“One is not born a genius, one becomes a genius.”– Simone de Beauvoir

The words slipped out of my mouth during an undergraduate nonfiction workshop. A previously unremarkable student had just produced one of those “get it right on the first try” pieces I’ve never been able to do myself: a four-page lyric essay about walking through her now-abandoned childhood home. Her fellow students in the circle had almost nothing to say; one corrected a couple of typos, another said it was terrific, and the rest stared at me.

“I think you’ve just got to trust genius on this one,” I said.

My students sat silently for a moment, trying to figure out whether I had just called the writer in question a genius, and in that silence I realized how true those words were. Sometimes we simply have to trust genius enough to know when it strikes and leave its handiwork alone, whether it comes in the first draft or the tenth. I wouldn’t call this student “a genius,” and she never again wrote work of comparable depth for my class. But she did tap into genius terrifically in that one piece, which got me thinking about the nature of that very weighted word and the misguided ways we use it.

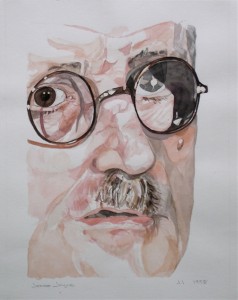

James Joyce, by Joel Isaacson

Dictionaries offer many meanings of the word genius: a spirit of a given time or place (the genius of post-WWII Paris), an attendant spirit (usually in the plural, genii), an inclination or aptitude (a genius for administration), etc. Most typically, though, we think of it as some kind of extraordinary creative or mental force, and more often than not we use the word as a label to indicate someone who possesses that force. Mozart was a genius. Joyce was a genius. Picasso was a genius. By using the word this way, we actually restrict the power of that extraordinary creative or mental power by acting as if it resides within the individual upon whom we bestow the label.

In the creative world, the term makes hierarchies simple. So-and-so is proclaimed a genius, many other so-and-sos are not, and we give our attention and accolades to those who have earned the moniker. The same can be said for individual works; even if we as a culture are not willing to bestow the title of genius on a given artist, that person is still capable of making a work of genius from time to time. We bestow the label carefully, often using it in bandwagon fashion, only after others have done the same. (It’s quite uncomfortable to proclaim someone a genius and have no one second your motion.)

But this is such a limited way to use a wonderful word that many, many writers will experience in their lifetimes. You’ve probably experienced it, I’ve experienced it, and people we know have, too. It comes in flashes and then leaves, because you don’t possess genius—not even if you happen to be declared one. Instead genius inhabits you, enables you, fills you. I think the creative world would be better off by far—perhaps less selfish and competitive—if we embrace a concept of genius that envisions it as free-floating and collective, rather than bound up in the individual. Genius is something that strikes us, something we occasionally tap into unaware. We should be more concerned with this timeless, incomprehensible force that inhabits writers than with the accolades we use the genius word to bestow.

As writers, we should be keenly aware that our genius is collective because we share our language with others—we each have a word-hoard that others tap into every second of the day. Our sentences resemble prior sentences, our characters resemble prior characters, our plots resemble prior plots. Legendary geniuses and everyday writers alike draw from the same well, the same word-hoards given to us by our cultural histories. Many people are capable of dipping into that well, of drilling into the aquifers beneath, because the water within it belongs to everyone.

Following my own logic here, it should follow that anyone is capable of creating a work of genius. And I think that’s true. We never know when genius is going to strike, whether in ourselves or in others, and our experience of literature—both as consumers and producers—is far richer when we are receptive to genius and feel that it can strike at any moment. Genius can arrive when we pick up a pen, when we pick up a literary magazine, when we pick up a manuscript that no one else has read. This concept of genius can be a liberating thing, because there’s no pressure on us to be one; there’s only an invitation to participate in genius, as so many before us have done and will do in the future.

Following my own logic here, it should follow that anyone is capable of creating a work of genius. And I think that’s true. We never know when genius is going to strike, whether in ourselves or in others, and our experience of literature—both as consumers and producers—is far richer when we are receptive to genius and feel that it can strike at any moment. Genius can arrive when we pick up a pen, when we pick up a literary magazine, when we pick up a manuscript that no one else has read. This concept of genius can be a liberating thing, because there’s no pressure on us to be one; there’s only an invitation to participate in genius, as so many before us have done and will do in the future.

It’s a much better world, isn’t it, when the spirit of creative genius is something we can all dip ourselves into rather than something we scrape and claw to get?

But despite this “universal access” to genius—which I hope you’ll agree paints a more complete, flexible, and lively definition of the word than its staid, competitive, traditional use as a label—we still have to account for the fact that some people are… well, better writers than others. Some people can tap into that collective genius with more frequency, while others hit a gusher once and never see it again. We’ve all met (or perhaps we are) writers capable of absolute brilliance who can’t quite “get things together” enough to create a whole, integrated, recognizably strong work of literature. That’s because drilling into the collective genius is one thing, and bringing work back out of it is another.

The problem is that accessing the collective genius of our species (which requires humility, boldness, or both) is never in itself sufficient for making literature. It’s crucial to creative success, sure—and by success I mean not work that is noted critically or commercially, but work that has creative integrity—but one doesn’t create a lasting literary work without a sense of self-mastery and/or intense focus, which may be more difficult to achieve than forays into collective genius. The journey back and forth into genius is like the journey Orpheus makes to the underworld and back in Greek mythology. It’s much easier to go to the underworld in search of the prize we seek (either Eurydice or a literary masterpiece) than it is to haul that prize back up to the surface.

Orpheus and Eurydice

How to get that prize back up is what we try to learn through our own writing practice and our interaction with other writers, living and dead. I wish I could tell you what the secret is, but I can’t because (a) I’m not sure myself, and (b) every single work needs to be finessed out of the collective genius and into the light of day in its own unique fashion. I’d like to say that there’s a common denominator or two, some things that all great works share, but I’m not even certain of that. Humility in the face of one’s craft is a candidate, but many works of genius have been penned by exceptionally arrogant authors without a shred of humility in them. Great skill is another, but skillful writers are a dime a dozen; any hack can make the words pretty, so why connect creative genius with mere skill?

Orpheus and Eurydice. Painting from 1806 by C. G. Kratzenstein-Stub, 1793-1860. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

The more I think about it—and I think about it a lot, because I want my fiction to be the best it can be and want my efforts to be pure—the more I think that the common denominator among great literary works is their authors’ willingness to give things up in order to pull those works, whole and unfettered, out of the collective genius where they reside. What gets given up depends on the author and the book. It could be family, love, money, security, traditional fame—any number of external things. It could be sanity, past beliefs, health, hope, fear—any number of internal things. Maybe the great works we lionize are united by having authors who are willing to pay whatever price genius demands of them for the right to haul that work up from the collective underworld where it rests. And I suspect that those authors never know what the price is until they have already, without knowing the bill, paid it in full and given up some part of themselves that they will never see again.

If they knew the price, maybe they wouldn’t do it. That’s the difference between a deal with the devil and a deal with genius. When you deal with the devil, you know the price up front. When you deal with genius, you don’t. Maybe that’s why Orpheus didn’t manage to get Eurydice out of the underworld, after all. Maybe that’s why we have so few people who can truly bear the title of genius. They walk all the way out of the underworld before they look back, like Orpheus failed to do. They make a deal with the collective genius, and they don’t check the bill until the deed is done.

Quotes and Notes is a monthly craft essay series by Steven Wingate. Steven teaches at the University of Colorado. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008.

Quotes and Notes is a monthly craft essay series by Steven Wingate. Steven teaches at the University of Colorado. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008.