In 1925, when Ernest Hemingway published In Our Time, his second collection of short stories, critics struggled with how to categorize their assembly. The stories themselves were individually exalted, but it was how they came together that intrigued readers. It wasn’t just that they were linked by character, but also by geography and theme. Yet they existed as stand-alones and vignettes in a way that chapters in a novel don’t. In commenting on how the characters overlapped, D.H. Lawrence wrote in his review: “In Our Time calls itself a book of stories, but it isn’t that. It is a series of successive sketches from a man’s life and makes a fragmentary novel.” Lawrence was writing about the short story cycle long before it was called that. What Hemingway had done and Lawrence would later do too was write characters that not just reoccur but build in conversation with one another. A story cycle may or may not have a linear progression in their telling, but they have an influence on the overall collection as they construct a world and influence each other’s existence on the page. Characters whisper and shout at their authors. They tap on our shoulders. They inch their way into stories they aren’t supposed to be in. They pop up in plot and surprise even us, those of us with agency in their telling.

In Brandon Tayler’s first short story collection, Filthy Animals (Riverhead), which follows his award-winning novel, Real Life (Riverhead, 2020), the story cycle shines in characters that wrestle with loneliness, desire, and pain. Set in the Midwest, a landscape lush in violent weather and often passive aggressive niceness, Filthy Animals is as raw and satisfying in its pace as it is fresh in its depth. These characters insist on tension, intimacy, and unsentimental truth telling.

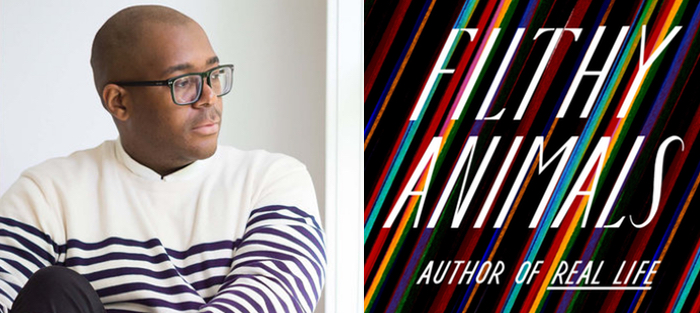

Brandon Taylor is the author of the novel Real Life, which was a New York Times Editors’ Choice and shortlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize, as well as The National Book Critics Circle John Leonard Prize and the 2021 Young Lions Fiction Award. His work has appeared in Guernica, American Short Fiction, Gulf Coast, Buzzfeed Reader, O: The Oprah Magazine, Gay Mag, The New Yorker online, The Literary Review, and elsewhere. He holds graduate degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he was an Iowa Arts Fellow.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: We should probably talk first about the essential Midwestern potluck. It’s an institution and this is where Filthy Animals begins.

Brandon Taylor: Definitely. I like potlucks. Everyone shows up with a competing social agenda. Some people come to show off their casserole and some people come for the free food. They are these nice community building activities. I didn’t know what a potluck was until I moved to the Midwest. Growing up in Alabama, all of our parties were sort of potlucks, but I didn’t know that was what it was called.

What did you call them?

We just called them parties, and you were expected to bring something and if you didn’t, that’s rude. It was part of the social code growing up.

In the opening story of Filthy Animals, Lionel’s loneliness is juxtaposed with a communal gathering and sharing in “Potluck.” In many ways, Lionel is living truthfully, albeit in isolation and recovery, rather than keeping up the front of couples like Charles and Sophie, who have public arguments. When Lionel reflects on this, he says, “And he’d seen them bare their teeth at each other. Was that what it meant to be with someone? Was that what it meant to care?” This seems an even more apt observation as we emerge from social distancing and perhaps watch each other more acutely. I’m thinking also about Lionel’s “reacclimation to people.”

In the opening story of Filthy Animals, Lionel’s loneliness is juxtaposed with a communal gathering and sharing in “Potluck.” In many ways, Lionel is living truthfully, albeit in isolation and recovery, rather than keeping up the front of couples like Charles and Sophie, who have public arguments. When Lionel reflects on this, he says, “And he’d seen them bare their teeth at each other. Was that what it meant to be with someone? Was that what it meant to care?” This seems an even more apt observation as we emerge from social distancing and perhaps watch each other more acutely. I’m thinking also about Lionel’s “reacclimation to people.”

Lionel is struggling to reacclimate for sure. If you are a person who is just recovering from a bout of mental illness and you have just gotten out of the hospital, what a great idea to put oneself at a potluck. A very high stakes social event! At the beginning of the story, he is thinking: Maybe I should not do this. But then the host opens the door, and he’s brought in. Part of Lyon’s decision to attend is because he’s been so isolated, and by himself. There was a real part of him that wanted to re-enter the world in some way. And part of re-entering the world was his ability to connect with other people. He psyches himself up to go to the potluck, but the minute he gets there, he realizes this was a mistake.

