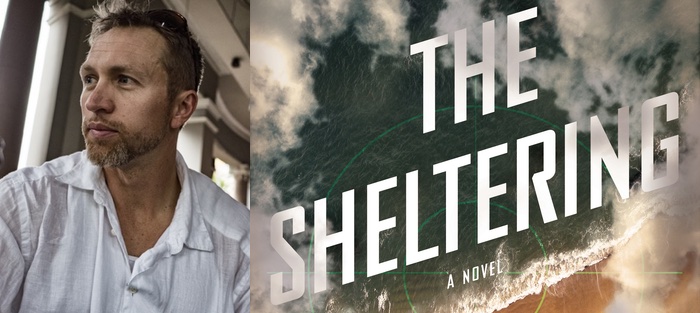

I first met Mark Powell at the Southern Festival of Books in Nashville this past October (2015), but we’d been in email contact for a couple of years before then, as Mark had agreed to contribute a story to an anthology that I was editing. But I knew of Mark even before that. We missed each other at the University of South Carolina – I arrived after he had left – but a friend gave me a heads up about his debut novel, Prodigals. His subsequent novels have established him a new voice in Southern literature, and his latest is a gripping meditation on silence and war, private and public wars, The Sheltering (University of South Carolina Press, Story River Books series). We were going to meet up again in February for the inaugural Deckle Edge, a book festival in Columbia, SC that was founded after the SC Book Festival announced that it was closing its doors last year. Unfortunately, Mark could not make it. Still, I wanted to continue something of our conversation, begun in Nashville, about what we gain as writers from readings and festivals.

Mark was going to be on several panels at Deckle Edge, one of them titled “Rough South.” I had spoken with another of the panelists, Ray McManus, about what he thought “Rough South” meant. He said it is writing that has “at the core of it something rough — violence, drugs, alcoholism — but not for the celebration of ignorance or the trip toward self destruction,” instead to witness the “struggle to get by physically, emotionally, economically, perhaps even spiritually.” With that in mind, I reached out to Mark about his thoughts on festivals and readings, The Sheltering, and what the “Rough South” might mean to any of these.

Interview:

R. Mac Jones: We missed you at Deckle Edge.

Mark Powell: First, let me say how sorry I was to miss the festival, particularly given that it was the inaugural festival, and given that so many good friends and great writers were on the panel (David Joy, George Singleton, Ray McManus). I always feel a wonderful sense of contentment coming back to Columbia. It was in Columbia, straight out of undergrad, and working at a used bookstore off Two Notch Road, that I first started to write. So returning to Columbia always feels like returning to that sense of promise. I knew absolutely nothing then, but I felt like the world was in front of me. That’s a hell of a feeling to have.

As far as writing goes, what is that feeling replaced with now? The joy of publishing can turn into feelings of responsibility when one sits down to write. For others, I know, each new project is a fresh start. What about you?

The urgency of not quite getting it right—that seems to be the catalyst of my writing, for both good and bad. You want to get something across and you know you aren’t. But you’re circling, hoping you get closer, tighter. That’s the sense for me. It’s almost a contained panic.

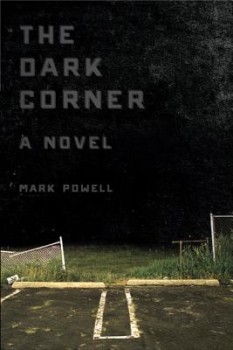

Circling, closing in, those seem to be subjects for you, as well as a way to write. I’m thinking about the beginning of The Sheltering, but also The Dark Corner. In the latter, there are men coming, eventually, inevitably. In The Sheltering, it is the circling drone.

One thing I’ve realized as I’ve gotten older is how little of our life is really under our control. For years, I fancied myself a sort of Camus-toting existentialist. But gradually I’ve come to see that most of life is circling, that forces are at work. I say that, and I realize as it comes out of my mouth that it’s both true and ridiculous. But I think that tension – free will versus fate – is where serious literature comes from. It certainly did for a writer like Dostoevsky. So maybe what I mean is that what I’ve come to understand is that we are actors both constrained and not, and that you have to live in that tension. You have to write in it, too. Which is what I’m trying to do.

One thing I’ve realized as I’ve gotten older is how little of our life is really under our control. For years, I fancied myself a sort of Camus-toting existentialist. But gradually I’ve come to see that most of life is circling, that forces are at work. I say that, and I realize as it comes out of my mouth that it’s both true and ridiculous. But I think that tension – free will versus fate – is where serious literature comes from. It certainly did for a writer like Dostoevsky. So maybe what I mean is that what I’ve come to understand is that we are actors both constrained and not, and that you have to live in that tension. You have to write in it, too. Which is what I’m trying to do.

There is also, in both novels, an accounting of the mundane things of life in preparation for the momentous event.

