My favorite conversations about writing aren’t about writing at all. They’re usually about the parts of life we think get in the way of our writing life. How to get the words on the page is a familiar conversation among writers and it is an entirely earnest one. We worry we don’t have enough money, time, or resources, as if that is the only barrier to writing well. Readers tell me again that they’d love to write if only they had the luxury in their schedule. I suspect becoming a successful writer and published author is more about commitment than talent or time. The Affairs of the Falcóns, by Melissa Rivero, is a book that was born out of exactly this struggle. It is apt that Ana, the novel’s protagonist, dreams of owning her own restaurant so she can share her Peruvian recipes with her adopted city, but she’s busy scraping together an existence and stuck in a factory job. As an undocumented immigrant, Ana and her family’s days are about survival with little money, time, or resources leftover for what she really wants to do. Ana’s desperation quiets her dreams. She becomes indebted to a loan shark and reliant on her husband, Lucho’s, cousin for their living. Ana must sacrifice her own wants for the wants of others for the sake of her family’s chance to make a new life even while haunted by a past they can’t escape. Maybe making art in war and dreams during trauma are impossible, and yet we need art most during hard times. We need stories that inspire but also that show us how to endure the devastating realities we are powerless to change. The Affairs of the Falcóns is a timely tale of the American immigrant reality and a sympathetic portrait of the strength and cunning of mothers.

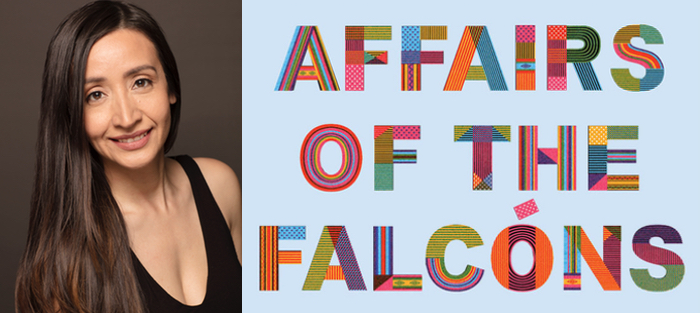

Melissa Rivero was born in Lima, Peru, and raised in Brooklyn. Her writing has taken her to the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, the VONA/Voices Workshops, and the Norman Mailer Writers Colony. In 2015, Melissa was an Emerging Writers Fellow at the Center for Fiction. She is a graduate of NYU and Brooklyn Law School, and currently works as in-house legal counsel at a startup.

Years ago, Melissa and I met in Luis Alberto Urrea‘s workshop at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference. We were both writing novels about home and how to bring a piece of it with you while you make your life elsewhere. Our stories of family struggles had much in common. We kept in touch afterwards and met up again in New York City while I was on book tour for my first novel. Melissa’s debut was due in a few months, and she asked about the mysterious process of launching and how it feels to be on the other side of the book hustle. We talked recently about the stories we keep trying to tell and how to hold space for our writing lives.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: I don’t know about you, Melissa, but it was love at first prose for me. I devoured your scenes during workshop, and I remembered early drafts of them while reading the The Affairs of the Falcóns. It was an honor to know Ana’s story for so long. But our first conversation was actually about the writing life, specifically juggling family, jobs, and books. What have you learned from your debut about the balancing act that you didn’t know when we first met?

Melissa Rivero: That workshop with Luis impacted me in more ways than I expected. I was already a mother, and I couldn’t fathom being apart from my year-and-a-half-old son for ten days. I was also pregnant with my second child. So my husband and son came with me to Bread Loaf.

I remember meeting your family in the dining room one night.

Yes, we often dined there. I didn’t stay on campus–we rented a house down the road, and they hung out with me when I wasn’t in workshop or prepping for it. When I had my one-on-one with Luis, he said something that really stayed with me. He said he was afraid I wouldn’t finish my novel. It was the first time I’d heard my own fear. I could never admit to myself that—with family and working full time—I might not be able to finish. I just didn’t want to acknowledge it, and when he said it, I realized that unless I made the choice to make it a priority in my life instead of simply something that I did whenever I could find the time, I wouldn’t finish. In other words, I had to make time for it, not find time for it, and that was a huge lesson.

That fear seems ever present in Ana too. We are so deeply embedded in her point of view, and yet you’ve managed to create a cast of characters that evoke so much empathy. How do you write in such an open-hearted way toward even those who injure Ana? I’m thinking specifically of Valeria, who has so much power to help and ends up causing the most hurt. Yet I felt sympathy for her pain.

