I met Julie around ten years ago when we were in residence at the Ragdale Foundation. We were both staying in the historic, beautiful but drafty, main house during a snowy stretch. Julie had a private bath, but I had a room with good heat. Over cups of tea in the kitchen we discovered we liked the same tea, black, strong, with milk, and were reading the same authors, Alice Munro, Michael Cunningham, Andrea Barrett. In the years since Julie and I have kept up.

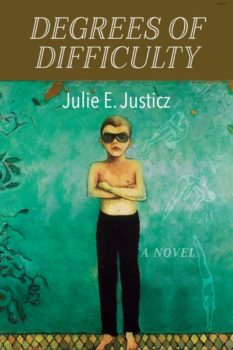

Now with the release of her novel Degrees of Difficulty from Fomite Press, also my press, I’m delighted to learn more about her novel and her writing process.

Interview:

Lynn Sloan: Degrees of Difficulty is a novel about a family that struggles with the overwhelming needs of the youngest son, Ben, born with profound disabilities. The book opens when Ben is about fourteen years old and it spans about twenty years. You write from the points of view of the parents, Perry and Caroline, and Hugo and Ivy, Ben’s older siblings, and each of these four individual stories is full of ambition, desire, secrets, conflict, and buffeted by pressures outside the family. A less ambitious writer would have settled for telling one person’s story. Why did you decide on such a complicated—and I’ll say, satisfying and rich—undertaking?

Julie Justicz: Writing from multiple points of view was not my original intention. I started the novel in the first-person perspective of Ivy, the only daughter and oldest child in the family. She came off as smart, put-upon, a little brash and dismissive. Perhaps what you’d expect from the oldest child of this complicated family. But in revising the early drafts, I realized that I wanted to accommodate the different experiences of different family members. Ivy alone couldn’t do justice to the story. I wondered about her parents, her brothers . . . how would their experiences differ from Ivy’s?

Perry, the father, came quickly; I understood his “game face on and best foot forward” attitude. Caroline, the mother, and Hugo, the middle child, were harder for me to capture, to make human. I needed to find a way to show the mother’s growing depression, thwarted career desires, suppressed anger, and also make her sympathetic. And Hugo, the middle child—a little too perfect to be true? How then to make him real? Where were the chinks in his armor?

I also experimented with a voice for Benjamin, the youngest child, born with profound disabilities. I wrote him with a lyricism that didn’t jibe with his lived experience. So, I decided on four points of view, showing each family member’s connection with Ben . . . how the experience of loving him and living with him shaped everyone, impacted choices they made and changed the paths they followed.

Your brother Robert was born with the same chromosomal irregularities as Ben, and other significant elements in your novel are similar to your own life. Why fiction instead of memoir?

Your brother Robert was born with the same chromosomal irregularities as Ben, and other significant elements in your novel are similar to your own life. Why fiction instead of memoir?

All my writing has roots in my childhood; my stories usually begin with images, sounds, flashes of memory that I grab on to and observe from different angles. But these autobiographical shards do not make a story; rather, I find new voices, build setting, shape characters, create dialogue, and fashion all the other elements to make a new literary world that allows exploration of an emotional truth that has somehow commanded me to write.

Can you recall the moment when you decided to write this book? What was your initial inspiration?

Two inspirations that I recall are: (1) a swimming pool, and (2) an article I read in the New York Times Sunday Magazine about siblings of kids with disability.

My brother Robert loved water; he’d spend many hours paddling around in our backyard pool which Dad kept heated at almost bath temperature from April through September. Water seemed to soften his sharp angles, minimize his physical limitations; he relaxed and giggled a lot in the pool. When I think of Robert, it’s usually a memory connected to water. The novel began with a short story, a sister watching her two brothers in the backyard pool.

The second inspiration was an article about how some siblings of kids with disabilities drink up the responsibility of caregiving, make a life of it, while other siblings eschew it. Stay or go? Anger or compassion? Or something more complicated . . . more human? Turns out that that’s what I wanted to explore.

The family is a gravitational center that holds all your characters close, but for the females, Caroline, the mother, and Ivy, the daughter, their individual needs and desires acts as antigravitational forces. When did this emerge?

I love this notion of antigravitational forces. Thanks for noticing this, for naming it. I think that this theme emerged when I became a mother for the second time. Having two young children in the house when I wanted to disappear and write made my family, as you say, an antigravitational force.

Caroline and Ivy feel the burden of caregiver expectations increasing and conflicting with their personal aspirations and professional growth. Caroline’s career suffers and she resents this and feels guilty for being resentful and grows increasingly depressed. Isn’t depression sometimes thought of as anger suppressed? Ivy is angry as the novel starts . . . how will she navigate her education, her career, while still feeling a complicated love for the brothers she leaves behind?

Work is important to each character. Perry is in construction. Caroline is a scholar of Shakespeare and a professor. Hugo, I’ll say competitive diving is his work. Ivy becomes a doctor. It’s unusual in a novel about family and relationships for the working life to be rendered with such authenticity and given such weight. Was this something you set out to do?

I don’t know that I set out to do this, but once I established their careers, I did want to learn about the exact type of work they did, figure out what attracted them to it, and how that attraction might show something about their nature. That meant research on reproductive endocrinology to learn about Ivy’s work. I read up on spring-board diving for Hugo, analyzed late Shakespearean plays for Caroline, and explored new home construction for Perry. That part of writing fiction is fun for me . . . it allows for digression and exploration and yes, procrastination. The hard part is to get off Google and cull from all the different source material the right amount of technical language, all the tools and trade secrets, the work environment associated with a given profession to shape your characters, to bring them to life.