Wasn’t it O’Connor who said the makings of fiction are as plain as dirt? For a long time I thought whatever grace comes to us in this life comes in abeyance. I sense now that whatever graces comes arrives in the everyday, the mundane events that, as you say, prepare us for the momentous. (And yes, I realize I’m sounding very middle-aged here.)

The mundane is often weighing commitments, though. In The Sheltering, one character (Donny) asks his brother (Bobby), several times if he is “all the way out,” referring to Bobby’s military status. That concept seems to play a larger role in the novel – the danger and necessity of being all in or all out – and, possibly, much of your writing and the act of writing, too.

All the way in or out has such appeal, doesn’t it? To operate at one extreme or the other. But it’s dangerous, I think, in both the literal and figurative senses. Bobby doesn’t understand that. Bobby is one of those jagged edges that catch light so beautifully, and then, before you even realize it, cut you.

The edges don’t always let us know they are there – jagged edges, cliff edges. They look like so much else in the landscape. There is the silence that threatens. I’m thinking again about the drone in The Sheltering.

We seem to be constantly reconfiguring the angel of death. Missiles, drones…cells that won’t stop dividing. That insidious silence, right? That it’s silent, and that we know all the same that it’s waiting for us – that’s not something humanity is likely to ever think around. And that’s probably a good thing.

Then some of those things blow up. Then there are the pieces left. You have mentioned Denis Johnson as an influence before. I certainly see a similar knitting together of pieces in your writing. Any thoughts on his influence?

Johnson is one of a few writers – Robert Stone, Joan Didion, Ron Rash, Cormac McCarthy, Don DeLillo, Annie Proulx would be others – that I’ve spent my reading life immersed in. The thing about Johnson’s books is that none are perfect books in the traditional sense of a unified structure, but they are actually better for it. They are every one magnificent failures. They want what you can’t get – they want the holy, they want to touch the hem of the garment – and you can’t have that, it can’t be done. But no one seems to have informed Denis Johnson of such. He seems to write in a state of glorious junkyard delusion. That’s the place I aspire to.

You mentioned place, obviously in a different sense, but I wanted to ask about one of the panels you were scheduled to be on at Deckle Edge, one about place, the “Rough South.” How do you think that phrase applies to your writing?

You mentioned place, obviously in a different sense, but I wanted to ask about one of the panels you were scheduled to be on at Deckle Edge, one about place, the “Rough South.” How do you think that phrase applies to your writing?

People think the South is homogeneous and in so many ways it is. In so many ways the South is now a form of theater where we play at being Southern, like in the pages of something like Garden & Gun. But there is a South that remains on the edges, there is a rough South. My sense is that the job of a writer is to direct his or her gaze at what we would otherwise hurry past. For me, that is what’s called the rough South.

Why gaze there? For it to be recorded, as something rough? Or redeemed in some way in being written about?

I think it has something to do with authenticity. Whether it is rough or poor or what we’ve been taught to be embarrassed by – what is more embarrassing in modern America than, say, someone who actually believes in something? – at bottom it is about something being real, and the real always frightens. We talk about “authenticity” as this desired thing. But few people actually want it.

What panels have you done in the past that made you rethink your novels or approach them in a new way, either because of the panel’s theme or connections or comparisons to the work of other writers on the panel?

Panels are always useful. You get to hear writers attempt to articulate what they are doing. Sometimes I’m not sure what exactly I’ve done, or meant to do, until I talk about it. The first panel I was ever on was at the Southern Book Festival in Nashville in 2002. I was on a panel about coming of age in the South novels and it wasn’t until I stepped onto the lectern that I realized, yeah, that’s exactly what I wrote.

In 2002, it would have been Prodigals. That’s really interesting to hear. What was it to you before then, if not a coming of age novel?

In 2002, it would have been Prodigals. That’s really interesting to hear. What was it to you before then, if not a coming of age novel?

It was just something I felt compelled to write. It started as a family story my grandmother told me, but pretty soon I realized I was inventing things. So it was a novel, yes, but to what end? Why was I writing a novel? I didn’t know then, and still don’t. Except that I was compelled, or called, or however you want to say it.

Knowing how to write it is one thing, and how to read it is another. How do you choose a passage for a reading? Is it solely a time thing, or do you recognize certain “beats” or scenes that lend themselves to readings?

It’s a timing thing, but timing in the sense of rhythm. You want something contained, but also something that has an individual heartbeat. It has to convey the heat of the book and it has to do it in a fairly quick manner. When I find a good section to read I tend to latch onto it.

At the Deckle Edge readings, as at other festival reading, folks wanted to ask writers about craft, about getting started writing. Any advice you would have shared?

Find the writers that make you want to put down the book you’re reading and start writing. And then read everything by and about that writer, the books, the bios, the journalism, the criticism. Find the voices that speak to you and then know them inside and out. You’ll mimic them at first. But eventually, hopefully, your own voice will emerge.