I met Rebecca when she became an MFA student at the University of Michigan in the fall of 2010, at the beginning of my second year teaching there as the Delbanco Visiting Professor of Creative Writing. She was my student the following year, first in a full workshop and then as a thesis advisee—I was the second reader for drafts of what eventually became Rebecca’s debut novel, Unbecoming.

It was a learning experience for me as a teacher to discuss the project with her, and especially to talk about the evolution of the book’s compelling central character, Grace, whose small-town upbringing, intellectual awakening, and longing for a mother figure leads her to a series of complicated decisions. Grace’s story, about her role in a robbery that lands her longtime sweetheart and his two best friends in prison, showcases her talents as a valuator of both art and people.

Unbecoming was published today by Viking. Rebecca’s work has appeared in Subtropics (also listed as notable in Best American Short Stories 2014), the Toast, the New York Times, Jezebel, Hobart, the Hairpin, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. She received her MFA from the University of Michigan, where she was a postgraduate Zell Fellow. She lives in Michigan, where she is working on her second novel, Beta, and is a contributing editor for Fiction Writers Review.

Rebecca and I chatted via instant message about Unbecoming.

Interview:

V. V. Ganeshananthan: What are you doing to celebrate [pub day]?

Rebecca Scherm: Hmm, I don’t know! I hadn’t thought about it. Maybe I’ll buy a little chocolate cake and only share a tiny bit.

Chocolate cake connected to literary things or gluttony always makes me think of Bruce Bogtrotter. (Do you get that reference? I don’t know that we’ve ever talked Dahl.) I think that’s how your readers will be for Grace, like Bruce’s classmates, cheering him on as he eats the entire cake.

Right now I’m reimagining the whole novel as written by Dahl.

“Why, Gracie, here’s your golden ticket!”

HA!

It was such a pleasure to read it again and see the changes and additions you’d made. It’s a terrific book. Also: the ending! It kills me.

I am very proud of the ending, maybe prouder than I am of any other piece of my writing.

How long did it take you to find that ending? As I recall, there were other versions and dreams.

I tried to get to it several ways, but I was always trying to get to the same place. It was just a matter of finding the right route. I knew that the book would need to end with Grace alone in a moment, and that she would need to reckon with herself, by herself.

She’s a character who resists revelation about herself—as many of us do—and this would be the moment when she couldn’t get away from those realizations about herself, her life, what is meaningful to her.

What about writing that was hard?

When you’re writing a character who desperately wants to avoid knowing herself, and your whole point, as the writer, is to know her, it’s very hard to both pin her down and stay true to her. I needed to catch her during a rare, brief moment of stillness.

When you’re writing a character who desperately wants to avoid knowing herself, and your whole point, as the writer, is to know her, it’s very hard to both pin her down and stay true to her. I needed to catch her during a rare, brief moment of stillness.

But there’s something else about the ending that was important to me. I think readers (including myself) are trained to expect either redemption in the form of reformation—the “bad” character sets things right—or punishment. The endings that thrill me are the ones that refuse this choice. And I knew from the very beginning that I was writing a book that would make a different choice, that was about a different kind of redemption.

Yes, we had some really great conversations about that—and also about perceptions of femininity—while you were writing the book. I think people are even more likely to put that pressure on a woman; and of course we’ve also talked about that [Publishers Weekly] conversation between Claire Messud and her interviewer, about “liking” characters or wanting to be friends with them.

Because that ridiculous debate got so much air in the last few years—Claire Messud gave her very thorough dressing down, and then Roxane Gay did, and even the success of Gone Girl—I thought it was over. That I wouldn’t really have to fight that idea. Ha. HA! But yeah, in addition to the “likability” thing, I knew that because I was writing about the making of a “femme fatale,” I knew the expectation would be reformation or punishment. She’s a woman who does bad things and gets away with it, or so it seems from the outside.

It certainly does! What books or characters did you turn to as models? You and I have had a lot of terrific talks about image, both in books and beyond.

Unbecoming had three patron saints. First is A Judgement in Stone, by Ruth Rendell.

And what about that book did you love? And how did you come to it?

The first line of that novel is “Eunice Parchman killed the Coverdale family because she could not read or write.” I first read it in college—it was assigned as part of a seminar about media and literacy and Marshall McLuhan. I don’t remember anything about McLuhan, but that book stuck with me. I’ve read it so many times, and that first line became a guiding beat for me. She tells you everything, and the mystery and suspense come from wanting to know more. The first line of Unbecoming was modeled after Rendell. I will tell you that Grace is a liar, and you shouldn’t forget that.

And the second patron saint?

In the Lake of the Woods, by Tim O’Brien, which was also assigned reading, that one by Eileen Pollack in grad school.

Interesting, because Eileen also talks about overturning the chess board with endings.

