When I was a new mother, living in Springfield, Missouri, I often took my young son to a nearby park, which had a memorial to a group of women known as the Springfield Three: a mother, a daughter, and a family friend who disappeared in the middle of the night of June 7, 1992. Though so many years had passed, people still left flowers and tributes at the memorial, and I was surprised how immediate the case still seemed to many in the community. On those summer days, I’d park the stroller and sit for a while on the bench dedicated to the women, thinking about their lives and what might have happened to them. In a way that I’m still not able to explain, their story seemed to me to be intimately tied to the landscape of southern Missouri—the long flat roads, the small low-slung cities, and the rolling hills and dark hollows of the Ozark Mountains.

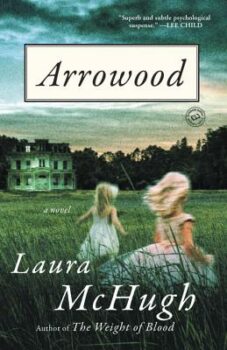

To my knowledge, Laura McHugh has never written a story like this one, and yet I can’t help thinking of her work every time I think of these women. McHugh, who grew up in Iowa and Missouri and still lives in the Midwest, is expert at telling stories that could have come out of no other place. She is the award-winning writer of four novels—The Weight of Blood, Arrowood, The Wolf Wants In, and What’s Done in Darkness—and (in my opinion) comes up with some of the best titles in crime fiction. The skill of her prose and depth of her characterization defies genre, and her work brings needed attention to the people and issues of the place she loves. (She recently started making true crime Tik-Toks about the case of another missing local woman.)

Interview

Polly Stewart: I wanted to start by talking about your life as a full-time writer. How long have you been able to support yourself with your writing?

Laura McHugh: I guess it’s longer than it than it feels like. I was a software developer for my first career, and I lost my job at the end of 2008, right before the birth of my second daughter. That’s when I started writing. But I didn’t get a contract until the end of 2012, with The Weight of Blood.

Laura McHugh: I guess it’s longer than it than it feels like. I was a software developer for my first career, and I lost my job at the end of 2008, right before the birth of my second daughter. That’s when I started writing. But I didn’t get a contract until the end of 2012, with The Weight of Blood.

Can you walk me through what your schedule is like on a writing day?

I have two kids in school—in middle school and high school. I get them both off to school, and then I come home and just treat it like the regular job that it is. I work at night, too, if I can. Sometimes I stay up late when everyone goes to bed, but mostly it’s just like when I had a full-time office job, and that works out really nicely for me.

What about during the pandemic? Were the kids at home with you last year?

Yes, and it seemed like forever! I liked having them around, but it was a little more difficult to get the writing done. I was finishing What’s Done in Darkness right around the time that they stopped going to school in March of 2020. My husband is home a couple of days a week, too, because he works nights part-time, so everyone was here and it was definitely a struggle to focus. I just started doing sprints where I would set a timer for about fifty minutes and tell the kids, “You cannot bother me until this timer goes off, unless it’s an emergency.” So, for fifty minutes, I wouldn’t check email, I wouldn’t look at the internet, I wouldn’t help my kids, I wouldn’t do anything. I would just write until the timer went off and then do a ten-minute break, check my messages, make snacks for the kids, whatever I needed to do, and then get back to it. And that’s how I finished the book with them at home.

Did that affect the structure of What’s Done in Darkness? Did you choose to have short chapters and alternating points of view because they were easier for you to work on in those small windows of time?

I don’t think it necessarily affected the book in that way. The book was pretty much all thought through and mostly written at this point. This book is a little bit shorter than the others, though, so that might be one connection.

We’ve all become connoisseurs of Zoom backgrounds by this point, so I have to ask: is this your work space, here in your kitchen?

Yes, this where I sit. It’s the best for Zooms, because it has the most light. Early on, I had to do an event with some people who had this fabulous lighting, and I was like, “Oh, my gosh, I look like I’m in a cave! I need to work on that a little bit.”

Since I’ve been working at home, I sit at the table and write a lot, or sit on the couch. I sit on the screen porch as much as I can when the weather’s nice. I used to go to coffee shops all the time, and I hope to be able to get back to that sometime.

That’s interesting that you’re so flexible. Some people are very rigid about their writing spaces and routines

Change of scenery helps sometimes to mix it up a little bit for me.

Since it’s such a big theme in What’s Done in Darkness, I wanted to ask you about your experience with Evangelical communities. Did your family attend a church like Sarabeth’s at any point? Or how did you become familiar with that subculture?

I grew up Catholic, but I also grew up in Southern Missouri for the most part, so I had a lot of friends who attended churches like Sarabeth’s. I remember going with a friend to a Halloween event at her church one time. Her church didn’t believe in Halloween—they thought it was evil—and I found it fascinating. I found it scarier and more exciting than regular Halloween. Later on, I ended up having some neighbors that were a part of a church where the girls only wore dresses and had long hair and were homeschooled. I got to know them a bit and I learned a lot of interesting things just from talking to the kids. I was wondering: “What it be like to grow up in that, particularly for a woman, or to come to that later on in your life? What would that be like as a woman?” That was something I kind of wanted to explore.

I grew up Catholic, but I also grew up in Southern Missouri for the most part, so I had a lot of friends who attended churches like Sarabeth’s. I remember going with a friend to a Halloween event at her church one time. Her church didn’t believe in Halloween—they thought it was evil—and I found it fascinating. I found it scarier and more exciting than regular Halloween. Later on, I ended up having some neighbors that were a part of a church where the girls only wore dresses and had long hair and were homeschooled. I got to know them a bit and I learned a lot of interesting things just from talking to the kids. I was wondering: “What it be like to grow up in that, particularly for a woman, or to come to that later on in your life? What would that be like as a woman?” That was something I kind of wanted to explore.

