I first met Avner Landes in New York City, where we used to play tennis in Central Park. While waiting for a court or after our spirited matches, we’d pass the time talking endlessly, excitedly, and passionately about writing, books, and politics while wiping the sweat off our brows and kicking crumbs of clay off our tennis shoes. I immediately recognized in Avi a kindred spirit with impeccable literary taste and sturdy moral convictions. Eventually we both left New York—I headed to Washington, DC, while he decamped to Tel Aviv—but we’ve continued our conversations via texting, FaceTime, and email. During some very troubled times, I continually feel reassured by Landes’s intelligent and sensitive readings of our cultural and historical moment.

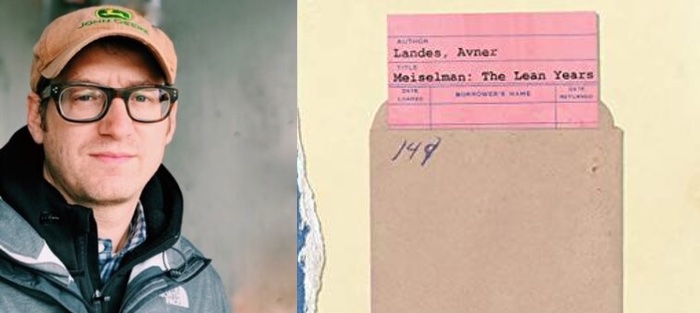

I see those same rock solid smarts and acute psychological insight at work in Landes’s debut novel, Meiselman: The Lean Years (Tortoise Books). The book is a boisterous feast of powerful prose, by turns hilarious and cringeworthy in its portrait of its nebbishy hero, an assistant librarian living in the Jewish suburbs of Chicago and trying to navigate his life’s disappointments to high comic effect. So much of this novel has lingered with me long after I finished reading its pages, including its sharp-eyed satiric portraits of self-important rabbis and authors, sharp-tongued women who rule their Illinois fiefdoms with iron fists, the book’s hapless protagonist, and above all, Landes’s somersaulting sentences that continually delight and surprise. It was my pleasure to sit down with Landes and delve further into the creation of this striking debut.

Interview:

Aaron Hamburger: Both because of your rollicking, muscular prose style and your cast of characters—Jews living in Chicago—your work has been compared to that of Saul Bellow. Could you talk a bit about his influence and the influence of other Jewish writers on you as you began as a writer? How do you see your work in relation to Jewish-American literature?

Avner Landes: There’s a story about Bellow I love. He was in Paris working on his third novel, and he was somewhat depressed with the results of his first two, which he felt were overly constrained and correct, written with the fear that wobbly syntax or unorthodox diction might betray his immigrant roots and prevent him from being accepted into the literary establishment. One morning, when out for a walk, he noticed a stream of water running along the curb and was struck with an epiphany: why couldn’t his writing have the same freedom of movement as the water? Suddenly, he thought back to his childhood, and the “rollicking” opening line of what would become Augie March took shape in his head.

When I first read writers like Roth, Bellow, and Malamud, there was the exhilaration of seeing my people in a book that was written for “everyone.” But, I took from these writings the wrong message: “Write what you are!” You have an obligation, in other words, to write about your people and community, an idea completely at odds with writing freely.

At the time, as someone who had spent a decade living in Israel, I felt expected to address “the situation.” This did not lead to good or joyful writing. It led to constrained and correct writing. As I began to read other great Jewish-American writers, like Stanley Elkin, Leonard Michaels, Grace Paley, Bruce Jay Friedman, along with many writers that aren’t Jewish, I began to correct my understanding of what it means to write freely. Now my writing is Jewish because I’m Jewish. My protagonist is an Orthodox Jew because I’m an Orthodox Jew. My novel takes place in Chicago because that’s where I was raised, but the next one may find my characters in New York or Tel Aviv, where I’ve also lived. Or it may take place in Bangalore because why not?

I’m very interested in the “Lean Years” part of the title of your book. Your protagonist Meiselman leads a fairly circumscribed existence. Why do you think Meiselman’s life is so “lean”? Also, can you talk about the significance of the Biblical allusion? It’s interesting that he seems to pin much of his hope for a fuller life on pulling off a successful event to promote someone else. What would a truly fuller life for Meiselman look like?

I’m very interested in the “Lean Years” part of the title of your book. Your protagonist Meiselman leads a fairly circumscribed existence. Why do you think Meiselman’s life is so “lean”? Also, can you talk about the significance of the Biblical allusion? It’s interesting that he seems to pin much of his hope for a fuller life on pulling off a successful event to promote someone else. What would a truly fuller life for Meiselman look like?