A mistake because of his own fragile recovery?

Absolutely. People are actually looking at Lionel and talking to him, and he’s thinking: I have no idea how to do this anymore. It’s a really anxious situation. Poor boy.

Similar to Lionel’s longing, Sylvia in “Little Beast” has a hunger: “There’s a hole in her, and the water’s flowing out, into something else.” Sylvia expresses contempt for the neediness of the children and families she’s charged with protecting. She’s often disgusted by their explicit wants. She moves between families in the same neighborhood cooking, cleaning, and caring with both attention and disregard. I adored “Little Beasts” and the language throughout the collection is so piercing. We linger moments longer in scenes for the impact. I’m thinking particularly of Charles returning to Lionel, as we knew he would: “…at the boundary between the light and the shadow.” Can you talk about the challenge in writing with that precision?

I love that you love “Little Beasts.” That story taught me a lot about technique and craft. That story used to be a part of a different story cycle. When I wrote “Little Beasts,” I was like, “I am going to write a book that has a vowel in the beginning of every sentence.” It was such a pleasure to write.

Later in “Little Beasts” our narrator claims, “There is nothing she can keep inside herself. It’s the kind of life that Sylvia would like to live, but she knows it’s the kind of life that is impossible because the world can’t abide a raw woman.” What might Sylvia mean by “raw woman” and why is it an impossible task?

I’m so glad that stood out to you. I thought it would be cool to look at how an adult woman looks at a younger woman who is on the cusp of that point at which the world tells her how to be. The world has so many ideas on how women should behave. Sophie grew up in such a strict Southern way. I think part of that story comes from my own childhood. When I was a kid, my aunt had a daughter. She was the first daughter born in my family. We had all teenage boys, they would play rough with her, push her into the mud. It was great until she turned six, and all the aunts were like “close your legs” and “don’t sit like that.” Seeing the light in her eyes fade and her realizing that the family treats her differently was so hard. I really wanted to write about that. What is it like to look at a young child and see the things they have coming? Sylvia is mourning that in herself and realizing that once upon a time, she was that free child.

“Flesh” is linked to “Potluck” by the relationship triangle of Lionel, Charles, and Sophie. More is revealed about their growing connections in “Apartment,” “Proctoring,” and in the concluding story, “Meat.” What did you consider when ordering the collection, especially as major characters take turns being minor ones?

It’s a bit of a chaotic choice. I wrote the Lionel, Charles, Sophie stories in 2016. I wrote them back-to-back. I wrote them during a snowy week in Madison, Wisconsin. Part of it was that I had just read the Mavis Gallant collection Varieties of Exile. That book is really interesting because it’s a collection of her stories, but it’s almost like a suite of stories. It was the first time that it had occurred to me that you can write a short story and have it linked to other short stories. You don’t have to leave the world of those characters. I wrote these stories just one after another following my natural entrance. At the end of this I had these linked stories. And when I was putting the book together, I was faced with a choice. Do I let these stories stay and be linked? Or, do I let the book contain stories that reflect those other stories? I decided I want the book to have more than just the Lionel, Charles, Sophie suite. It seemed to make sense to let the linked stories be the central theme. Once I made that choice, everything clicked into place. The structure of the book came out of deciding what was going to be the anchor of this book.

It’s a bit of a chaotic choice. I wrote the Lionel, Charles, Sophie stories in 2016. I wrote them back-to-back. I wrote them during a snowy week in Madison, Wisconsin. Part of it was that I had just read the Mavis Gallant collection Varieties of Exile. That book is really interesting because it’s a collection of her stories, but it’s almost like a suite of stories. It was the first time that it had occurred to me that you can write a short story and have it linked to other short stories. You don’t have to leave the world of those characters. I wrote these stories just one after another following my natural entrance. At the end of this I had these linked stories. And when I was putting the book together, I was faced with a choice. Do I let these stories stay and be linked? Or, do I let the book contain stories that reflect those other stories? I decided I want the book to have more than just the Lionel, Charles, Sophie suite. It seemed to make sense to let the linked stories be the central theme. Once I made that choice, everything clicked into place. The structure of the book came out of deciding what was going to be the anchor of this book.

All the truth bombs, pain, love, and struggle lead to this thesis: “Their light was insufficient to illuminate anything, but for a while, it was beautiful to watch.” The intentionality of the collection radiates. In revision, in clearing the clutter to get to this clarity, when do you know a story is done?

So many of these stories have been drafted and rewritten, so many of them have a new title. When I was putting the book together, I had a version with all the published stories and my editor and my agent were really happy with it. It felt to me like I could publish this book with very few edits and changes. I could be content with the book or I could closely examine the book. I could look at its impulses, its style. I asked myself: “Do these stories represent the best of my work?” Oftentimes the answer is no. Do I send it off into the world but live with the emotional guilt or do I find a way to change into a form of art that reflects me? A way that would satisfy me as an artist.

