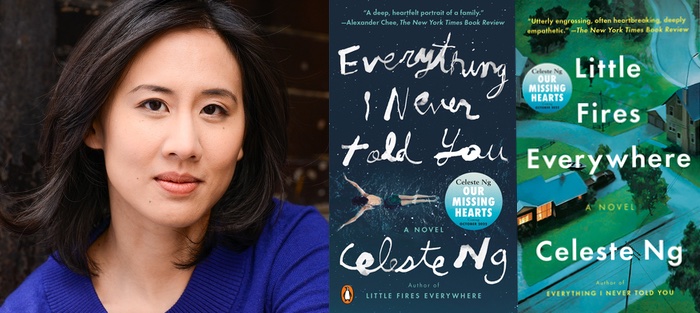

Editor’s Note: For the past several months, we’ve been celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts. We conclude the series with Celeste Ng’s essay on why fiction matters. This essay was originally published on October 5, 2008.

If you want to see how much people care about fiction, try reading on public transportation. A few years ago, I boarded a bus with Graham Swift’s Waterland in hand. The woman next to me asked if it was any good, and I told her I was only two chapters in but a friend had loved it, and Graham Swift won the Booker Prize for Last Orders. She blinked. Then she said, “See, I’m looking for something to read. I used to read a lot of those—what do you call them—” (She groped for the word.) “Fiction books, that’s it. I used to read a lot of those fiction books. But now I mostly just read romance.”

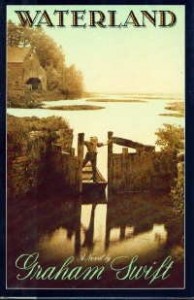

She asked what my book was about, and I explained: a history teacher in England, how the events of his youth and the history of the land fed into the tragedy of his present. I could see her eyes losing focus, her attention drifting to the Ann Arbor streets outside the bus window. But then she saw the cover of the paperback. She snapped to attention. “Is he tied up?” she asked, an unmistakable note of titillation in her voice. “With a bag on his head?”

The cover showed a black-and-white photograph of a man standing in a dinghy, arms spread to open the gates of a lock, the straw hat on his head concealing his bent-down face. It was the spring of 2004 and one particular story had taken over the news. “Oh, no,” I tried to explain. “You see, the book is about a lock-keeper. In the Fens.” She stared. “A man who works on the river. In England. He’s opening the gate so a boat can come by.” Still the blank stare. “It’s fiction,” I reminded her. Nothing. “It’s made up. It has nothing to do with Abu Ghraib,” I said finally, and she turned away, disappointed and profoundly disinterested.

The cover showed a black-and-white photograph of a man standing in a dinghy, arms spread to open the gates of a lock, the straw hat on his head concealing his bent-down face. It was the spring of 2004 and one particular story had taken over the news. “Oh, no,” I tried to explain. “You see, the book is about a lock-keeper. In the Fens.” She stared. “A man who works on the river. In England. He’s opening the gate so a boat can come by.” Still the blank stare. “It’s fiction,” I reminded her. Nothing. “It’s made up. It has nothing to do with Abu Ghraib,” I said finally, and she turned away, disappointed and profoundly disinterested.

I don’t fault her for being unfamiliar with the Booker Prize, or for reading romances, or for zoning out during a stranger’s synopsis. But her insistent injection of Abu Ghraib into the novel, her apparent classification of romance as true, and most of all the way she said fiction as if it were a foreign word: these things still rankle. They remind me how many people have no interest in fiction and almost no concept of what the term “fiction” means.

As a writer of fiction, I worry about this. More troublingly, many people seem to have trouble distinguishing between fiction and fact. Think about how hard it is for some to separate Stephen Colbert, the character, from Stephen Colbert, the comedian behind the persona. This may explain how Colbert got invited to speak at the White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner in 2006, and why the silence in the room was so very icy. If you expect an arch-conservative political commentator who worships the president and what you get is a liberal political-satirist-comedian mocking you—both for your beliefs and because you were dumb enough to think his character was real—you’d be a little frigid too. Yet the White House Press Corps’s inability to disentangle fact from fiction suggests that the woman on the bus is not an anomaly.

This might also explain why some memoirists have problems with making things up. Thanks to Oprah, James Frey might be most infamous, but later memoir writers have gone far beyond falsifying a few details. Recently Margaret Seltzer became the latest to admit fabricating her life story—in this case, the entire thing. In the book, she’s a half–Native American, half-white foster child named Margaret B. Jones who runs drugs for the Bloods; in real life, she has a comfortable home, no such history, no tattoos. As a false memoirist, she garnered a glowing review from Michiko Kakutani, an hour-long interview on NPR, and a hefty advance. A day after the news broke on the New York Times website, readers had logged in nearly six hundred comments. Many were outraged. “Shame on this young woman,” Richard Black, from California, wrote. “Shame on her parents and friends for helping foist this scam on the reading public. How can any reader of this farce, this story of deceit, not feel disgusted and betrayed at how far some will go in their pursuit of coins and fame. Integrity is in intensive care.”

