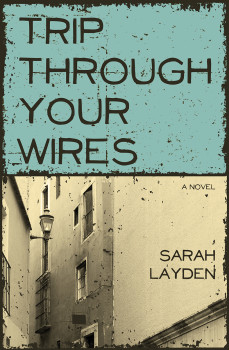

Perception and identity pivot upon crisis in Sarah Layden’s debut novel, Trip Through Your Wires, published in March by Engine Books. Through a masterfully-crafted dual narrative we follow the life of Carey Halpern—alternating between her as a self-conscious Midwestern college exchange student in Mexico and a disillusioned twenty-something living with her parents in Indianapolis seven years later. The novel shows us the dangerous power of the stories we tell ourselves. The mysterious murder of Carey’s beloved, Ben, on the night she sleeps with his best friend, leaves her with nothing but her own guilt and sorrow to make sense out of the seemingly random act of violence, until, nearly a decade later, the discovery of Ben’s passport in an abandoned suitcase sends her back through her memories to uncover the truth and find forgiveness. In this haunting first novel, Layden explores the blinding effects of desire, the fatal nature of romanticism, and how our personal fictions tell us who we are and what it is to be human.

I met Sarah in the fall of 2003 at the MFA fiction program at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. She came from a journalist background, was reserved, hard-working, and thoughtful. She’d left her steady job as a reporter, taking a risk that pitted desire against conventional Midwestern values—a double-edged guilt mechanism somehow imbedded in our cultural psyche—that viewed writing fiction as not only impractical but bordering on obscenity. How glad I was to have someone to share this with. She became and still is a dear friend and writing confidant. It was my great pleasure to interview her. Like Layden’s harrowing characters, I discovered how much my own self-conscious perspective had skewed the truth of our past.

Sarah Layden is the winner of the Allen and Nirelle Galson Prize for fiction and an AWP Intro Award. Her short fiction can be found in Boston Review, Stone Canoe, Blackbird, Artful Dodge, The Evansville Review, Booth, PANK, the anthology Sudden Flash Youth, and elsewhere. A two-time Society of Professional Journalists award winner, her recent essays, interviews and articles have appeared in Ladies’ Home Journal, The Writer’s Chronicle, NUVO, and The Humanist. She teaches writing at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and the Indiana Writers Center.

Interview:

Barney Haney: First off, big-time congratulations! It’s been a long time coming, my friend. Well done. Your book has occupied my mind with so many interesting questions—you wonderful, rotten bastard. Where does this self-consciousness stem from? Should we ultimately trust our perception? Are our identities mere evolving fictions?

Sarah Layden: Thank you. I really like your reading of the book, and I’m fascinated by perception and perspective and how and why our identities are shaped as they are. Not merely “coming of age,” which tends to be defined as a one-time thing or over a relatively short period of time: it seems to me that this is a process that happens repeatedly in our lives as we learn more about ourselves. One of the ways we get to know ourselves is through our interactions with others, and the things they show us about who we are. How they see our humanness, and how we see theirs. Gradually, our cores are revealed to ourselves in ways we might not have known, not without someone else to provide that perspective. Wrapped up in that, at least in the novel and often in real life, is the experience of knowing a person in a particular way, and finding out those beliefs were shaped largely by self-interested wants and desires—not an understanding of another’s true self. What then? How do we process—or re-process—the way we see ourselves? How do we make a break from filtering others’ experience of ourselves and begin to see through our own filter? These are questions I don’t necessarily have answers to, but they take up a fair amount of my brain space, and seem to find their way into much of what I write.

While working on Trip Through Your Wires, I came across a particularly apt quote from Nadine Gordimer. It prefaced a chapter in Margaret Atwood’s excellent craft book, Negotiating with the Dead. Gordimer writes, “Powers of observation heightened beyond the normal imply extraordinary disinvolvement: or rather the double process, excessive preoccupation and identification with the lives of others, and at the same time a monstrous detachment…The tension between standing apart and being fully involved: that is what makes a writer.”

And, I would add, that’s also what makes a human being.

You place the book’s backstory in the 90’s. What was your life like back then?

For me the decade started with junior high and ended while I was working my first post-college job, as a newspaper reporter. I was in college from 1993-97. Everyone jokes now about all the flannel, but truly, we were decked out in plaid. Those were such amazingly transformative years for me, which I think is one reason why I worked my way back to college, first for an MFA and then to teach. It wasn’t wanting to relive the time, but to be involved in the transformation that others were going through.

