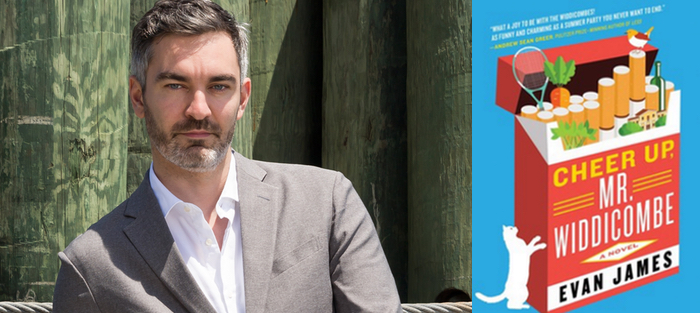

In their newly repurchased and redecorated Bainbridge Island mansion, the heroes of Cheer Up, Mr. Widdicombe, Evan James’s debut novel, are refurbishing themselves. Mr. Frank Widdicombe, restless and cranky since the cancellation of his annual trip to France, has started writing a half-grumpy half-larking life manual, The Widdicombe Way. His wife, Carol, suffering her husband’s gloom secondhand, has hired a gardener named Marvelous Matthews to help her prepare their home for a midsummer garden party that she hopes will get her featured in a glossy interiors magazine. Marvelous pines cluelessly for Gracie Sloane, the Widdicombes’ celebrity guest, whose bestselling New Age self-help workbooks turned Marvelous’s life around. Gracie meanwhile pines for Frank, who pines in turn for the affections of a stray cat that prefers Marvelous ever since the gardener gave it a piece of raw shrimp.

Such are the dramas that spin the whirling plot of Cheer Up, Mr. Widdicombe (Atria Books), a contemporary Bainbridge refurbishing of the classic mansion comedy. Part of James’s brilliance is his ability to make his characters both deeply absurd and fully human. Christopher, the disaffected-from-everything Widdicombe son, on summer break from RISD, attempts in secret to exaggerate his “son-ness” into performance art, only to find himself full of unironic filial love. Another Widdicombe guest, Bradford, avoids his screenplay, about an abstract and terrifying atmospheric menace that settles over Puget Sound, only to find himself abstractly terrorized. It’s a novel full of moods but much fuller, in the end, of heart.

Evan James is very tall, very kind, preposterously gorgeous, as hilarious in real time as he is on the page. We began this interview after I heard him read from Cheer Up, Mr. Widdicombe at KGB Bar in Manhattan. Reading, he weighted his sentences with impish emphases and waited for us to finish laughing so he could go on to the next line.

Interview:

Mark Mayer: I love your epigraph, from Theodore Roethke: “We think by feeling. What is there to know?” I’m curious how you think (or feel) it relates to the work of writing a novel—and this novel in particular.

Evan James: I’ve been fascinated by Theodore Roethke since I was a teenager and first read poems like “Root Cellar” and “The Waking.” He was a kind of presiding artistic spirit on the island—he taught at the University of Washington, and he actually died on Bainbridge Island in the 60s while visiting friends. He had a heart attack in their swimming pool. The site of his death is now a part of the Bloedel Reserve, a forest and botanical garden. The pool was filled and eventually became a sand and rock garden designed by Koichi Kawana. There’s no indication that Roethke died there, but I usually make a visit when I’m on Bainbridge.

To answer your question, though, that line from “The Waking” came to me after I had finished one of the earlier polished drafts of the book. For one thing, it felt right as an amusing summary of what my characters do in the novel: muddle through toward a comic destiny, guided by intuition and nature and feeling. I’d say that writing the novel—which I started ten years ago—felt pretty similar. I’m more of a “sit down at the desk and see what happens” kind of writer, and I’m always seeking novelty, newness, a feeling of being present and alive while I work.

Cheer Up, Mr. Widdicombe is a very—and constantly—funny novel. There’s a laugh line in every paragraph. But it’s not a joke book. I found myself really caring for even the absurdest of your characters, even in their absurdest moments. How do you think about the relationship between absurdity and meaning in your work? What work does comedy do in carrying a novel forward?

For me it all begins with amusing myself. I believe you have to learn to amuse yourself first in order to amuse anybody else. It’s like certain other pleasures in that way. That provides intrinsic interest while I work, which helps to carry the writing forward.

You’re right, though—if it were just that, I’d get bored and tired of myself and would end up with characters who were only there to serve the comedy. Too much emphasis on joke-making or comic routine and you end up with shtick. I want to make discoveries. Which was why, after a few drafts, I started to explore the inner lives of the characters in much more depth than I had before. That opened up new ways forward for me and helped me see why some scenes weren’t working—they were there because I got caught up in the routine of absurdity. I started spending a lot more time thinking and feeling through what really mattered to my characters.

