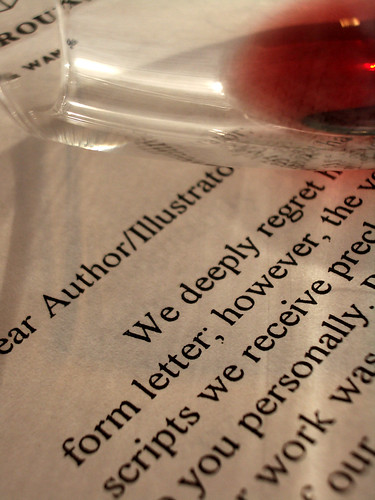

I save rejection slips. In graduate school, someone mentioned an acquaintance who had wallpapered her bathroom with them, and I liked that idea. There was something honest and humbling about it. So when I started submitting my own stories to literary journals, I saved the rejections, imagining I might do the same one day. It would be a necessary complement, I imagined, for a living room mantel cluttered with prestigious awards, framed reviews, and my many excellent books.

I’ve long since backed off both the wallpapering and the cluttered mantel, but I haven’t stopped saving the slips. And I have no idea why. More than once I’ve decided to throw them all out, but I never follow through. I keep stuffing them into the shoe box that holds my diplomas and immunization records and other important documents. I’m not a hoarder; if anything, I’m the opposite. I love open space and bare surfaces. I throw out birthday cards and valentines without remorse. But I can’t bring myself to recycle those rejections.

Most writers I know keep some sort of spreadsheet or running count, if not the actual letters of refusal. Some, I’ve heard, actually print the emails from online submissions. In the Mar/Apr issue of Poets & Writers, Jennifer Wisner Kelly describes the “Folder of Failure” in which she collects her rejections, and in the Nov/Dec 2011 issue, M. Allen Cunningham describes receiving a story’s sixteenth rejection, then quickly adds that another story “recently garnered its thirty-seventh rejection” (his emphasis).

Most writers I know keep some sort of spreadsheet or running count, if not the actual letters of refusal. Some, I’ve heard, actually print the emails from online submissions. In the Mar/Apr issue of Poets & Writers, Jennifer Wisner Kelly describes the “Folder of Failure” in which she collects her rejections, and in the Nov/Dec 2011 issue, M. Allen Cunningham describes receiving a story’s sixteenth rejection, then quickly adds that another story “recently garnered its thirty-seventh rejection” (his emphasis).

We writers, it seems, are enthralled by our own failures. And as Kelly and Cunningham demonstrate, we love to publicize them. Post on Facebook about how many rejections you’ve received, and see how many of your writer friends comment, “You think that’s bad?” and then give their own numbers. It’s a reflex. We can’t help it. When a friend emailed me last week about getting an acceptance after twenty-seven rejections, I congratulated her. Then I told her I’d just published a story that had received more than fifty rejections, and I was still submitting one that had more than seventy. And I’m sure many of you are rushing down to the comment box right now to say, “You think that’s bad?”

Why do we do this? Rejections don’t exactly reflect well on our work. Writers are fond of naming some great story that suffered some unconscionable number of rejections, and we take heart from those examples, but in general, great stories don’t get as many rejections as mediocre ones. The reason is self-evident.

Do they give us a sense of legitimacy? Before my first rejection, I’d heard about all the discouragement and disappointment writers faced, so getting my first dose of it made me feel like a real writer. This was the necessary suffering, I thought. But that sentiment has long since dried up. These days the acceptances make me feel like a real writer, and the rejections chip away at that feeling.

Are we simply masochists? Our raw materials, after all, are conflict and suffering. If something doesn’t go wrong, it probably isn’t worth writing about. Does that mean we’re keen for conflict and suffering in our own lives? Maybe, but I don’t think we brag about other sources of pain in the same way: You think that’s bad? Listen to how many grandparents I’ve lost! Listen to how many lovers have cheated on me!

Are we simply masochists? Our raw materials, after all, are conflict and suffering. If something doesn’t go wrong, it probably isn’t worth writing about. Does that mean we’re keen for conflict and suffering in our own lives? Maybe, but I don’t think we brag about other sources of pain in the same way: You think that’s bad? Listen to how many grandparents I’ve lost! Listen to how many lovers have cheated on me!

Are we commiserating? One-upping each other? Making pleas for sympathy? Showing off our perseverance? Chronicling our writing lives? Enacting some kind of revenge? Maybe, maybe, maybe. All these possibilities seem partly right, partly wrong. The truth is, I don’t have an answer. To me the phenomenon is a mystery, as inscrutable as the editorial whims and judgments that cause it. Maybe that’s why I can’t seem to let it go.

Further Reading:

- Waiting three years… for a rejection

- Subscribe to Poets and Writers magazine at the special super-low FWR rate!