Did you find it hard to write within the point of view of any of your characters?

Yes. I had the hardest time writing in Caroline, the mother’s, point of view. The challenge, I think, was to reveal her anger and her sadness about the sacrifices she’s had to make, without taking away or diminishing her deep and enduring love for her husband and her children, especially for Benjamin. It’s a truism that parents of kids with disabilities often divorce as a result of pressures—financial, emotional—and conflicting desires, beliefs about how best to care for their child. And, women are presumed to be the ones who stay, the ones who will sacrifice anything for their child. Like many people, I’ve had to push against my own assumptions about how a family, and, in particular, how a mother would or should navigate these situations. I had to grow as a writer to explore Caroline’s emotional complexity, to make her both flawed and sympathetic.

You render the difficulties of living with a severely disabled child with understanding and precision, from the daily—dressing, bathing, feeding—to the medical emergencies, to the unending search to better the situation, and the inevitable setbacks. Yet this book isn’t grim. It’s absorbing, full of adventure, and genuine warmth. How did you find this balance?

I think the book isn’t grim because Ben is a loving, mischievous person first, and a person with disabilities second. If you get to know the human being, the quintessence of Ben, then caring for him, while frustrating and exhausting and overwhelming at times, cannot block out the joy that comes from loving him. That isn’t meant to sound Pollyanna—obviously some tasks like changing diapers on a 14-year-old boy are not pleasant, and managing a grand mal seizure can be terrifying—but on the other side of these tasks and traumas, there is always the boy, the teenager, the young adult who smiles impishly at you, asks you in his macro sign language to play hide and seek, or to turn on his favorite Where’s Spot video for the thousandth time.

You’re a lawyer. Your career is devoted to social justice. When we first met, before I read your work, I wondered if your writing would be stained with legalese or come off as didactic. Instead your language is gripping, graceful, full of sharp insights and vivid details, and a pleasure to read. How has your training as a lawyer effected your writing?

I’m not a good legal writer (I hate the passive voice that seems to pervade lawyerly analyses), and truth be told, I’m probably not a good lawyer. I think I lack a certain . . . logic. I spent three years of law school trying to make stories from the dry case law. Where was the plaintiff going with that sack of fireworks? Was he hurrying to catch the train because he was in love? My torts professor was not interested in exploring these questions, but that’s where my head was. I was like a foreign exchange student who understood only about a quarter of what was said in any class. I probably should have dropped out; but I got my law degree, and, glory-be, I found a thousand different ways to work with civil rights and legal services organizations, from grant-writing to communications to project development. And over the past thirty years, the passive voice has seldom been used by me.

You’re a runner. Do you find a connection between running and writing?

Oh definitely. Getting outside for a few miles doesn’t clear my head so much as get my thoughts spinning. On a run, I work through plot complications or structural problems in whatever I am writing. My brain composts thoughts and memories. Often, I will have what seems like a brilliant insight mid-run, only to find that it’s nonsense when I get back to writing. But no matter the outcome, a run gets things churning. I come back to my desk renewed, ready to try again. The other connection I should note is that writing a novel is like training for a race; you have to show up and put in the time, day after day, if you want to get the damn thing done.

What kinds of research did this novel require?

There’s required research and there’s all the “research” that I conducted when I was avoiding writing. The required research included learning about reproductive endocrinology, genetics, some construction terminology, and the elements of springboard diving. I got waylaid by the four humours (the ancient idea that personalities are influenced by deficiencies or excesses four bodily “humours”—blood, yellow bile, phlegm, and black bile), and read a lot of Hippocrates, Galen, and their heirs; initially I thought the humours would provide my novel an over-arching structure—each of my four narrators would have a predominance of a particular humour. I gave up on that idea during the second or third draft, though you might find a trace or two of this philosophy still in the novel.

I know this novel went through many changes and revisions over the years—

Ten years. Not a decade of steady work, but periods of intense focus, followed by months where I had to put the novel aside for other reasons—family needs, work demands. I thought I had finished it once, but several readers, including the editor at Fomite, told me they didn’t like the second half of the novel. So, I toyed with changing it, made a few minor modifications, but it didn’t get better. It took me another three years to accept the input and really tackle the problem. What was I avoiding?

How did you know you had come to THE END?

Once I stopped being defensive and fully accepted the feedback I’d received from several readers, I lopped off the old ending and gave up on a rather-too-coincidental final act that wasn’t working. Slash and burn. That was freeing. When I sat down to write, the new ending came fast and furious. I shared it with my writing group, and my editor, and they agreed with me—that the revision was satisfying in a way that the prior ending had not been. They knew it; I knew it. I’d reached THE END.

What writers have influenced you?

Many of the writers whom I love are completely different from me in terms of style and form. Alice Munro, William Trevor, Marilynne Robinson, Tessa Hadley—a few of the masters that I revere. Those who have influenced me most write with a very close point of view, often a young narrator, and always an emotional intensity. I am thinking about Jesmyn Ward, Edwidge Danticat, Karen Russell, Lorrie Moore, and Elena Ferrante—there’s an immediacy that excites me, that I strive for in my writing.

What are you working on now?

I am revising my second novel, tentatively called Conch Pearl, which is set in the Bahamas and tells the story of a young girl trying to escape a dangerous situation, which is larger, more diffuse than she can understand. I’m at the point where I’ve written most of the narrative, but something major needs to shift for the novel to work. What is it? A structural issue? A plot problem? You know how it is . . . you plug away until you know it’s done.