Then, after I’d written What’s Done in Darkness, a neighbor of mine who’s a librarian got an early copy of the book and started texting me, This is my life. I knew she had been in a church like that, but we’d never talked about it really, so that was pretty interesting. She said a lot of people think this stuff happened a long time ago, but it happens now.

There was a line that really struck me about girls who only exist as names in the family Bible. Is that something you came across in your research—this idea of children who really have no existence in the outside world?

I didn’t have a specific example of that from the real world, but I was just thinking that when a lot of these kids are born, if it’s a home birth, it might not registered, and writing it down in the cover of the Bible might be the only proof that this person exists. It was scary to me to think about things that might happen to them if no one is aware that they were ever born. They’re not registered with the school system, they don’t see a pediatrician, so no one outside that community really has the ability to know if they’re okay or if there’s something wrong.

I love all your books, but the one I had to really psych myself up to read was Arrowwood. [The novel is about two young girls who disappear.] Even though I write crime fiction, and I consume a lot of it, bad things happening to kids is sort of a sticking point for me. Do you feel different emotions writing about crimes against children than you do about adults?

Yes, it is difficult. I have children too, and I do think about that when I’m writing stories about children, but then I think about all the stories in the real world about bad things happening to children. There are so many stories in the news where kids have disappeared, no one’s seen them for a very long time, and it turns out they’re being starved to death, they’re locked in a closet. Or their bones are found in their family’s front yard. Writing about it, I would say, is no worse than reading about it. At least trying to write it is trying to make sense of it in some way, or to feel through a mystery and come up with some kind of resolution.

I read an essay where you wrote about your family’s move to the Ozarks when you were growing up, and I was wondering if any of that inspired the story of Sarabeth’s family’s move.

I’m always taking little pieces from my life story. When we moved down to the Ozarks, it was like leaving civilization behind in a way. We were not off the grid, but it was pretty remote. I did draw on that a little bit with Sarabeth’s sense of leaving the world behind and having to start over. As a child, you don’t have any choice in the matter.

I write about Appalachia, which is similar to the Ozarks in a lot of ways. Do you find that readers aren’t very familiar with the place you’re writing about? Do they make assumptions about the place and the people who live there?

Yeah, it’s interesting from all sides of that. With The Weight of Blood, there were people from the area who were angry because they felt that I was showing the area in a negative light. Of course, since all of my stories are crime fiction, that’s how I would write about any place.

Working with an editorial team, I found that they had a lot of questions about details in the book. Copyeditors would point out these little details about the weather and say, “That doesn’t seem right,” and I’d say, “No, really, there might be a tornado and then an ice storm!”

I do feel a lot responsibility in the way I’m portraying this place to people who know nothing about it. I do try to focus also on the strength of family bonds and the importance of family in these small close-knit towns. Sometimes you do see people writing about small, impoverished towns and you can kind of tell that probably they don’t have firsthand experience with that.

I wanted to ask you a little bit about the structure of your books. Several of them have a structure with alternating perspectives in your books. How much planning do you do ahead of time and how closely do you stick to that?

With The Weight of Blood, I had no plot. I had nothing. I was writing by the seat of my pants until I was more than halfway done with the book, which is when I finally realized what was going on and what was going to happen. Then for Arrowwood, I thought I’d outline ahead of time and structure it because now I had a deadline. I had a contract for that book and I thought it would be faster and more efficient and I would waste less time if I had planned ahead. So I made an outline and I was miserable. It did not work well for me. I would just sit at my computer and cry. It really sucked the joy out of it for me.

With The Weight of Blood, I had no plot. I had nothing. I was writing by the seat of my pants until I was more than halfway done with the book, which is when I finally realized what was going on and what was going to happen. Then for Arrowwood, I thought I’d outline ahead of time and structure it because now I had a deadline. I had a contract for that book and I thought it would be faster and more efficient and I would waste less time if I had planned ahead. So I made an outline and I was miserable. It did not work well for me. I would just sit at my computer and cry. It really sucked the joy out of it for me.

I learned through that experience that I’m not going to be a strict plotter, but with each book I’ve done a little more structural thinking upfront. With the book I’m writing now, I’ve already written the end. I know the story, but I don’t know A to B to C to D, which is enough to keep that joy in there for me.

Since you have kind of an ongoing relationship with an editor now, do you send her sections along the way or do you just wait till you finish a whole draft?

Generally, I wait till I finish a whole draft. I have a hard time showing people a partial draft. I used to be in a writing group for a little while, and I loved them, but for me it was always more helpful to have them critique the entire manuscript at once rather than a couple of chapters. The important thing to me is the whole arc, does this work as a whole?

I read in one of your interviews that you are a big fan of true crime podcasts, which is my guilty pleasure as well. Have you heard any good ones lately?

I’ve been listening to Crime Junkie a lot because I had to catch up, I was way behind on that. I just found out about a new podcast called Most Foul and I’m just starting to listen to that one. Now that’s a new one to me and one of my all time favorites. I love In The Dark, too, from the very first season. That has to be one of my favorite ones.

Since you mentioned your next book, is there anything you can share about that project?

Sure. It’s set in a small, dead-end Missouri town that has a meat packing plant kind of at the center, and it deals with a missing person. I love to write missing persons stories. It’s also about family ties and intergenerational abuse and poverty—all those obstacles that are put in your way as a woman in a small town trying to get out.

Have you read anything coming out or recently published that you think is really great?

I interviewed Paula Hawkins recently about her new book, A Slow Fire Burning. I think it’s her best book yet. It’s very character-driven and I love character-driven stories so much. And I’m just now starting Simone St. James’s The Book of Cold Cases, which comes out next year. It’s fun to get to read these in advance and see what other authors are doing. I enjoy that.