It sounds like the stories needed room to breathe. The story is changing and so is the world outside.

So true. I think sometimes when I write a story, it represents my abilities at the time. So as I grow, do I want to change my stories to reflect me more now? Even if a story has been published, I don’t see how that version needs to go into the book. I see putting together a collection as an opportunity to amplify and improve different components. Every time I write a story, I’m writing it as part of a manuscript or a cycle. “Little Beasts” is a perfect example, there are so many versions of it, because I am a bit of a perfectionist when it comes to stories. In a story, every imperfection shows and every improvement shows.

In “Flesh” Charles reveals the pain we inflict on our own bodies and how our body endures the suffering because of our behavior. Farnland, the dance teacher, desires his students, abuses them, throws fits, and yet “…Charles had done nothing to stop him.” There is a duplicity and a complicity around the body and consent. What does dance feed in Charles when it costs him so much?

I love dance. I think about it all the time. It’s an art form where the art lives in your body. Charles wants to be able to live the rest of his life on his own terms. He doesn’t want to just teach choreography, he wants to decide what he wants to do. Yet through all that, he does have this injury. And it grows increasingly severe. That story is about the different bargains we make to pursue our artistic life. That moment where Charles almost breaks his foot, he was lucky and that moment changed him. How close you are to losing it all. Sometimes you aren’t aware of how badly you want something until your access to it is dwindling.

Similarly, Sophie, who is a more talented dancer, speaks of the intersection of body pain and control in her purging. In the dance that is Lionel, Charles, and Sophie, they are all seeking that ping and clarity, but is their connection actually about control and power?

When I first wrote Sophie, I really didn’t know how to write women. Later on, when I learned how to write women characters and enjoyed doing so, I didn’t know how to add another Sophie story into the structure. I would have had to create a space. That to me felt more than I wanted or had time to. The solution I came to, at every point in the different stories, was to make sure her character at every point was adding pressure to the story. I think of her as the secret second protagonist.

Like Raymond Carver’s work, “As Though That Were Love” relies on dialogue as Hartjes sorts his hot & cold relationship with his lover Simon, his new grief from the death of his mother, and loneliness. “He wanted it all, yet what he felt, what he really felt in the seat of his body, where his soul nestled and hummed, was the companionable happiness that comes with friendship.” Hartjes concludes that to really love someone is to decide not to hurt them intentionally. “As Though That Were Love” seems in conversation with “Anne of Cleaves,” where the protagonist’s ex returns to and does intentionally hurt them.

I workshopped “Anne of Cleaves” with Adam Haslett, and he was really nice and said a lot of great things. But he felt like I had let the ex-boyfriend back in to say something cruel, and that I was violating the story. And I was like, “Have you met men?” Yes, what he said to her was cruel and awful, but it felt appropriate to that character who doesn’t realize he’s being overbearing to the women that he says he loves. Of course he would try to gaslight her and say that his dying mother really loved her and they should get back together. It felt necessary to let him come back and say something awful to give her the affirmation that she deserved and needed.

I workshopped “Anne of Cleaves” with Adam Haslett, and he was really nice and said a lot of great things. But he felt like I had let the ex-boyfriend back in to say something cruel, and that I was violating the story. And I was like, “Have you met men?” Yes, what he said to her was cruel and awful, but it felt appropriate to that character who doesn’t realize he’s being overbearing to the women that he says he loves. Of course he would try to gaslight her and say that his dying mother really loved her and they should get back together. It felt necessary to let him come back and say something awful to give her the affirmation that she deserved and needed.

There’s a line in the book: “All there was to know was known by all there was to know it.” All the important information that needs to be known is known by people, so Marta in “Anne of Cleaves” and Hartjes in “As Though That Were Love” are asking why their lovers are suddenly trying to make them feel bad because their exes have suddenly come into this knowledge.

These are wise narrators. Sage, love sorters. They dive into the story when the characters need them most. In “Anne of Cleaves,” Marta is coming out but resists her new sexual identity when her thoughts twist between her past misery and her present happiness: “Maybe love was just believing something to be true because you’ve been told.” What do these stories have in common when trafficking love?

Something I found interesting in putting together the stories is similarities that I didn’t see before, often about love. In the beginning of the book there is this feeling of haunting in the characters and it follows them throughout the book and later transforms into a feeling of safety. That was only possible because of the order of the book that it ended up in. If it had a different order, it would have a different emergent thing. I feel when I read the book, a sense of being hounded by something to get to those last three or four stories. The characters start to feel more secure.

Everything you’re saying relates so much to our writing life. What am I willing to give up? Will I ever be secure? Am I willing to live a certain way to have agency every day?

I think the book in some ways is about agency. We have seen that happening in publishing. No one is like yes, thank you for disrupting the system. No one hands you a publishing deal because you told the truth. That’s what we do on the page.