as I’m concerned. Father Figure is not a long book as novels go, but it’s painted on a broad canvas. It’s centered in a small southern town, but it’s also momentarily set in a northern town on a small river, in the Pacific on the island of Okinawa, and all over France, most notably in Paris, and then on into Belgium. This is due, I believe, to the increasingly permissive narrative powers you give to Jay Langley, whose father offered so little of himself—revealed so little of himself—that you, the author, allow Jay to take what he needs and create what he doesn’t know. Is that fair?

All right. Here’s a question, maybe the key question as far as I’m concerned. Father Figure is not a long book as novels go, but it’s painted on a broad canvas. It’s centered in a small southern town, but it’s also momentarily set in a northern town on a small river, in the Pacific on the island of Okinawa, and all over France, most notably in Paris, and then on into Belgium. This is due, I believe, to the increasingly permissive narrative powers you give to Jay Langley, whose father offered so little of himself—revealed so little of himself—that you, the author, allow Jay to take what he needs and create what he doesn’t know. Is that fair?

He must have the story, the backstory, for the only story he keeps hearing from people around town, and especially from his uncle-aged cousin, who did fight in the battle of Okinawa, was what fabulous figures his father and mother were. They bore no resemblance to the post-war father and mother he came to know.

You allow Jay Langley to narrate the moment of his own conception.

Well, he’s got to be sure, doesn’t he? He has become the narrator, and there are—there might be—competing claims to his fathering.

And for the son to follow the father through the Battle of the Bulge so that he’ll know what did and didn’t happen on that snowy cow pasture in the Belgian Ardennes. What’s the price of all these narrative and psychological liberties?

I’ve always felt, and I’d bet the house that you have too, Paul, that a novel that does not test the limits of sanity not only does not break new ground but can be accused of playing it safe on terms that the novel itself has established. That does not mean that by the end of every book someone has to run Lear-like spouting mad poetry into the storm. But it does mean testing the limits and in so doing extending them if only a bit. One thing I did tell my writing students, and am happy I did, was to read carefully Stanislavski’s book An Actor Prepares to get a sense of what it means—in the degree of detailing, in the degree of immersion—to inhabit another character. Whether you’re writing that character into being or whether, on the stage, you’re giving him flesh and blood of your own, you’re going to test the limits and extend them, or else the book will lie like a nicely crafted and very vivid-seeming corpse on the page. And what about, you say, a comedy of manners? Does every novel have to be a pyscho-drama of some sort? And I’d answer if a whole body of character-determining manners isn’t a crazed concept in itself, I don’t know what is.

Has there ever been a successful Southern comedy of manners?

Has there ever been a successful Southern comedy of manners?

Maybe that is what Flannery O’Connor was writing. She’s been accused of writing practically everything else.

What was it that Carson McCullers, another Georgian, I believe, and a self-exiled Southern writer, said about the South?

A number of things, I guess. What did you have in mind?

“I go back South every time I want to renew my sense of horror.”

That would be one of them. But I hope we’re past that and those days are done.

Even if that means some future great literature won’t get written?

Now, I didn’t say that, did I? From one novelist to another, please don’t put words into my mouth.