Wait, what does she say about that? I should know this!

I’m pretty sure this is Eileen! She talks about if you are writing a story and if you feel stuck with the ending, like there is a decision to be made and two clear options, realizing that you aren’t limited to those. She gives her story “The Bris” as one example of a moment when she did this.

Yes!

This might even be a memory from a time I sat in on your first-year workshop. And I think you were up! A bit of this novel was up!

Yeah, that was me. And that’s it exactly. I’m not going to checkmate my characters, although they do that to each other. Then they’ll jump off the board.

Okay, anyway, so Lake of the Woods.

Okay, anyway, so Lake of the Woods.

If Rendell’s chill comes from her matter-of-factness, O’Brien’s comes from his elusiveness. He won’t tell you who’s “bad” and how bad. He forces you to decide, and what you decide says something about you and the way you see the world. It’s like a very sophisticated “Lady or the Tiger.”

I’m going to come back to these, but first I want to hear the third patron saint.

Scott Spencer, Endless Love. This was recommended to me by Jess Row and by Charlie Baxter. It’s an incredible novel about obsession, and I needed permission to obsess at that time. I was worried about looping back on fears and feelings and letting the character talk to herself too much. And it’s also very much about family envy and class, and has my favorite ending line: “And now for this last time, Jade, I don’t mind, or even ask if it is madness: I see your face, I see you, you; I see you in every seat.”

Now I’m wondering if my ending the book with Mrs. Graham was an unconscious imitation of this. Maybe.

I really like that ending line, and yet in POV it’s also so different from what you did.

The third-person keeps us at arm’s length, and that was the only choice Grace would tolerate.

I sometimes see the bones of things I’ve read and loved in my writing much later. Are there other moments like that in Unbecoming, that you recognize now that it’s done?

Unbecoming is littered with bits and bones from books I’ve loved. There’s a line that’s in homage to Mrs. Bridge, some crazy parts of Wuthering Heights and The Maltese Falcon, many traces of Highsmith, Du Maurier, Rendell, Spencer.

Did you know when you were doing it, or you only saw that later?

Only the Rendell and Connell moments were intentional. The others I saw later.

So, let me go back a minute to your patron saints, because you talk about matter-of-factness, and also elusiveness, and one of the things I thought you did most successfully was manage just an enormous amount of information, and the book is about morality and women and money, but it’s also on some level just a pure mystery for the reader.

For a lot of the book, you lead us along by telling us that Grace is a liar, and we’re in third [person], because as you say, that’s what Grace tolerates. And you parcel information out slowly, dropping these breadcrumbs of what has happened. This strikes me as a tightrope for you, and you walk it well. But how did you figure out how to do it? The structure that would permit those three patron saints to bestow their various favors on one book and work in harmony: disclosure, mystery, and repetition. (If those are fair words to choose.) There’s a huge amount of detail, and then also so much omitted in certain spots. And you’ve worked out how to make that a satisfying equation.

I moved information around constantly. And I almost always moved it up. That line about Grace being a liar crept further and further forward until I realized I needed to take the Rendell route: say it first, say it fast. And Eileen had told me something about suspense coming from what you DO know, not from what you don’t.

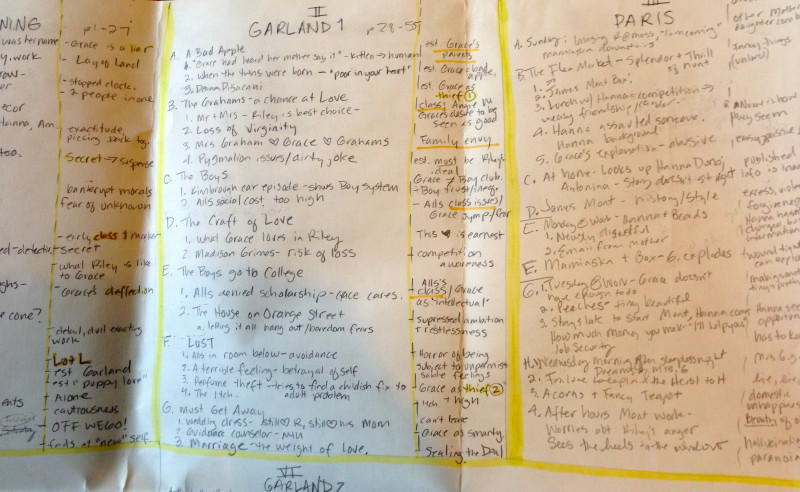

To manage the information, I had to make elaborate charts on my wall, only in pencil because they changed so much. I even coded pieces of information by what they were about thematically—sex, identity, money, “truth,” beauty, mothers, etc.

Do you still have the charts?