Valeria was second to Ana in terms of how vividly she came to me. I met her in the first few scenes I wrote, but then I decided to write a biography for each of my characters. That’s where I came to realize why Valeria behaved the way she did. I understood some of her pain and her insecurities, and I was sympathetic to that even as I was shocked by some of the things she did. I think one needs to do that as a writer—create characters for whom we have complicated feelings.

It’s complicated with New York City, too, but it’s such a rich literary setting. How does the city represent a useful location for this immigrant story?

It’s complicated with New York City, too, but it’s such a rich literary setting. How does the city represent a useful location for this immigrant story?

New York City is a place for dreamers and for people who are willing to put in the work to make those dreams come true. There are people here from all parts of the world, including Peru.

The geography is such a pivotal plot element.

True. It’s one thing to experience New York as a dreamer from another part of the United States, and a whole other thing to experience it as an immigrant. Especially as a mother with a family.

How is the city different for Ana?

For Ana, New York City was a place where she could find work, where mass transit made accessing and navigating through it relatively easy, and where she could be herself. It’s certainly more challenging to live here for someone like her, but there are opportunities, and there’s community, and this overall sense that, yes, it may be hard, but it’s not impossible to find or reinvent yourself.

The character of Mama, who Ana goes to for loans and favors, has successfully reinvented herself in the city. She holds such enormous power in the lives of women like Ana because she can be both their savior and their punisher. Why was Mama important to the telling of this story?

I needed a character whom Ana could rely on for financial help, especially because she wasn’t going to ask Lucho’s family for it. People who take on the role of lenders, like Mama, are not uncommon in immigrant communities. Mama believes she’s helping Ana, not just by lending her money, but by counseling her. The truth is, it doesn’t matter if she does have any genuine concern for Ana and her situation–Mama is first and foremost a business woman.

These characters of Mama, Ana, and Valeria represent pieces of the desperate immigrant experience. Will you talk a bit about writing each?

I wouldn’t call the experience desperate or even exclusively an immigrant experience, but rather they each represent very different aspects of both the immigrant and female experience. Ana is trying to keep her family together while also holding on to her own dreams. Mama is exploiting the vulnerabilities of others and making money doing so. And Valeria is trying to keep her business afloat despite her personal issues. These aren’t experiences that are unique to the immigrant, but there are layers of complication when you are an immigrant and a woman, and even more so when you are undocumented.

We know the inevitable ending from the beginning, yet it’s still a shock. We’re rooting for Ana in a country and in a life that is absolutely stacked against her. I’m curious: where in the process of drafting did you know the narrative arc and journey Ana had to take?

I’m not a plotter, but, after writing the first three or so scenes, I pretty much knew how the novel would end. I didn’t know what the scene would actually look like or how I would write it, but I had a clear sense of what it would feel like.

Without spoiling it for readers, that final scene is so evocative. The threat to Ana’s family is its own character in the story. I see it as an argument really about the American Dream. Did it evolve while drafting? Or did you always know this direction?

I’m not sure I was conscious of an argument as I wrote. I wanted to tell this one character’s story and I don’t think I had an agenda. Looking back on it now, though, I do think there were many things I wanted to convey by writing it: the complexities of womanhood and motherhood, marriage, family, community, and some of the ugly leftovers of colonialism. Ana was not just one thing—not just an immigrant, or a mother, or a wife, or another worker. I wanted to show her for the full, complex human being that she is, with all her flaws, aspirations, determination, and strength.

Do you see your writing as political?

I didn’t see it as political when I started, but in the midst of it, I realized there was something I wanted to say. Many things, actually. Different readers will want to talk about different aspects of the novel. I hope it changes some points of views or at least gets people talking in a way that is constructive and empathetic. I really just want to get the discourse going.

I didn’t see it as political when I started, but in the midst of it, I realized there was something I wanted to say. Many things, actually. Different readers will want to talk about different aspects of the novel. I hope it changes some points of views or at least gets people talking in a way that is constructive and empathetic. I really just want to get the discourse going.

Is it too soon to ask what you’re working on now?

I’m working on a novel that centers on women at a start-up. That’s all I can say about that for now!

And, really, how are you finding making the time?

I drop off my kid at school in the mornings and have about thirty minutes before I need to head to work, so that’s when I write. I also write on the train ride to work. I write for longer stretches on weekends (usually two to three hours a day). My husband has been very supportive of my work, and without him cheering me on and giving me the space and time I need, I’m not sure I could do it. Actually, I think I could—it would just take me a bit longer.