For starters, I’ve always thought that having the word “lean” in the title of a 400-page book is a solid joke. But the 36 years of Meiselman’s life leading up to the events in the book have certainly been lean. Here is a man incapable of authentic connections with other people, perhaps not even with himself. Every relationship is viewed through the context of his interests. Yet someone who lives with such a mindset is incapable of knowing his or her interests. “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?” Meiselman thinks at one point, ignoring the more crucial question of “If I am only for myself, who am I?” Who we are and what we want are revealed to us, Meiselman will learn, only through interactions with other people.

Meiselman’s chief concern at the book’s outset is that he is destined to lead this lean, impoverished existence. He wants to change the dynamic but can’t see how that might look. Reflecting on the biblical passage of Joseph interpreting Pharaoh’s dream, he recalls that the fat years anticipate the lean years, meaning there is no hope for him. But then he considers that he has it wrong and “it is the lean years that precede the party.” The event to promote the writer Izzy Shenkenberg is the culmination of Meiselman’s course to unleash his aggression and liberate himself from his lean existence. I think his struggle to move the needle in a more favorable direction is rather ordinary. Most of us think our lives can be a little fatter, a little fuller, and we are constantly identifying near-future moments as potential breakthroughs, the crossroad where we’ll set old demons aside and chart a redemptive path. We fail or find a modicum of success, and then we identify the next moment for a possible breakthrough.

Many of the women in the book seem to occupy a position of power, especially compared to Meiselman. I’m thinking not only of his boss, Ethel, but also his wife and even supporting characters like the pink-haired woman in the library. They speak their minds, have firm ideas about what they want, and often they go after it. Meisleman, on the other hand, seems to struggle with speaking clearly and owning his masculinity. Could you talk a bit about the women in this book and how gender plays a role in the story?

I’m pleased and relieved that you noticed the strength of the women in this book. Meiselman is an unreliable narrator, especially early on in the book. His obsessions prevent him, and by extension the reader, from getting a clear picture of the other characters, especially the women. Additionally, the self-generated noise in his mind inhibits Meiselman from analyzing what his obsessions might suggest about who he is and what he wants. Early on, a lot of these obsessions are tied to ideas of masculinity, gender roles, the way people are “supposed” to act, and they frustrate any attempt by Meiselman to get at his essence. What he begins to understand, as the book progresses, is that the purpose of gender roles—and other conventional orthodoxies—is to exert control over how we think of ourselves to prevent us from thinking about ourselves in an honest way. There’s a Douglas Coupland line from Life After God that has stayed with me for years: “I think about how hard it is . . . to reach that spot inside us that remains pure that we never manage to touch but which we know exists . . .”

The women characters in the book succeed in drawing close to that “spot.” The men—Meiselman’s father, his brother, Shenkenberg—not so much. They put up barriers—orthodoxies and rituals—around the “spot.” Meiselman, at some point, in his way, appreciates what these women have accomplished, and he wants it, too.

Your story has so many wonderful comic interludes, though my favorite has to be when Meiselman takes his wife’s underwear to the rabbi so he can inspect the size of a spot of blood on it, thereby giving the Meiselmans permission to have sex (since Orthodox Jews aren’t permitted to have sex when a woman is menstruating—do I have this right?). So many writers of contemporary literary fiction have either very limited humor in their work or a kind of restrained, ironic wit in their writing, but you really dare to go full-on screwball. What’s your take on the use of humor in contemporary literary writing, and can you talk about how you use it in your work?

The inspiration for the main character, Meiselman, came in part from personal dissatisfaction with the way I was using humor in my earlier work. The narrators of these never-to-be published writings were puckish, ironic, smarter than everyone, and willing to go only so far in their bad behavior. Anything egregious or cruel was reserved for other characters. This hesitation came from a fear that people reading my protagonists might assume that I, the author, as an extension of my protagonist, is immoral and has the wrong politics. Maybe this approach to writing reflects a trend in contemporary fiction. I can think of examples. Yet reading some great comic writers made me appreciate the thrill of dragging one’s characters through the mud, writers like Stanley Elkin, Bruce Jay Friedman, Nell Zink, Ottessa Moshfegh, to name a few.

Jaime Manrique, a former teacher, would occasionally yell at our class when dissatisfied, “This reads like life, not like fiction!” This line plays in my head as I work, and my goal is to make fiction that doesn’t read too much like “life,” stories that repress the urges and impulses of characters. Most of us walk through life knowing that the banal utterances of others and ourselves are loaded and revelatory, but for convenience and comfort, we stay quiet and take everything at face value. A story begins to reads like fiction when the author succeeds in extracting and parading buried versions of people and allows these liberated selves to rub up against one another. A barely noticeable peculiarity in real life ends up defining a character in fiction. It happens to be that this parading is usually funny and grotesque and sad.