I have one. It helps me remember how messy this process was, how difficult. I need to see the record of that mess to believe that I can do this again.

WE HAVE TO DO THIS AGAIN? I’m kidding. Sort of.

HA!

More seriously, I ask if you still have the chart because I want to ask, on behalf of FWR’s readers, what are the odds that you would scan or take a snapshot of that and share it, redacting, perhaps, the latter half or two-thirds. I love looking at writer maps and charts.

Oh sure! And that will be easy, because the chart ends before the novel does. At a certain point, I didn’t need it anymore. I knew what happened.

Can you talk about the importance of place in this novel, and how it connects to money?

Well, I think when we’re kids, we imagine the whole world fitting into the economic spectrum we see in our everyday lives. Depending on where you live, the poorest people might be starving or they might be the one family without a swimming pool, and the richest people might be the ones with a newish Honda or they might be the ones with private jets. I think what we see in media doesn’t really jell for us as kids, not like what we see firsthand. But when you change the size of the world you see, your understanding of have and have-not changes radically.

To move Grace from a place where people are clustered pretty close racially, economically, and culturally to a place where they are not shakes her foundations, her assumptions, her sense of where she belongs.

Art offers so many beautiful metaphors for that in the book, from Riley’s paintings of Garland to Grace’s work on antiques. Like, for example, when she buys the Mont box—my God, so many specific and lovable objects in this book—and she has to paint each layer on and then sand it down so the previous layer shows through, but not sand it down TOO MUCH, because if she does that she’ll have to start over, which is this metaphor for the truth, and her specific lies.

Thank you! Yeah, and Mont is such an interesting character in his own right, this social-climbing Turkish teenager who renamed himself in Brooklyn. He and Grace are more alike than she realizes.

Or that part on page 70: “She would have to teach herself his gilding process in order to convincingly fill the chips and scratches. She relished every injury, running her fingers very lightly over them as if they were sensitive bruises. Each one was chance. She would repair them all.”

Art provides this great window into work, and money, and taste, and class, and also place.

These moments are as close as she can get to disclosure, even to herself. Sometimes the objects were born symbolic—what it might mean for a doctor to collect watches, for instance—but other times, the meaning or import of the object came later. The centerpiece is based on a real piece I saw at the decorative arts museum in Prague. They wouldn’t let me take pictures, and so I reimagined it, and it came to represent intricacy, fastidiousness, and fakery, but also, I think those four seasons are so quaint and cozy that they might represent “a simpler life” to Grace and Hanna (and to the collector), who are cut off from their origins. As for the Mont box—I don’t think he made such boxes. Unsurprisingly, he focused on grander furnishings. But I needed to make Mont portable, so I took some artistic license.

How did you pick art restoration and repair as her job? It’s SUCH a smart move. So much pleasure in the reading, in the expertise. And then it offers up these repeating symbols.

Her job was something I knew right away. She needed to be in the business of repair, of camouflage, and teetering on the edge of forgery. Her work would mirror her consciousness, and at moments when she is unwilling or unable to disclose, either to herself or to us, her work would tell us for her.

And of course I love those symbols of delicacy and preservation. Patina is such a potent symbol for authenticity, for having a past, ANY past. Like, what doesn’t have a past? The lesson that you should be suspicious of anything too clean.

Yes, when I was reading Nosy Girl’s interview with you and you said now that you’re older, you like to smell a little dirty… I thought of Grace, and the clean fake things she is able to spot precisely because they lack the marks of age.

Right. Accumulated wisdom is accumulated dirt. Or vice versa. And yet… Grace is so resistant to that idea for so long. It’s antithetical to the way many girls in the south are raised.

She sees only the divided self, toggling between Madonna and Whore as needed. Living like that would give anyone whiplash.

And Alls, that heartthrob, is living another version of that.

HA!

You know me. I have a thing for Alls. Always have.

Well, I do too. I will tell you something you don’t know about Alls, though you have known him for a long time.

TELL ME!

I got to a point where I couldn’t unlock him any further. Like Grace, he kept me at arm’s length. That’s the problem with these secretive characters. And then two things happened. First, I read the poem “You Can Have It” by Phillip Levine and it was like the heavens opened up. That was Alls—both the narrator and his brother.

And then, later (and speaking of Nosy Girl), I was reading Alyssa Harad’s memoir about perfume and I started thinking about how my characters smelled.

Maybe I should be embarrassed by this, but I am not.

I don’t see why you should be.

I smelled something that was Alls. It smelled like burning leaves, cedar, pepper, and orange peel. And I thought, ALLS, I KNOW YOU. The combination of Phillip Levine and one fancy cologne. Pretty crazy, I know.

It’s so exciting that your book is coming out. It was so exciting to open the envelope and hold it in my hands. Big chocolate cake, Rebecca.