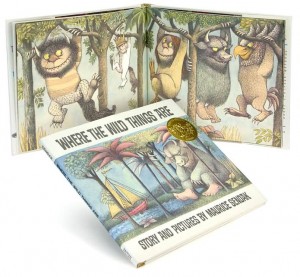

Maurice Sendak’s picture book Where the Wild Things Are is nearly 50 years old, but the release of Spike Jonze’s film adaptation has sparked a resurgence of critical interpretations of the story. A sampling:

On the Oxford University Press blog, philosophy professor Stephen T. Asma ties our love for Where the Wild Things Are to our fascination with other monsters–“zombies, vampires, and serial killers”:

As the movie’s trailer reminds us, “Inside all of us is a wild thing.” And in our therapeutic era, we generally accept that it is good and healthy to visit our wild things –to let them off their chains, let them howl at the moon. You can also taste some of this Romanticism in the recent relish of the Woodstock anniversary, with its celebration of noble primitivism. But the hippy view of “the wild” is quite sunny, whereas Sendak (who lost family during the Holocaust) wanted to acknowledge some of the darker aspects of uncivilized life (even, or especially, through the eyes of a child). Despite these darker notes, however, Where the Wild Things Are still affirms the idea that danger, at least in small doses, is good for you. And this latest fascination with beasties, together with the approach of Halloween, reminds us that we have a love/hate relationship with monsters generally. We are simultaneously attracted and repulsed by them.

At The Millions, Emily Collette Wilkinson looks at WTWTA through a Hobbesian lens:

And so we have in Wild Things Hobbes for children and a Hobbesian child hero (“no Arts; no Letters; no Society…the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”) Max seems constrained by the civilized domestic world in which we find him in the first frame. Sendak reveals Max’s confinement by making his first illustration only four inches by five and a half, with three-inch, white margins; the story’s illustrations grow progressively larger as Max’s wildness escalates and he is finally sent to his room. Only when the imaginary forest realm of the wild things has totally overgrown his room do the illustrations take up the whole of each page—as if to say that only when Max enters his imaginary world of unadulterated wildness and savagery do we see him fully.

New York Times columnist David Brooks uses WTWTA to illustrate the psychologist’s view that “we are a community of competing selves” and meditates on the value of creative work–sort of:

In the psychologist’s version, the good life is won indirectly. People have only vague intuitions about the instincts and impulses that have been implanted in them by evolution, culture and upbringing. There is no easy way to command all the wild things jostling inside.

But it is possible to achieve momentary harmony through creative work. Max has all his Wild Things at peace when he is immersed in building a fort or when he is giving another his complete attention. This isn’t the good life through heroic self-analysis but through mundane, self-forgetting effort, and through everyday routines.

And finally, on Huffington Post Books, the voice actors of the film reflect on the book that inspired it all.

[[Lauren Ambrose]]: That’s exactly what we all do, trying to solve our problems. People lying on couches and going to therapy and trying to access this vast unconscious to allow it to help us solve our problems. That’s what the book is about. One of the things it’s about to me is that this kid goes and is able to access his vast imagination, childlike imagination, which is what we all try to get back to, to help him learn how to be in the world and learn how to solve his problems with his mom. It’s also about how success and fame and being the king is nothing compared to family, community, soup and your mom. That’s the last page, that soup that’s still hot.

Read more here.