For me the decade started with junior high and ended while I was working my first post-college job, as a newspaper reporter. I was in college from 1993-97. Everyone jokes now about all the flannel, but truly, we were decked out in plaid. Those were such amazingly transformative years for me, which I think is one reason why I worked my way back to college, first for an MFA and then to teach. It wasn’t wanting to relive the time, but to be involved in the transformation that others were going through.

The decade for me is defined by music, songs and albums that are still imprinted on my brain: grunge acts; tours like Lilith Fair, H.O.R.D.E. Fest, Lollapalooza. Summers, I spent a lot of time going to concerts at night and working temporary jobs during the day—lifeguard, receptionist, data entry. At one job, they knew I was there for only a few months, so rather than train me to do more than answer phones, they suggested I bring reading material. I think I read between thirty to forty books that summer, including Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace. I filled notes in journal after journal, and made false starts on short stories that I would never finish. Back then, I secretly wanted to write fiction, but didn’t know how to get beyond a few pages without losing steam.

When did it stop being a secret?

Probably around the time I began thinking seriously about graduate school for the MFA. It gave me a tangible thing to point to: I am studying, I am writing, I am reading. Working toward a new thing. Even though I loved reading fiction and wanted to write it, I couldn’t rationalize it as practical. This is important as a Midwesterner, that your work be useful. Happily, my definition of “useful” has expanded quite a bit since my early twenties, to encompass all manner of things that feed the soul, though not necessarily the wallet and the stomach. But the heart needs to eat, too. It calls to mind the Bruce Springsteen song: “Hungry Heart.”

So I’d been flailing around on my own, trying to write fiction, and thought that in order to get serious, it would help me to flail in front of others. That turned out to be true.

This was August 2003 through May 2006. As I recall, you were married, you drove a three-hour round trip from Indianapolis to campus at least three days a week—from your house—and you brought your own lunch. You seemed, at least from where I sat, to have your shit together. Tell me your experience of those MFA years.

It’s funny to hear you characterize it that way; from the outside, it certainly does appear like someone who is put together. (I still frequently bring my lunch.) I’d been working as a newspaper reporter for six years, and starting the MFA was a huge culture shock for me. I very much tried to treat it like a job: I would put in daily hours, stay regimented in a variety of ways a la lunchbox and commute, and make sure I was wringing as much from this experience as possible. It was a leap to go from a salary to a stipend, a scary leap. And that’s where insides and outsides show such different things: my lunchbox sometimes had leftovers I’d rather toss, but that wasn’t economical. Or my reliable little Civic, racking up miles on I-65: the inside was littered with audiobooks and CDs and a week’s worth of cheap drive-thru detritus. Bags of books, just in case I needed them for class, because running home to Indianapolis wasn’t an option.

There were certainly moments of stress. But I loved the experience, which truly changed me. My own personal interior became remapped. Here was this literary life just there for the taking, with a whole program full of people who wanted to talk about writing and books and meet with authors and help you develop and ultimately publish your own work. I still feel lucky for the experience; Purdue is a fully-funded program, so I left grad school with no debt. In part due to my lunch-bringing habit, no doubt.

You brought the first chapter of Trip to workshop in the spring of ‘04. By the spring of ʻ06 you had a draft of the novel finished. Much happened in the following nine years before Engine Books published it. Poor Tom’s hair turned gray. Break down those eleven years.

When I first started experimenting with chapters of what would become the novel, for sure, I was writing to discover the story; I had no idea what it would be about. That’s kind of difficult to bring into a workshop, but I did get some valuable direction from readers. The first complete draft was my MFA thesis, a totally different book, bound and on a shelf not three feet away from me, that I will choose not to open. The next decade was about waiting. Waiting to hear back from agents. Waiting to hear from big publishing house editors. Rejection, but really encouraging letters. Revising, editing, revising some more. Making giant poster boards with multicolored Post-Its, trying to track tension and plot lines in the novel. Having a baby, and then another baby. I have not examined the photographic timeline, but this point, perhaps, is where my husband Tom’s hair turned more gray. Working as an adjunct at two universities. Sending out the novel myself to smaller presses. Waiting to hear from editors. Revising, again. Rejection, again. Coming close in a couple contests. Writing a YA novel, another full adult novel, and stories, poems, and essays. Sending the novel out for another round, this time to Engine Books, a new independent press which was developing an impressive roster. Waiting a year or so, and then, finally: acceptance. Followed by revision, of course.