You’re right, though—if it were just that, I’d get bored and tired of myself and would end up with characters who were only there to serve the comedy. Too much emphasis on joke-making or comic routine and you end up with shtick. I want to make discoveries. Which was why, after a few drafts, I started to explore the inner lives of the characters in much more depth than I had before. That opened up new ways forward for me and helped me see why some scenes weren’t working—they were there because I got caught up in the routine of absurdity. I started spending a lot more time thinking and feeling through what really mattered to my characters.

This has a lot to do with how I experience the world. Life often feels overwhelmingly absurd and viscerally meaningful at the same time. I wanted to write from that feeling. So, even though my book is a satire of sorts, it’s also a work of loving fascination. I have a lot of affection for my characters. I care about their inner lives. I’m curious about them and I care about what happens to them. All of that made it much more interesting for me to sit down at my desk.

The novel’s narration braids together seven point-of-view characters, all of them Widdicombes or guests at Willowbrook, the family’s new Bainbridge Island home. There’s something dashingly British about it—am I wrong?—roving among the motley minds of the manse. There’s even an occasional direct address to us readers. What other manses or novels were your models as you invented Willowbrook?

Yes, that’s exactly the case. I started writing it while under the spell of P.G. Wodehouse. His Blandings novels excited me because they often had ensemble casts and were organized around a central locale. Wodehouse uses a third-person, omniscient narrator in these books—one that is, of course, highly amused and witty. Evelyn Waugh’s work also matters a lot to me, Brideshead Revisited and A Handful of Dust in particular. There’s a scene at the end of my novel where Frank and Carol Widdicombe start talking to each other in British accents—a moment of homage.

Around the time I started, something else happened: a historic home on Bainbridge Island was put up for sale, the Westinghouse-Lindbergh House. So I was looking at this real estate listing—it’s beautiful. I drew some inspiration from it. Sometime in the late 20s or early 30s, a descendent of the electricity titan George Westinghouse bought the house. He was from the East Coast and seeking a safe place to raise children. At that time, some wealthy people feared for their children because of a series of high-profile child kidnappings, like the kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh’s baby. Oddly enough, Charles Lindbergh’s son Jon purchased the home in the mid-60s.

How did you conjure these characters, each totally believable and totally bizzare? Early in the novel, Michelle, perhaps the sanest among them, worries that their “all-around eccentricity” will rub off on her. How do you find the center of an off-center character? How do you balance off-balance characters against one another?

The first thing that came to me was Frank’s voice. I was visiting family on Bainbridge Island. They’d started attending a church, though they hadn’t been churchgoers before. I went with them. During the service a very young girl came out and sang “Amazing Grace” in full-on imitation American Idol style. Melisma to the max. I was already feeling irritable, as one sometimes does when visiting family. The situation felt absurd to me. This irascible voice came into my head that I wrote out later. Frank was on the scene, describing a girl singing the old novelty song “Mairzy Doats.”

So, yeah, totally believable and totally bizarre. As Gogol says in one of my favorite short stories, “The Nose”: “Perfect nonsense goes on in the world.”

This brings us back to the balance between absurdity and a meaningful inner life or psychology. Some of my characters did threaten to tip too off-center in earlier drafts, because their desires and how they went about pursuing them were too slapstick.

You have to connect with real desire and real pain—the universal in the specific. I exaggerate Gracie’s self-help writing for comic effect and at the same time believe in what she’s doing. It grows out of her real struggle to live a mindful and authentic life. I bring her and Marvelous together in a light, almost frivolous way, but at the same time their love story contains serious conflict and ambivalence and fear—the fear of starting something new, of hurting someone else, of reckoning with entrenched patterns. That was all written from a place of emotional truth.

The novel is fascinated with the world, or worlds, of self-help. Your characters attend New Age conferences, converse with AA sponsors, celebrate “serenity days” and “the week of strength,” consider Buddhist adages, and attempt to write their own larking—or maybe serious—self-help manuals. You even include a passage from a fictional spiritual workbook. What’s your relationship to self-help literature?

I have a great relationship with self-help literature. I just wrote an essay, “In Praise of the ‘How To’ Creativity Workbook,” about my love of creative self-help and practical self-help workbooks.

I read self-help all the time. I’ve worked through The Artist’s Way twice, and Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit, Henriette Klauser’s Writing on Both Sides of the Brain. Right now I’m reading Brené Brown, whose work can be found in the self-help section. Is it “self-help”? She’s a research professor at the Graduate College of Social Work at the University of Houston.