People, for example, ask if the scene of the rabbi checking the blood on Meiselman’s wife’s underwear is an accurate portrayal of how a rabbi would check a woman’s underwear. That question doesn’t interest me. Rav Fruman wants to check the underwear this way, so that is how he proceeds. A scene with a rabbi performing a typical, true-to-life “inspection” would read like “life,” turning the scene into one that perhaps questions the role of women in religious Judaism. An important topic, no doubt, but it’s not my department or interest, and it’s not why I read or write fiction. There are more insightful works to read on that topic.

I noted more emphasis on religious practice in the novel than on religious faith. Maybe that’s my misreading of it, but I wondered what is the book’s point of view on traditional religion and faith. It seems like the book wants to poke fun at any number of institutions and religion seems among those (again, the prime example being the rabbi underwear inspection scene). What’s your take on the issue of religion and faith in this novel? To what degree are they separate?

Again, as I mentioned in the previous answer, I’m not interested in exploring larger religious issues or commenting on the virtues of religious communities. Nevertheless, I’ve created a character with a specific religious attitude that probably mirrors the beliefs and practices of many in his Modern Orthodox Jewish community. Religious observance and religious faith play a major role in Meiselman’s life, and early on in the book, after a series of coincidences put him in an uncomfortable position, the reader gets a sense of his religious outlook and how it steers his actions. “Fate, destiny, he has always thought of such ideas as heretical, the beliefs of people who want to see God as a personal benefactor, a pal.” Yet Meiselman undoes this affirmation of humility in the next sentence. “But maybe God does, every now and then move away from big picture matters to involve himself—itself—in more minor matters like the life of his humble servant Meiselman.” The first sentence expresses the humility the religion obligates him to display. The second sentence conveys how Meiselman actually feels, which is that God is, in fact, his personal benefactor, his pal. Meiselman as a religious person is mindful, especially in moments of rebellion, to use the language of religion to justify his thoughts and actions.

Religious belief and religious observance aren’t interchangeable, as many people mistakenly assume. Rather, they are two things that play off one another. The religious person rationalizes breaking the rules of observance by employing the language of religious belief, like the scene where Meiselman rationalizes eating the chocolates that may or may not be kosher. Meiselman’s god isn’t one pushing him toward the better angels of his nature. Instead, it’s a god that pushes him to a life where everything is permissible.

The plot of the novel is focused on the arrival of Shenkenberg, a literary star who’s giving a talk at the library where Meiselman works. Sheneknberg’s own celebrity depends on his book about another writer of sorts, the famed Rabbi J-. To promote the event, Meiselman’s pitching local journalists, trying to get them to cover the story. All this, plus the fact that the book is largely set in a library made me think of what this book has to say about literature and the literary industry. Could you talk about this book’s point of view and maybe yours too about the business of books and book promotion, particularly now as you’re engaging in it yourself?

At one time, a chapter of Shenkenberg’s “controversial” book appeared in the novel as a novel-within-a-novel. The Shenkenberg chapter was an unpublished story I’d written close to twenty years ago about a man in his late twenties who travels with a group of senior citizens to Poland on a Jewish heritage tour. The writing in that story—and this goes back to how I answered your humor question—is a good example of a type of humorous writing that came to displease me. At the time, I thought it was funny. Readers—more accurately, fellow workshop participants and teachers—thought it was funny, too. Everyone could laugh along with the puckish narrator who scratched at his hemorrhoids in the crematorium of a concentration camp. Eventually, I realized that the story was nothing more than an unoriginal cultural commentary on how Jews remember the Holocaust, even if it was an irreverent take. But what was on the page didn’t cause any discomfort to readers because it wasn’t written with hesitation or reservations. It was low-hanging fruit. In the end, I removed this novel-within-a-novel from the book when an agent suggested that it was superfluous. He said that a reader knows Shenkenberg’s style of writing just from the description of him. And he was right. So if Shenkenberg’s writing is my old writing, then maybe Shenkenberg is what I once thought it meant to be a writer.

Some of the inspiration for Meiselman: The Lean Years comes from a period of my life when I was working as a coordinator for a creative writing program. One semester, the program hosted the great Steve Stern as a visiting writer, and I remember we were walking on campus to some event when he suddenly turned to me with a look of real angst. He asked if I knew what time we’d be done since he had to get home to see whether S— was going to be okay. I asked who S— was, what sort of problem he was dealing with, and whether the program could be of any help. S—, he told me, was a character in the book he was writing. Well, they tell you to write the book you want to read.

Book promotion has its ups and downs. It’s a lot of waiting around for other people’s validation. Maybe you get some love, or just get a punch to the gut instead. Either way, the next day you find yourself waiting again. In the end, all of the waiting is a terrible waste of time. I’d rather be stressing over what’s happening with my characters. Easier said than done but, no question, the most gratifying activity for a writer.