This anger is easy enough to understand. The true memoir writer promises to tell you the truth and does it. The false memoir writer says, “I am going to tell you the truth” but then lies, and it’s the lying while pretending to be honest that so offends people. It’s a kind of breach of contract, or at least literary false advertising. No one likes feeling duped, especially memoir readers, who like their stories steamy and scandalous and, above all, “true.” A few summers ago I sat on a bench in Central Park and listened to the young I-bankers and consultants behind me on their lunch break. They were talking about Augusten Burrough’s latest memoir. “It was just so much better because it was true,” one of them said—like the woman on the bus, titillation thrumming in her voice. “Because all those awful things really happened.” Somehow, the factuality of the story amped everything up, made it more appealing and powerful.

But a surprising number of comments took a different tack. A man from Minneapolis wrote, “I’m pretty dumbfounded about this. Not that not Margaret B. Whoeversheis wrote a good story and tried to pass it off as true. To that I say, who cares. Every good storyteller I ever knew did this. I’m dumbfound by all the people that seem to care so much [about] this.” Another commented, “gotcha. who cares really? the reviews seem to indicate that it’s a good read and a compelling story. Are we going to rip apart jack kerouac because his story isn’t all true.” And one commenter from Texas was even more succinct: “WHO CARES?????????????”

Their comments suggest the same confusion between fact and fiction as the woman on the bus. Isn’t the story itself all that matters? Why should we bother to distinguish fiction from non? And both types of comments—the shame-on-yous and the who-cares—imply a larger question: why do we need fiction, anyway? Isn’t a story just better if it’s true? Isn’t a story that’s made up less powerful, less gripping? What difference does it make if a story is fact or fiction?

It makes a great deal of difference. The power of memoir lies in its factual truth. It is the account of one who has lived through something horrific, whether it’s addiction, cancer, or genocide. When we pick up a memoir, we expect it to be true, so we accept the author’s word for things that would otherwise seem far-fetched: Under the influence my mother gave me away to her shrink or My sister’s hands were cut off in front of me. These are the statements of a witness, told in the first person, with that powerful I of testimony. We take the stories as truth because the teller swears that’s what they are. And that’s why “just a good story” isn’t quite enough. In memoir, the author’s integrity is crucial: without it, the author is lying under oath, but with it, we give credence to even the most unbelievable horrors.

In fiction, the author has no such head start. Unlike the memoirist, who promises to tell the truth, the fiction writer says upfront, “I am going to tell you a lie, but at the end you will feel that it is true.” He or she is a kind of magician who makes sure you know that the flames are only an illusion before letting you burn your fingers in them. Every event, every character, must be made real by the author’s skill. It is a tricky balancing act, because the fiction writer aims for simultaneous belief and disbelief: a belief in the essential trueness of this world—that these people could exist, that these events could have happened—with a full consciousness of their falsehood.

By its nature, memoir says, This happened. This really happened and I must tell it. It’s spurred by a desire to go on the record, to be heard. But fiction’s role is essentially persuasive. It forces you to start from a position of disbelief by announcing its own fictitiousness. Then it transforms you into the literary equivalent of a sinner seeing the light, a prodigal son whose faith is stronger for having doubted and been redeemed. You don’t question a memoir; you believe it’s true when you pick it up. But you are told from the beginning that fiction is untrue. It depends on its own power to convince you in spite of this knowledge, and that belief, when it comes, is a complete transformation. And this is why we need fiction.

In a recent interview, novelist Ian McEwan spoke the words that became FWR’s mantra: “Imagining what it is like to be someone other than yourself is at the core of our humanity. It is the essence of compassion, and it is the beginning of morality.” Memoirs, when true, allow us to do this. They let us walk in shoes of those who’ve experienced things we have not. Like recordings of Holocaust survivors and documents of war crimes, they preserve the truth for posterity and let those who need to speak have their say. But memoir has its limitations, too. Memoir says, I won’t believe it until someone tells me that it really happened. It demands proof, testimony from the witness-box, a concrete example; it is retrospective, focused on fact, on what did happen.

Fiction says, I believe that this could happen. It is prospective, focused on possibilities. It opens us to the possible, the hypothetical, rather than binding us to the actual. And this, more than anything, is why true stories alone aren’t enough, why we should recognize fiction and read it, why fiction is valuable. Without fiction, we might end up like the woman on the bus, unable to muster interest in anything that isn’t a True Story, that doesn’t come with shocking photographs. We would have no what ifs, only what dids. We would have nothing but the actual. And if we believe only in the actual, how small our lives would be, how limited and mean our humanity, to demand proof before we believe or conceive of suffering, loss, or strangeness.