Self-help gets a bad rap because some people do shoddy work trying to cash in on trends. So what? The same could be said for fiction, theater, movies, art. Trust yourself to grapple with whether something could be inspiring or helpful to you or whether you’re being hustled. (Or both!) There are some extremely intelligent, wise, creative people writing self-help. I never understood why people would close themselves off to that just because there’s also plenty of get-rich-quick snake oil. It’s a complex world.

The constant invention of new systems, concepts, and vocabulary in self-help excites the comedian and the craftsman in me. It’s a word-lover’s wonderland, which was why I had so much fun with Frank and Gracie’s dueling self-help books. Lately I’ve actually been flirting with writing one myself.

How did you build this plot, with its seven major character arcs all complicating during the Widdicombes’ midsummer fete and then culminating around Green Dawn, a New Age festival? It seems like you had great fun playing architect. How did you approach it?

Great question. It’s one of those things that I learned by doing, just feeling my way through for timing, for a balance of scene and summary, etc. At various points I tried to make an outline, since I figured I had some ready-made genre conventions to work with, but it never turned out well. Things would mutate wildly while I worked. New ideas and intuitions about sculpting plot emerge in the process. My outlines always ended up in the trash.

One thing that helped when I began, though, was that I had absorbed a certain pattern from other comedies: that every now and then you had these big clearinghouse scenes—a party, a big event, a wedding, whatever it is—where you bring all the characters together and dramatic things happen. In between those, you have scenes and summary where you’re working with individual characters or exchanges between a few people at most. It’s this movement between private life and social life. So, I established the bigger clearinghouse scenes earlier on, and that was a big help in organizing the plot.

I find thinking about form and structure really stimulating. Intrinsically interesting. I love that you use the word “architect,” because it speaks to a deep, foundational creative desire of mine. Architect was my dream profession when I was a kid. I used to beg my mom to buy me those transparent green stencils from the hardware store that you use to draw aerial views in architectural or landscaping plans. I often think about the built environment when I walk around the city or sit in a coffee shop or wherever. Moving back and forth between contemplating the parts and the whole, I think that’s key to any creative endeavor.

The figurative language your characters use in their inner monologues is so perfect. It reveals their own goofy frames of mind but also gets the object in question exactly right. I’m thinking, for instance, of Carol Widdicombe describing the dark flecks on the screen of her iPhone as “flies trapped in honey” and then describing the fissure around the edge of the phone into which she pushes the dust as “the crack in the earth that led to hell.” Tell me about the joy and science of the simile. And who, for you, are the heroes of figurative prose?

I love figurative language. It does bring me a lot of joy, because it’s part of a process of invention and of discovery—of discovering the way that your characters or your narrator see the world. In an interview with Clive James, Martin Amis says something to the effect that style is an expression of perception, not something poured on afterwards. So, I think there’s a lot of pleasure to be had in learning what kinds of similes or metaphors a character would use.

I love figurative language. It does bring me a lot of joy, because it’s part of a process of invention and of discovery—of discovering the way that your characters or your narrator see the world. In an interview with Clive James, Martin Amis says something to the effect that style is an expression of perception, not something poured on afterwards. So, I think there’s a lot of pleasure to be had in learning what kinds of similes or metaphors a character would use.

Some third-person omniscient narrators are more flamboyant in their use of figurative language than others. Wodehouse was a great inspiration for me in that way, because the narrator of the Blandings novels uses similes and such in a distinct and delightful way. “She was a tall, fair girl with soft blue eyes and a face like the Soul’s Awakening.” “He continued to bear the glass aloft like some brave banner beneath which he had often fought and won.” Those are from Summer Lightning. They set a tone for the whole book. You feel the narrator is amusing himself, which gives you something to look forward to.

Except for Bradford, the character who writes horror not self-help, all the main characters are indeed cheered up by the novel’s end. Talk to me about happy endings. Was it hard to find happy endings for these depressive, angsty, recovering characters?

The harder thing was to make the ending feel like a natural outgrowth of everything that came before rather than something tacked on. I rewrote the ending a lot along the way. I threw out one that ended with Bradford alone in his car. It had a much more ominous tone. Only during one of my last major rewrites did I make some significant changes to a couple of character arcs that then led into an ending that felt more right.

I felt from the beginning, though, that things would resolve in a more or less cheerful way, with an atmosphere in which happiness is mingled with other complicating emotions. During one of my drafts it began to become clear to me that this was a story, in some significant sense, about friendships. C.S. Lewis said that friendship accounts for perhaps half of all the happiness in the world, and I believe him.

But no, I never found it hard to write a happy ending. When it comes to happy endings, it was never the happiness that struck me as artificial, but the ending. Plenty of people experience happiness, even if it is a temporary, fleeting state. What they don’t really experience is things ending, because time flows on. I frequently think about what’s been going on with my characters since I left them on the final page. Happiness is not the end.