When I first started experimenting with chapters of what would become the novel, for sure, I was writing to discover the story; I had no idea what it would be about. That’s kind of difficult to bring into a workshop, but I did get some valuable direction from readers. The first complete draft was my MFA thesis, a totally different book, bound and on a shelf not three feet away from me, that I will choose not to open. The next decade was about waiting. Waiting to hear back from agents. Waiting to hear from big publishing house editors. Rejection, but really encouraging letters. Revising, editing, revising some more. Making giant poster boards with multicolored Post-Its, trying to track tension and plot lines in the novel. Having a baby, and then another baby. I have not examined the photographic timeline, but this point, perhaps, is where my husband Tom’s hair turned more gray. Working as an adjunct at two universities. Sending out the novel myself to smaller presses. Waiting to hear from editors. Revising, again. Rejection, again. Coming close in a couple contests. Writing a YA novel, another full adult novel, and stories, poems, and essays. Sending the novel out for another round, this time to Engine Books, a new independent press which was developing an impressive roster. Waiting a year or so, and then, finally: acceptance. Followed by revision, of course.

A friend recently said to me, “You’re good at the long game.” That does seem to be the case.

I read some of these drafts. Your plotting really took hold. What clicked for you?

For a long time, I resisted the idea of making deliberate plot moves that seemed manipulative of the characters; the events as they occurred often were coincidental or seemed surprising in those drafts because they were a surprise to me. Eventually, I made peace with the artifice: all of it is manipulated, all of it designed to form a cohesive whole. And then I really began to figure out potential connections between characters and events.

Adult Carey lives on the verge of hardening, but pulls back at just the right moments, willing to accept her suffering, thus giving the reader hope. There are shades of Baldwin here. What other writers did you study while writing the book?

I’m glad to hear you read it that way. My reading life tends to be less about studying and more about devouring books and stories, to gain what I can through osmosis. Or reading just for the pleasure of sitting down and being in someone else’s head for a while. As you know, Alice McDermott is one of my favorites, and her quiet, reflective, beautiful way of conveying ordinary people and lives is something I greatly admire. I adore Elinor Lipman, whose books are both hilarious and tender. Willa Cather, Ian McEwan, Kate Atkinson, Junot Díaz, Dave Eggers: after reading one book by these writers, I’m compelled to read them all.

You made a mix tape for the ill-fated lovers in this story. The novel’s title is taken from a U2 song. What role does music play in your process?

Music! We could talk about this all day. Especially the angsty, alternative rock of the ’90s, or the a.m. radio of the ’60-70s. When I was a teenager, I made mix tapes all the time. Sure, it’s way easier to do digital playlists now, but I loved the process of putting songs on cassette: it took time and care, and it was a way to construct a story with music. To remind friends of memories, to share the songs you love, to convey your feelings in a way you might not be able to articulate.

I don’t listen to music when I write, but I do play music in most other waking moments.

On your acknowledgements page, you call Tom and the boys your “Home.” Describe a typical evening of your lovely chaos.

Careful on the driveway, where a toy lawnmower and several large sticks block access. No, don’t move the sticks. The sticks have been placed there deliberately for reasons we cannot know, and must not be tampered with. Come inside; just step over the one million pairs of shoes in the hallway. To the left you will find two young boys scaling the couch. The younger one, two-and-a-half, demands to be picked up, then flails from your arms to get back down. Then wants to be picked up again, even though he has just dislocated your shoulder. The older one, four-and-a-half, is busy constructing a machine out of a shoebox and stuffed animals. And then running through the house playing a harmonica. Neither will eat their vegetables at dinner. But they will sit on your lap for an hour afterward, reading books. Clean up, dishes, talking with your husband about the day, your conversation interrupted by kids scamming dessert because “I ate a good dinner!” Lies. Bedtime for the kids, and tonight, you write for a few hours afterward. Then collapse. Repeat the next day.

How do you balance—if at all—family, teaching, and writing?

Some days it feels very lopsided. Like a lot of women who work and have children, I struggle with guilt and wonder if I’m making the right choices for everyone involved. My philosophy-in-progress is this: family comes first, and I am part of the family. If anyone’s needs are ignored, there’s unhappiness. One of my needs is to write, and I try to do as much as I can while balancing quality time with my husband and kids. I’m lucky to have a partner who shares that philosophy and shares in the workload. It eases some of the pressure.

That said, there’s a stack of papers to be graded on my desk right now, along with an empty SpongeBob macaroni and cheese cup. (My lunch at 2:30 p.m. on a Friday. Note to self: aim for more balanced dinner.)

Where to from here?

Connections and disconnections are still an obsession, and are making their way into a new draft-in-progress. Another manuscript, a young adult novel, is about a high school volleyball team, and rumors gone awry about the sexual orientation of the players and coach. Writing it prompted me to join a rec league volleyball team out of nostalgia. The characters in my head have a much better vertical leap than I do these days.